10 Things We Learned About China’s Alternative Protein Ecosystem in 2025

It has been a big year for China’s future food economy – here are the 10 trends that defined the country’s alternative proteins space in 2025.

From regulatory wins and public investment to patent filing and a restaurant boom, China’s alternative protein industry has had a lot going for it in 2025.

The Asian behemoth has been angling to become a global biotech leader, having decisively conquered the green energy and mobility spaces.

People in China have already been eating more protein per capita than Americans since last year, a majority of which comes from plants. As the world’s largest market for meat (accounting for around a third of the world’s supply), its food industry needs faster solutions to decarbonise.

A transition to alternative proteins, whether plant-based, fermentation-derived, or cell-cultivated, can ramp up China’s emissions reduction drive, while also clearing up vast amounts of land.

The country’s reputation as an R&D and biomanufacturing powerhouse, combined with growing support from citizens and the government, outlines its future food potential, as evidenced by this industry’s biggest trends in 2025

1) Plant-based is defying China’s restaurant slump, but challenges remain

Restaurants have always been a tough business, though never more so than after Covid-19. Rising food costs and wages and shifting consumer behaviours meant that 70-80% of Chinese restaurants lost money in 2024. In fact, seven in 10 new eateries failed within three months of opening.

As highlighted by Toronto-based Dao Foods International, a China-focused impact investment firm, meat-free restaurants are bucking the trend. The number of vegetarian establishments has nearly tripled from under 5,000 to over 14,000 in the last five years.

That said, the category still maintains a small share of China’s eight million restaurants, with several challenges and opportunities to grow. Scalability is particularly a big challenge, with over 95% of meatless restaurants having fewer than three locations, in contrast to meat-serving chains that have dozens (or even hundreds) of sites.

2) Health is driving the Chinese vegan market’s growth

It’s well documented that health influences food choices in China more than any other factor, and this is true for consumers young and old.

In a market survey by the China Vegan Society, which kicked off the Veganuary-style V-March campaign this year, 36% of respondents said they choose plant-based diets for health reasons.

Data from Meituan, a Chinese app offering a wide range of lifestyle services, finds that people aged 25-35 make up two-thirds of vegetarian catering orders. And as vegetarianism has grown, the share of consumers under 30 who have embraced the diet has surged by 29% over the last three years.

At the same time, the country’s rapidly ageing population – 310 million (or 22% of the total) were aged 60 or above as of 2024 – is dictating the market shift too. These consumers tend to reduce meat consumption due to digestive issues and cardiovascular concerns. Vegetarian chain Sumanxiang reports that 35% of its diners are 55-plus, highlighting how seniors have also become a core meat-free group.

3) Prices still dictate future food adoption

Still, affordability is a major barrier to the shift towards alternative proteins. Beyond Meat, which has suspended its China operations, is a good example.

Its plant-based beef costs nearly twice as much as conventional beef mince in the country’s supermarkets. Even meat alternatives made by local brands are half as pricey as Beyond Beef. It’s not just beef, either – the company launched pork meatballs in February with a price tag over 10 times that of animal-derived counterparts.

And when you factor in the ubiquity of tofu and seitan in China, the price gap widens even further. “Tofu and traditional alternatives are cheap, widely available, and sold in bulk. Plant-based meats are often significantly more expensive,” Jian Yi, founder and CEO of the China Vegan Society, told Green Queen in June.

As Dao Foods pointed out, low-cost plant-based food can shift perceptions amid consumers hit by the cost-of-living crisis. Vegan buffet restaurants were initially not well-received by consumers, who associated them with religious veganism or low-income citizens and perceived the quality of the food to be poor.

After the economic downturn, vegan buffets priced around ¥30 ($4.25) have gained traction; meat-based versions typically cost around ¥100 ($14.15). The former options, roughly the price of a bubble tea, offer compelling value, and most diners aren’t even vegan.

4) China is going all-in on microbial proteins

Proteins derived from microbial fermentation are having a moment in China. In Angel Yeast, the country is home to the world’s largest producer of yeast protein. It began operating an 11,000-tonne production line earlier this year, with built-in expansion capacity to meet future market growth for yeast protein.

Meanwhile, Fushine Bio is the nation’s largest mycoprotein producer, and has become the recipient of China’s first regulatory green light for these foods. It can churn out 1,200 tonnes of product per year, and an industrial-scale line with an annual capacity of 200,000 tonnes is under construction.

Overseas companies are recognising the potential. Australia’s All G received regulatory clearance to sell its recombinant bovine lactoferrin protein in personal care formulations, supplements, and more in China. It is now working with a local contract manufacturer ahead of a launch in early 2026.

