6 Mins Read

Palm oil is the world’s most versatile vegetable oil. It is present in virtually every consumer product category, from beauty and cosmetics to food and the very material used to construct home furniture. However, global demand for the palm fruit’s oil – and the many ingredients derived from palm oil – is keeping the forests in Indonesia and wider Southeast Asia burning. Trees, the planet’s emissions-absorbing tool key to curbing ever-rising temperatures, are being slashed for more palm oil production. Despite consumers pointing their fingers at corporate giants who have fuelled the crisis, we’re still buying the products that contribute to deforestation – knowingly and unknowingly, thanks to the lack of monitoring and sanctioning to back up anti-deforestation regulations, and the truth behind unlisted palm oil ingredients. If there is anything we know, companies respond to money. So for those who care and are willing to take meaningful action, the question goes beyond should we, but can we realistically boycott all palm oil products?

When palm oil was first discovered and then seized on by the commercial world for its incredibly adaptable qualities – from making lip glosses shiny and smooth to keeping soaps foamy and cookies crispy – it exploded all over the world. Today, 3 billion people across 150 countries use products containing palm oil – translating to an average of 8 kilograms of palm oil consumed by each person annually.

This incredible demand for palm oil led producers to burn down more forests to plant more trees that grew palm fruit that the oil could be extracted from. With many of the world’s palm oil plantations located in Asia – 90% of palm oil trees are grown on just a few islands in Indonesia and Malaysia – these two countries’ biodiverse tropical forests have been born the brunt of destruction over the years.

Not only has this lead to mass deforestation, spewing dark smoke is released into the atmosphere constantly, the devastation in terms of greenhouse gases is two-fold: on one hand, the burning of forests is adding greenhouse gases that make the earth warmer, and on the other, the removal of the very living trees that should be absorbing these emissions, not to mention sustain the habitat that endangered animals live and depend on. And this is before touching on the human cost involved: the palm oil industry has been mired in serious allegations of labour and human rights abuses over the years.

As reports about the environmental and social devastation the industry is accountable for continued circulating, much of it thanks to the work of environmental activist organisations such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, business leaders were more willing to wield to the demands of an awakened consumer base. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) were able to convince a small group of producers, manufacturers and retailers to establish a Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which later committed some of the biggest palm oil purchasing corporations such as Unilever, Nestlé, Mondelez and P&G – conglomerates that own hundreds of major commercial brands such as Cadbury’s, KitKats, Axe and Dove.

Despite the fact that activism has led to stricter regulations over palm oil production and its association with deforestation in Southeast Asia, the region’s precious forests are still burning. In August, while mainstream media and online channels were infuriated over the Amazonian rainforest wildfires, we reported on the fires that engulfed the Indonesian forests, which raged on for months and plunged the region into a severe haze, affecting as many as 30 million in the region. According to the Indonesian Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB), 99% of the fires have been deliberately set by palm plantation farmers to meet the continued global demand for palm oil and other over-consumed commodities.

Ultimately, the RSPO-certification that is supposed to act as a watchdog for sustainable palm oil production, failed. There was initial hope that the oversight offered by the body could yield real changes, especially with the grudging agreement of major corporations. But the most recent Greenpeace report seriously cast doubt on the efficacy of these regulations: all four aforementioned multinational consumer goods companies have continued their affiliation with palm oil suppliers that have been linked to forest burning. There clearly remains a huge gap between corporate commitments and the reality of supply chain operations.

