8 Mins Read

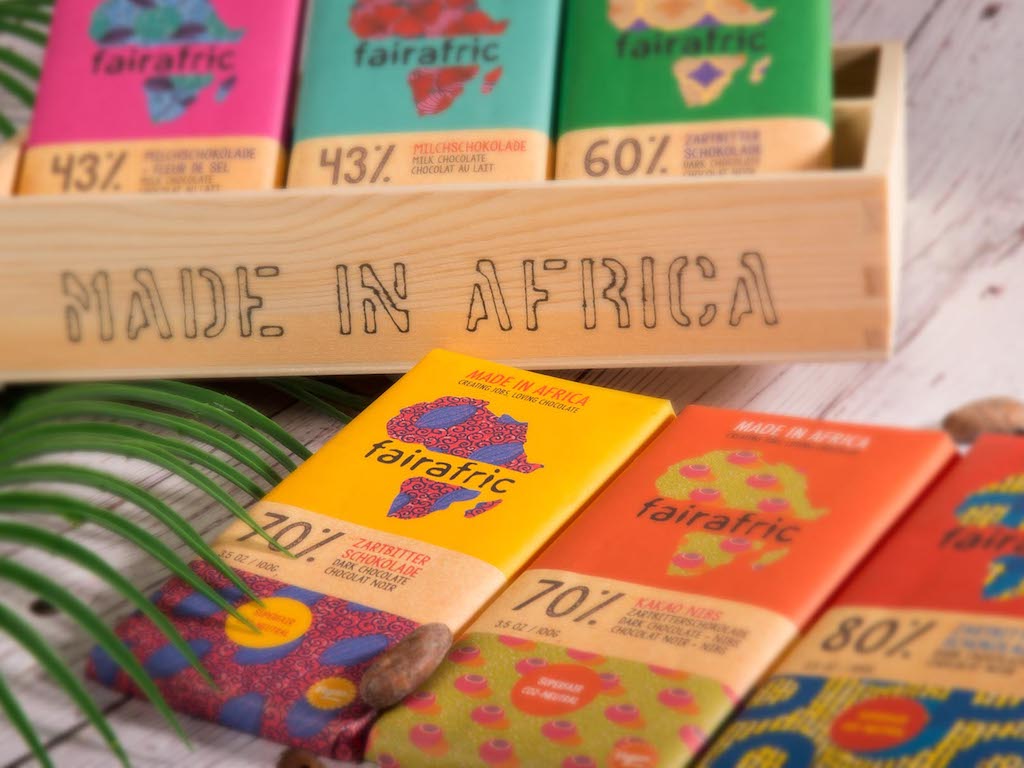

In 2016, Hendrik Reimers founded Fairafric, a social enterprise that brings delicious organic chocolate bars to the world, sourced, produced and wrapped in Ghana. Unlike many Fairtrade certified brands, where the most impact isn’t really delivered to the cooperatives, producers and workers at the start of the value chain, entire value creation of every single Fairafric bar takes place in Ghana, increasing local job opportunities, income and with it, access to education and healthcare. In this interview, we speak to Hendrik all about the misconceptions surrounding Fairtrade, how his company ensures real social impact and the exciting plans ahead for Fairafric to better the lives of people while minimising harms to the planet.

GQ: Tell us a bit about your journey that led up to the founding of Fairafric. How did the idea come about?

HR: I’ve been in Development Economics for a very long time and during the time I spent travelling, I realised that most of the solutions that we know in the West weren’t really making a difference on the ground in developing countries. The problem is the structure of these economies, which are heavily dependent upon importing finished goods and exporting raw materials. I suppose I got that “aha!” moment when I was spending time on a coffee farm. After showing me around the farm, the farmers offered me coffee taken from the green beans that they grew, roasted them on open fire and ground them manually before pouring a cup of delicious fresh coffee. I thought – wow, they need to be selling the finished product, not the beans! But this isn’t an available option for somebody who doesn’t own a bank account or a passport, has never travelled and will never, most likely. That’s when I realised that we need to build a bridge and connect these people to other markets in the world.

GQ: What were some of the main challenges that you had to overcome to build an ethical chocolate brand?

HR: If you build a new chocolate factory in Europe, you already have all the suppliers, skilled workers, people who can help with cooling technology, the heating and so on. That’s not present in most countries in Africa, which means that most of the time, we need to bring in our own solutions. So that requires planning way ahead of time, as the equipment isn’t readily available, considering all sorts of factors such as wastewater treatment, electricity and water supply. Basically, all these things that we take for granted in the developed world had to be solved ourselves when we began to build our brand in Ghana.

GQ: In a previous conversation, you mentioned Fairtrade as a format doesn’t work. Can you share more about this? Why do programs like Fairtrade, the Rainforest Alliance and UTZ fail to truly move farmers out of poverty and “decolonise” chocolate?