Fusarium venenatum has been identified as a key opportunity to advance China’s alternative protein sector, with a group of leading scientists recognising its ability to “meet the stringent protein quality requirements of high-end markets such as medical nutrition, sports nutrition, and infant formula” in a recent blue paper.

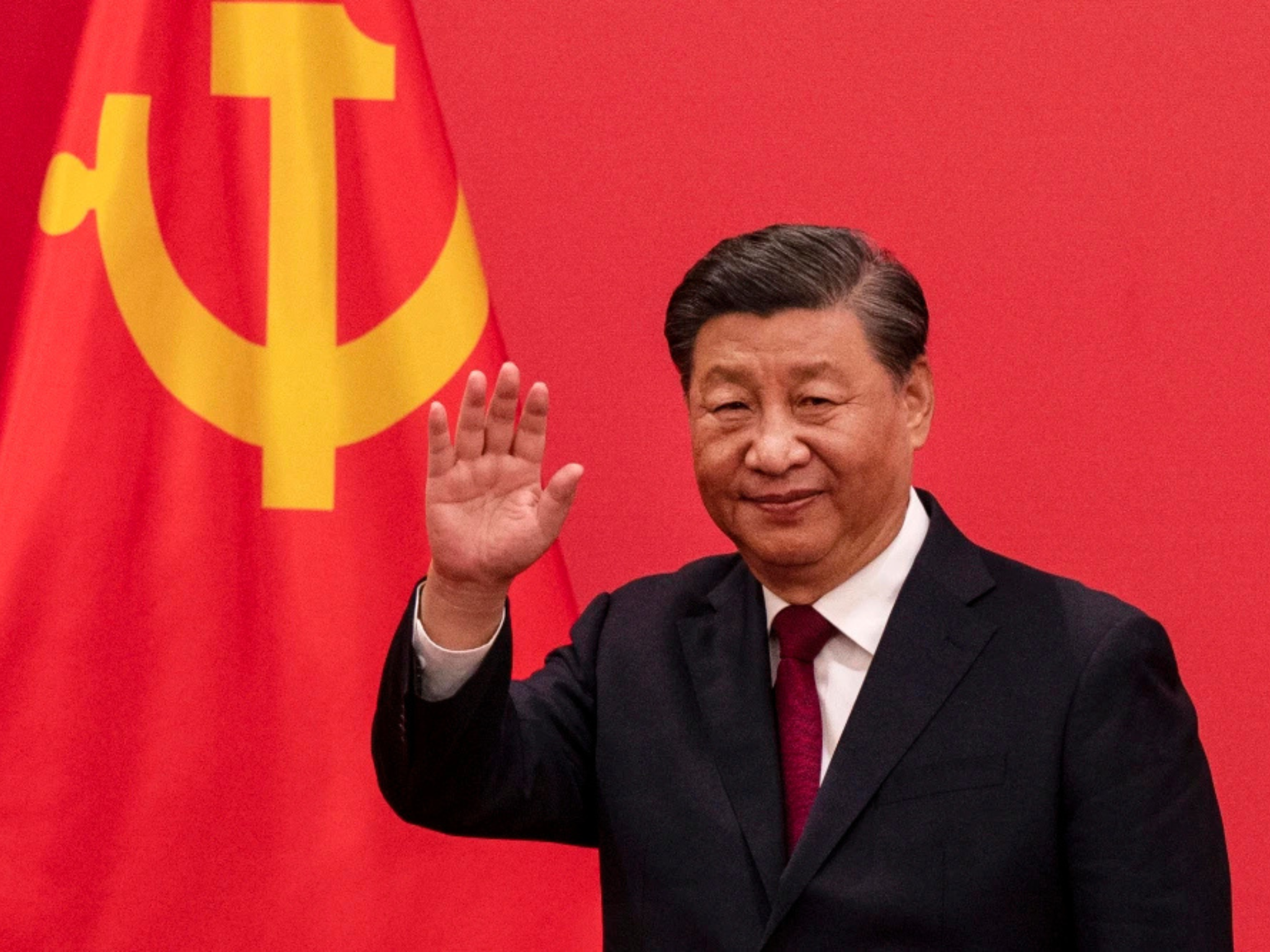

Plus, the government’s current five-year agriculture plan (which runs until the end of the year) encourages research on recombinant proteins and cultivated meat. And President Xi Jinping has previously called for a Grand Food Vision that includes plant-based and microbial protein sources.

5) China’s innovation ecosystem is second to none

The East Asian country’s research prowess is the bedrock of its future food potential. According to the Good Food Institute APAC, of the top 20 all-time patent applicants for cultivated meat, eight are from China. That’s twice as many as Israel, the next on the list.