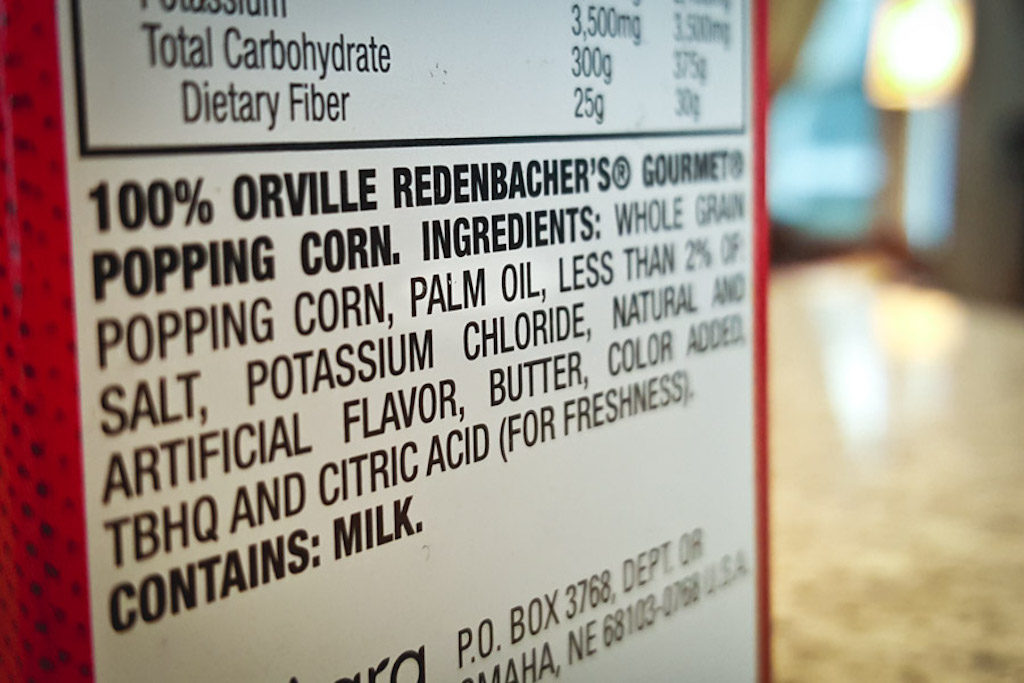

As consumers, making responsible decisions could not be more difficult. Firstly, it turns out that RSPO-certified products might not really only contain palm oil or derivative ingredients that have been sustainably produced. Secondly, meaningful actions – such as boycotting all palm oil containing products – on the part of consumers is further complicated by the fact that most of the time, it is not even clear which FMCG products contain palm oil. According to an investigative reporting by Palm Oil Investigations, more than 200 everyday ingredients in food, home and personal care goods contain palm oil, but only 10% of them have the word “palm” listed in print.

Even as the backlash against the palm oil industry prompted some supermarkets to pledge to remove all products that list “palm oil” as an ingredient from retail, the fact remains that palm oil and its derived ingredients can simply hide under other pseudonyms. It has become so ubiquitous as an ingredient that it would be virtually impossible to remove all products that contained the versatile oil. It isn’t just in junk food, it is fractionated and used in lotions, makeup, and even adhesives. As the Guardian’s Paul Tullis writes, it would require “an almost supernatural level of consumer consciousness” to adequately determine which products contain palm oil, and which didn’t, to launch a successful boycott campaign.

Calling for an industry-wide structural shift away from palm oil in favour of other vegetable oils might not be the best solution either, for our wallets or for the planet. Oil palms produce 4 to 10 times more oil per acre than coconut, soy or canola, meaning that these other alternatives would require even more land and deforestation to produce to meet current consumer demand.

There is a glimmer of hope, however, and the answer seems to lie in whether we as individual consumers are willing to fundamentally change our lifestyles. Embracing a zero-waste lifestyle might just be a solution. And by that, we mean doing (much) more than just consuming fewer processed goods and avoiding factory manufactured products that are the common culprits for containing deforestation-associated ingredients. Going above and beyond to avoid commercial products, especially those that can be bought packaging-free or made ourselves at home, could be the only chance we have. Or at least within the near future, until a new alternative presents itself before our planet is engulfed in climate catastrophe.

Lead image courtesy of WWF Indonesia.