Efficient Irrigation & Dietary Shifts the Top Ways to Prevent Water Stress For One Billion Asians

Asia’s water insecurity is escalating, threatening further economic and social risks; adopting measures like better irrigation systems and sustainable diets can avert this crisis.

The world’s largest continent is home to 60% of its population and produces more than half of all crops, but its food security is facing a critical threat.

Asia’s already alarming water crisis is set to deepen three times more quickly over the next decade, with a combination of climate change plunging an additional billion people into water stress. With agriculture taking up 80% of the region’s freshwater supply, scarcity will disrupt food production and exacerbate food insecurity.

Action to protect the continent’s food security and maintain a stable water supply “must and can be taken now”, according to the latest Asia Food Challenge report by Oliver Wyman, Rabobank and Temasek.

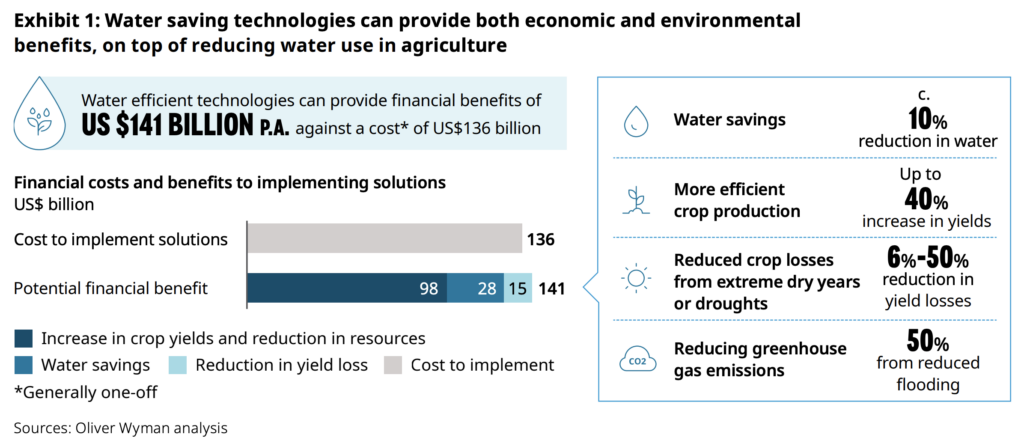

The analysis lays out measures that could save enough water to fill 85 million Olympic-sized swimming pools, creating $141B in combined financial benefits each year.

“Rising water stress is threatening crop yields, livestock health and food security across the region,” said Dirk Jan Kennes, head of Rabobank’s RaboResearch Food & Agribusiness division in Asia. “The good news is that proven technologies and practices already exist to improve water efficiency and reduce usage.”

He added: “By investing in water distribution infrastructure and sustainable farming practices such as precision irrigation and soil management, stakeholders can collectively address the challenge of water stress while enhancing resilience across the entire food system.”

The factors drowning Asia’s water resources

According to the report, Asia’s water crisis is a result of deeply entrenched structural issues. Agricultural production here is dominated by water-thirsty crops like rice, wheat, sugarcane, alfalfa, and cotton – and historical diets and cultural preferences have “locked farmers into practices that extract beyond ecological limits”.

Government subsidies have made such crops economically attractive, but environmentally costly. In India, for instance, free electricity and procurement support have embedded rice paddy cultivation in Punjab, where groundwater is being extracted at over 150% of annual recharge rates now.

Subsidies and financial markets also reward output over efficiency, and water risks remain systemically unpriced. There’s more funding towards water-heavy crops, and water-smart technologies remain underfunded and out of reach for smallholder farmers (who produce nearly 80% of Asia’s food).

Governance gaps make things worse. The report suggests that water policy can be fragmented across government ministries and tiers, with different authorities pursuing their own mandates and neglecting the bigger picture.

Meanwhile, irrigation and drainage networks built in the mid-20th century now suffer from heavy conveyance losses, sedimentation, and inadequate upkeep. Weak monitoring and water accounting mean that few countries can reliably track withdrawals or enforce penalties for overextraction.

Additionally, environmental externalities – like physical water scarcity, climate volatility, and soil or land degradation – exacerbate Asia’s water stress. Groundwater tables are sinking below viable extraction depths, threatening the natural buffer that can protect against surface water shortages, and rivers and reservoirs don’t provide reliable flows to meet agricultural demand anymore.