The number of patent families – collections of applications related to the same invention – is significantly greater from Chinese entities than from other markets (totalling 160). Cultivated pork maker Joes Future Food leads the way in China with 25 applications.

China’s applicants include multiple universities as well, such as Zhejiang University, Jiangnan University, and Ocean University of China. Experts say this indicates “very strong” government interest and an intentionally collaborative approach to build a national cellular agriculture ecosystem.

6) The hospitality sector is leading the protein transition

Though the research and manufacturing sectors are building China’s capacity to produce future foods, it will all be in vain if consumers don’t embrace them. It’s why the hospitality industry is critical, serving as a lever for greater adoption of alternative proteins,

In a scorecard compiled by Lever China, 11 large hotel operators received an A+ rating for their corporate policies on increasing plant-based food offerings. The score reflects public, time-bound targets to make at least 30% of all meals plant-based, or increase the percentage of non-animal foods served per guest by at least 20%.

Among the companies driving the industry’s protein transition are Accor Hotels, Marriott Greater China, Langham Hospitality, IHG Hotels & Resorts, and Dossen Group.

7) Consumers are increasingly open to cultivated meat

As cultivated meat companies ramp up R&D and scale-up efforts, they will be buoyed by the public’s growing acceptance of these proteins. A survey by the APAC Society for Cellular Agriculture (APAC-SCA) found that 77% of people in four tier 1 cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen – are willing to try cultivated meat and seafood.

Moreover, 45% of consumers say they’re likely to replace conventional meat and seafood with cell-cultured versions. There is a need for further education, though, as a third of respondents aren’t familiar with cultivated meat, and of the 63% who have heard of it, just one in 10 knows what the concept means.

Further, China’s consumers need more assurances about the safety of these foods. “As consumers place a strong belief and trust in food safety regulators, unified messages from government stakeholders and industry players would be most effective to provide assurance on health and safety,” Calisa Lim, senior project manager at the APAC-SCA, told Green Queen.

8) Global brands still find it hard to cut through…

Companies that may lead the market in other parts of the world aren’t guaranteed success in China. Oatly’s struggles are well-known, with the company restructuring its market divisions by separating Greater China from the rest of its Asian business.

As alluded to above, Beyond Meat has failed to gain ground, leading the plant-based meat producer to close its China operations and lay off 20 employees. Concerns around ultra-processing, high prices, and unsatisfactory taste all contributed to its middling performance in this market.

International firms need to home in on localised flavours and preferences, and they need to do so at an affordable price point. Beyond Meat did the former with its pork meatballs, but not the latter. In general, overseas brands find it difficult to break through the familiarity of established local companies.

For instance, Japanese food giant Glico (the producer of Pocky) has been a household name in China for over a century. And since launching its almond milk in 2021, the company now sells more of it than any other company in the category, thanks to a deeply localised marketing strategy leveraging identity, self-expression, and social media.

9) …but homegrown brands are going global

The flip side of this issue is, Chinese companies are increasingly looking outwards for success, thanks in no small part to the impact of Donald Trump’s tariffs on the country. They have pushed companies to relocate manufacturing to other countries and enter the market with their own consumer brands.

They’ve spotted it as an opportunity to drive higher margins, brand value, and market resilience in international markets, according to Dao Foods. The shift is also in response to expanding industrial overcapacity and a slowdown in domestic consumption.

Chinese plant protein brand Starfield, for instance, showcased a diverse range of products, including a Poki Salad Bar, vegan bacon strips, and dairy-free cheese, at the 2025 International Food & Drink Event (IFE) in London.

Meanwhile, alternative protein innovator Cellx relocated from Shanghai to San Francisco, pivoting to a licensing model for its cultivated meat platform, and launching a new brand of morel mycelium protein snacks for the US market.

10) The government is going all-in on alternative proteins

Perhaps the most significant future food trend in China is the continued support from the government. Building on its agriculture and bioeconomy plans, top government officials called for a deeper integration of strategic emerging industries (which included biomanufacturing) at this year’s Two Sessions summit.

This came shortly after the agriculture ministry highlighted the safety and nutritional efficacy of alternative proteins as a key priority. In addition, No. 1 Central Document (which signals China’s top goals for the year) underscored the importance of protein diversification, including efforts “to explore novel food resources”.

The policy support is translating into investment, too. China’s first alternative protein innovation centre was opened in Beijing in January, fuelled by an $11M investment from public and private investors to develop novel foods like cultivated meat.

And in the Guangdong province, China’s most populous region, local officials are planning to build a biomanufacturing hub to pioneer tech breakthroughs in plant-based, microbial, and cultivated proteins.