3 Mins Read

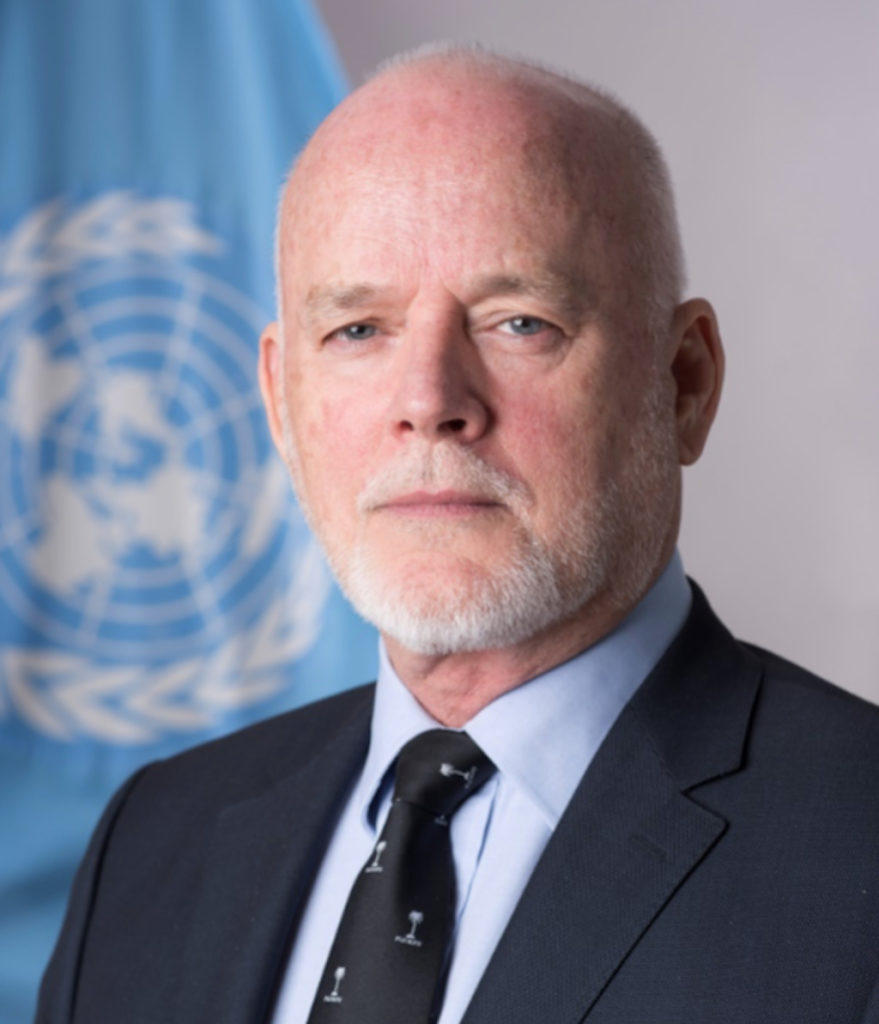

The United Nations secretary-general’s special envoy for the oceans, Peter Thomson, has urged states to put an end to fisheries subsidies. Describing the $22 billion in funding to overfishing operations as “madness”, Thomson said it is now time for countries to “do the right thing by the ocean”.

At a recent virtual webinar hosted by Friends of Ocean Action (FOA), Thomson said countries must end the “environmental and economic madness” of funding fishing operations. Every year, countries funnel $22 billion to fisheries that are driving the unsustainable depletion of ocean fish stocks.

Right now, we are stripping the ocean at a dizzying rate. One-third of the world’s fish stocks are overfished, according to U.N. estimates. 90% of fish are already fully exploited, overexploited, or depleted.

‘Do the right thing by the ocean’

U.N. member states have so far been unable to reach a global deal. But Thomson is hopeful. “We have waited a long time, but we have faith that this is the year,” he said during the event.

Thomson added that we are currently at a “critical stage” in global negotiations. Trade ministers from around the world are set to convene on July 15 to bring talks to a close.

“We should all be urging our respective member states to do the right thing by the ocean,” said Thomson, who is also the co-chair of the FOA.

Subsidies can be redirected to protect the ocean, such as marine conservation projects or helping coastal communities with climate mitigation.

Overfishing: social and economic injustice

Thomson’s comments urging for an end to the “madness” of fisheries subsidies aren’t new. He has previously targeted both the environmental consequences and the related socioeconomic injustices from commercial fishing.

On World Fisheries Day (November 21) last year, he said these public funds subsidising overfishing is “putting food and job security at risk around the world.”

“Since the great majority of these subsidies goes to industrial fishing fleets, the very survival of countless coastal communities relying on small-scale artisanal fishing is being jeopardised,” he wrote.

Awareness of the harms of the fishing industry has grown in recent months, especially after the release of Seaspiracy. The controversial Netflix documentary highlighted the industry’s role in plastic pollution, destruction of marine ecosystems and human rights abuses.

It called for consumers to take action by switching to sustainable vegan alternatives on the market. Examples include New Wave Foods’ algae-based shrimp or Good Catch’s legume-based tuna.

World’s biggest overfishing funders

According to a study by Oceana, the biggest financiers of overfishing operations are China, Japan, Korea, Russia, the U.S., and Thailand. Taiwan, Spain, Indonesia, and Norway also made the list of top 10 countries.

Together, these 10 countries have spent an estimated $15.4 billion on harmful fisheries, of which $5.4 billion went to operations in the waters of other nations. Many of these operate in the oceans of the least developed countries (LDCs) and high seas.

An international agreement to end fisheries subsidies would end this “moral hazard,” according to Thomson.

“Developed countries, exploiting the marine resources of developing countries, to the detriment of the latter’s domestic fisheries and tourism officials,” he said. “The list goes on and that is why we have to end this madness.”

Lead image courtesy of Unsplash.