Carbon Labeling Is Coming For Your Food: Here’s What You Need To Know

6 Mins Read

As companies race to net zero goals and consumers demand more transparency about the products they buy, carbon labels will become a necessity, particularly on supermarket shelves. But do they work? And how should they be designed? Here’s what you need to know.

Note: in this article, we use ‘carbon labeling’ and ‘carbon labels’ as umbrella terms for a whole host of labels that communicate some form of data around carbon emissions, greenhouse gas emissions, and climate-related metrics, as this is now common practice. But for accuracy purposes, it is worth underlining climate labels and carbon labels are not the same things; a climate label is more holistic and includes more metrics than a carbon label, which tends to only focus on carbon emissions.

Just like nutritional information helps grocery shoppers make a more informed decision about the food products they are putting in their cart, carbon labels provide insight into carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions of food items.

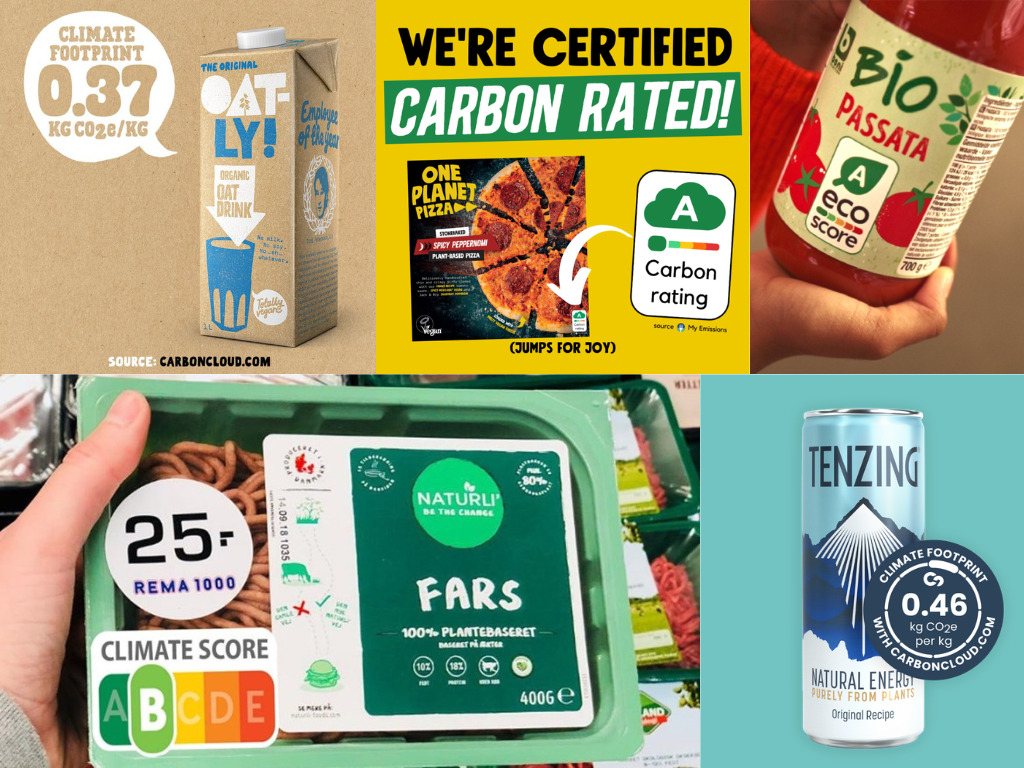

While there are carbon labels that tell about an emissions reduction commitment or that a product has achieved carbon neutrality (usually via the purchase of carbon credits or carbon offsetting), the most common carbon labels show carbon footprint data. In other words, these labels give an estimate of the carbon footprint of a product, i.e. the greenhouse gas emissions associated with a product from its creation to disposal, using either a simple stoplight system for comparison with other products or by displaying its carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in terms of grams/kilograms. Some labels provide both.

There are different types of labels and ways companies communicate their carbon footprints, as you can see from the examples in the above image.

There are so many reasons why we need carbon labeling on food products, not least of which is our food system needs to change and consumer behavior along with it. As we navigate the effects of a global climate crisis, more transparency around the climate cost of the products consumers interact with is needed. Carbon labeling is going to be an important tool in our transparency arsenal. They are necessary, and offer huge potential as a way to engage with end consumers and educated them about major environmental concepts. Food businesses cannot achieve their net zero without assessing the carbon footprints of their supply chains and end products, and eventually, it’s likely regulation will require companies to publish this data publicly. But carbon labeling as a concept faces a host of challenges including a lack of standardization, a need for better and more clear design and more policy support.

Still, it’s hard to imagine a future that will not include more carbon labeling at the supermarket. Below, we dive into what you need to know.