These effects are intensified by climate volatility, with rainfall more erratic, droughts longer, and flooding events more extreme. Soil and land degradation are further weakening agricultural productivity, with erosion stripping away fertile topsoil and rising salinity reducing plants’ ability to take up water.

How Asia can tackle its water crisis

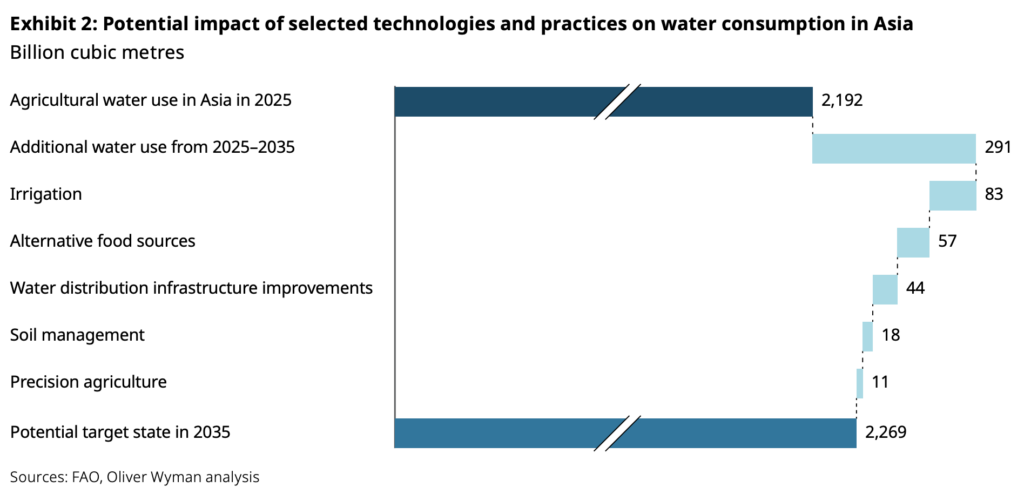

A handful of technologies and initiatives can actually deliver water savings at scale. The single largest opportunity comes from irrigation efficiency – only one in 10 Asian farms use modern systems, versus 21% globally. Even a modest increase to close this gap could save 83 billion cubic metres of water over the next decade.

The second most effective lever is a shift towards alternative food sources and seed innovation. Crops like rice and wheat use up a disproportionately high amount of water, only surpassed by meat products like beef, pork and chicken.

Instead, more efficient plants like millets and sorghum need 60-70% less water on average. And pulses like lentils and chickpeas, which contain 20-25% protein (versus 23-27% of protein from animal sources), require 70-90% less water than meat.

According to the report, replacing just 2% of rice, wheat and maize with water-efficient crops like millets and sorghum, and 2% of conventional meat with cultivated or plant-based proteins could yield another 57 billion cubic metres in water savings.

Aside from these two measures, improving water distribution networks by lining 16% more agricultural canals can save 44 billion cubic metres of water; regenerating soil on 22% of degraded land in Asia can deliver 18 billion cubic metres in savings. Moreover, applying precision farming technologies, like IoT sensors, greenhouses, and controlled environment agriculture, to just under 1% of irrigated land can save 11 billion cubic metres of water.

By adopting these solutions, policymakers and investors can help lower on-farm water use by about 10% – slowing the growth of water stress by 2% – and save a combined 214 billion cubic metres of water by 2035. With greater adoption levels, this could stretch to a further 5-10% reduction.

Implementing these strategies would require a one-off investment of around $136B, delivering annual benefits of $141B. More efficient water and input use can boost crop yields by up to 40% and cut fertiliser 30%, alone producing $98B in added value from higher productivity and lower costs. Further, these measures would cut drought-related yield losses by 6-50%, and halve emissions from reduced flooding.

Still, water solutions only get 1-2% of overall climate tech funding, and most of this capital is concentrated in the West, highlighting an urgent need and opportunity for greater investment in Asia. “Addressing Asia’s water challenges will require directing targeted investment to strengthening the foundations of our water economy,” said Anuj Maheswari, head of agrifood at Temasek.

“By focusing resources on scalable, impactful solutions, we can embed innovation at the heart of the water economy, accelerating adoption and delivering meaningful, lasting benefits across the region,” he added. “Through strong partnerships, we can help ensure water security and resilience for communities across Asia.”