HR: Definitely. At the core of the problem is trying to solve widespread poverty present across West Africa and other raw material exporting countries, where people live as smallholder farmers in communities. What Fairtrade is looking at is to pay these farmers more, but it doesn’t solve the problem of their continued poverty as smallholder farmers. On the contrary, once a generation moves on and land is being inherited and split among the children, the size of the farms themselves is decreasing all the time. So what countries need to do is to move away from smallholder farming towards adding value to resources locally and to make products themselves. That’s the approach that we’re taking with our brand, and that’s what we think is a better structure to eradicate poverty and to kick the very system that had created the problem in the first place out.

What Fairtrade is looking at is to pay these farmers more, but it doesn’t solve the problem of their continued poverty as smallholder farmers.

Hendrik Reimers, Fairafric

GQ: Given how such schemes may not always deliver the intended impact for farmers and workers in developing countries, what are some ways for consumers to make the most ethical and responsible decisions possible when we are essentially shopping “blind” most of the time?

HR: That’s a very good question. Consumers need to spend time researching brands that are really making a difference and aren’t just labelling their products “fair”. Obviously, I’m an expert in chocolate, and there are a few smaller brands that also take the same approach as us, where the chocolate is produced where it is grown, providing not only qualified labour and jobs in these countries but with it the supplying industries that will enable other businesses to enjoy these services as well. So it’s about figuring out which brands are making a real difference, and I’m always encouraging people to spend a little more time before they make purchasing decisions, whether it is the big ones or small ones such as our daily necessities, be it chocolate, coffee and tea that we spend our money on the regular.

GQ: Why is artisanal chocolate so popular now? What do you think has driven this explosion? Would you say brands like the Mast Brothers in Brooklyn played a large role?

HR: This is a big question. Europe is a bit different than the U.S. and I can’t really speak for the U.S. market. I think in Europe, there is a market that is moving towards sustainability and conscious consumerism, where people are really looking into what brands are doing. This doesn’t just apply to chocolate, but also other products such as craft beer. Because information flows better nowadays, we can get a much better glimpse into what businesses are doing. On top of that, it is also much more affordable to start a brand. Here in Europe, you have co-packing, where small brands can manufacture together at a cost and rate that is similar to the big brands, and we have the option to set up an online shop. So it’s really the cheapest it has ever been to start a new brand, and it’s certainly playing into the trend of new indie chocolate and other indie product categories.

GQ: Should artisanal chocolate cost as much as it does?

HR: From my perspective, we’re trying to keep as big a share of the retail price as possible in the cocoa growing area. So for us, that means producing the whole bar until it is boxed and wrapped in Ghana, which then means we hire our designers from Ghana and we source as much as we can on the continent as possible. That’s a promise we make for our customers and we are transparent about what part of the eventual retail price reaches the people we think it should reach.

I’m always encouraging people to spend a little more time before they make purchasing decisions, whether it is the big ones or small ones such as our daily necessities, be it chocolate, coffee and tea that we spend our money on the regular.

Hendrik Reimers, Fairafric

Some other artisan chocolate makers, such as those in the U.S. and Europe, a lot of that labour cost remains in the U.S. and Europe and these brands cannot be as transparent about their supply chains. Certainly, not as much of the retail price ends up reaching the people who have grown the cocoa for the chocolate. It’s simply a different business model to ours. Whether it’s worth the price? I’d say that it still is because you have to motivate the right people to produce artisanal quality products. But for us, it’s about bringing as much of that cost to Ghana, that’s our goal and consumers are able to know that as much of what they’re paying is going where you’d like it to go.

GQ: Is bean to bar chocolate really a superior product? Assuming you have tasted beans from all over – are there major taste profile differences between Latin American, Asian and African beans?

HR: It’s definitely up to everyone’s own taste, and I enjoy a great bar from many different destinations where you can get outstanding beans to make fantastic chocolate with. But many of these beans aren’t produced in quantities that would allow large-scale production, and it would be a waste to mix them with other beans. So it makes a lot of sense to take the beans as they are and work with them, and it’s definitely worth and associated with a higher cost, especially in sourcing, and farmers do get paid more for their higher quality beans. But we ourselves are looking at a different angle. Our goal is to create as many jobs as possible in Ghana and it’s hard to do that with small-scale production.

GQ: We know that Fairafric is currently working on building its new solar-powered chocolate factory in Suhum, Ghana. How important is your brand and your product’s environmental footprint?

HR: Yes, this is something that is at our hearts and obviously extremely important. If we could, we wouldn’t have any negative impact on the environment at all. But of course, it’s impossible if you’re trying to make any product. That’s why we try to keep it at a minimum by not only offsetting everything but also reducing our impact by using solar power.

GQ: When will Fairafric be available in Asia?

HR: Once consumers are demanding enough, that’s certainly something we would like to look at! We have to consider many things, transportation costs, for instance, especially since chocolate is a temperature sensitive product. If anyone happens to read this and wants to distribute for us then please do reach out.

GQ: What are some of your favorite chocolate brands, other than Fairafric of course?

HR: I have to say Claudio Corallo. He has the best beans in the world in terms of the lack of bitterness. It’s an extremely interesting product but very hard to get by and very costly. If people really want to try something different, they should try Claudio Corallo.

GQ: And of course, our final question – team rice or team noodles?

HR: I guess I have to be team rice!

All photos and images courtesy of Fairafric.