1) The majority of consumers actively want carbon labeling

Multiple studies have shown that most consumers want carbon labeling.

In a survey of over 10,000 people by Carbon Trust from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the US, over two-thirds supported carbon labeling on products.

A 2022 report commissioned by energy drink brand TENZING, found that younger British shoppers want to make planet-forward purchases and feel misinformed/are unclear about the environmental impact of their food choices.

2) The science is clear: carbon labeling on food products works

On the whole, researchers agree, carbon and climate footprint labels are successful at getting consumers to consider the environmental impact of their choices, which is exactly what they are meant to do. In fact, many consumers underestimate the greenhouse gas emissions cost of the foods they buy.

Research published in the March 2018 peer-reviewed Journal of Cleaner Production showed that the presence of a carbon label makes consumers more likely to buy a product. In addition, European shoppers surveyed were willing to pay a price premium of 20% for a product.

A 2017 study concurred: “Our results show that the presence of a carbon label on a product increases the purchase probability and that consumers are willing to pay a (small) price premium for a carbon label.”

In Carbon Trust’s 2020 survey, consumers said that they were “more likely to think positively about a brand that could demonstrate it had lowered the carbon footprint of its products.”

In the TENZING study, participants said carbon labels would help change their consumer behaviour.

3) Carbon labels are inconsistent and confusing

While carbon labels motivate consumers and many want to see more of them, the average consumer may not have the carbon literacy to assess the carbon labels they are shown. They don’t know enough about the measurements used and what is included in the calculation.

According to research, 81 percent of participants found the understanding and comparison of carbon footprint information difficult and confusing (Gadema and Oglethorpe, 2011).

What goes into a carbon footprint? Or is it climate footprint? And what about LCAs? (Life Cycle Assessment)? What does 1 kg / CO2 kg even mean? Or is it CO2e (a blended metric that also accounts for methane and nitrous oxide)?

While it’s encouraging to see brands using company blogs to be more transparent about- see Oatly’s detailed overview here– a busy grocery shopper is unlikely to spend 10 minutes reading a long-form website post while working through a long shopping list in the middle of a crowded store.

Consumer advocacy groups must work together with brands and governments to help create standardization.

4) A universal carbon footprint framework is needed urgently

There are now dozens, if not hundreds, of companies that promise to help brands ad corporates calculate their carbon footprint. But these all work differently.

Different food brands use different carbon audit tools and software. Each of those may use different data sets for their calculations and different variables in their equations. Some labels are based on LCA methodology, but LCAs don’t tend to include information about pesticides, soil health, biodiversity ad animal welfare.

We desperately need a standardized food-specific carbon labeling framework, ideally a global one but at least national efforts.

Some countries are committed to working o this. Denmark wants to be the first country in the world to have a state-wide climate label and the government has put aside DKK 9 million to design one.

In Europe, the Eco-Score which was launched in 2021 by a group of 10 French groups including ECO2 Initiative and Open Food Facts, is gaining traction. The front-of-pack label gives food products a color-coded score between A (good) and E (not so good). The Eco-Score is the climate equivalent of the Nutri-Score, which appears on millions of European foods.

5) Simple, recognizable labels like the traffic light design work best

How should carbon labels be designed? This is an important question. Researchers have tested various designs and formats and agree on a few points.

The labels need to be clear, visually appealing and highlight tangible benefits to the consumer.

Clever Cabon, a platform whose mission is to increase consumer climate literacy, lists three main carbon label formats:

- Graded: label includes some form of grade such as A, B, or C, or low, medium, high

- Footprint: label includes the numerical footprint value of the product

- Footprint with Details: label includes the numerical footprint value of the product with the breakdown of the footprint in the lifecycle (materials, production, transport, packaging, use, end of life, etc)

The graded/traffic light approach seems be one of the most promising options. As per a 2021 study published in Journal of Cleaner Production, “when carbon footprint labels are re-designed using consumers friendly symbols (e.g., traffic light colours), consumers’ understanding significantly increases”.

A 2016 Danish study came to the same conclusion. “Using colors to indicate relative carbon footprint significantly increases carbon label effectiveness. Hence, a carbon footprint label is more effective if it uses traffic light colors to communicate the product’s relative performance.”

6) Carbon labels need to provide context and benchmarking

Another part of carbon literacy that consumers need help with is how to assess the stat they are shown on a food packaging label in the larger context of their lives, i.e.

how the carbon footprint shown compares to the footprint of other daily actions, such as driving your car, buying new clothes or using plastic.

Ideally, labels need to provide some benchmarking and equivalency data for a consumer to easily compare different purchase choices and be able to better understand the carbon cost of a food product in relation to a piece of clothing or a makeup product, as well as a more general understanding of food production’s role in the global emissions budget compared to other industries.