Beluga vs. Burger: Price Parity and Scalability Won’t Stop Cultivated Luxury Products From Reaching Commercial Viability

By: Prof. Dr. Muriel Vernon, Dr. Sundar Pattabiraman and Henri Kunz

Recently, two Techno Economic Analyses (TEAs) on the subject of (commodity) cultivated meat have been hotly debated. More specifically, the critical cost reduction necessary for its commercial viability, with both TEAs showing that cultivated meat may have a long way to go before it can be successfully and affordably mass-produced. Achieving price parity and scalability with conventionally produced meat are two of the major obstacles when it comes to the commercialization of cultivated meat. However, a laser focus on mass availability could be a detriment to the growing sector of cellular agriculture sector cultivated food and material alternatives that offer solutions for all socio economic tastes, and a wide range of use cases are key to the continued success of the industry. Below we explore this argument more fully.

In the first TEA, by Humbird (2021), Humbird is mostly concerned about contamination risks that would limit the scalability of cultivated meat. He also suggests using Alternating Tangential Flow (ATF) filtration membranes for cell separation in perfusion, which is incredibly expensive-10% of the cost in his optimistic scenario. It’s worth noting that ATF and other membranes are the standard separation method for biopharma perfusion right now, but there are potentially better methods out there. Systems like acoustic wave settling or hydroclones could be significantly cheaper – see Gränicher et al (2020).

In the second by Rinser et al (2020), the researchers point out that profitability is a key question with respect to cultivated meat production. They are also concerned about the issue of sterility that might only be solved by single-use equipment, and even then, the cost of maintaining biopharma-level air quality is considerably high.

In our view, single-use equipment, which can be pre-assembled and sterilized, could allow for production plants that don’t maintain strict sterility, saving on capital and operational costs. Of course, this procedure is not standard right now.

The average cell density or cell mass a bioreactor can hold is also based on particular cell lines*, whose doubling or differentiation time doesn’t necessarily apply to others. In other words, the research is based on what has been done before, not necessarily what can be done, an important distinction.

Neither of the TEAs provides useful suggestions on how to beat the amino acid prices of the fermentation industry, nor how to design bioreactor systems that can reduce the costs of contamination at scale.

Further, neither TEA compares alternatives to the cultivated meat strategy, such as plant-based meat, or fermented novel foods -see Curtain and Grafenauer (2019) and Rubio et al (2020).

The TEAs don’t discuss in detail the recycling of micro-nutrients and the recycling of macro-nutrients, which could also be possible, though admittedly they need more research and dedicated studies.

Nor do they discuss FBS (fetal bovine serum) recycling, or what the cost-reduction gains would be if FBS isn’t used. There are various research articles published that demonstrate that it’s feasible to bypass the use of FBS to grow cells- see Scholefield and Schuller (2014), Van der Valk et al (2010), Andreassen et al (2020). One as of yet unpublished and highly anticipated ongoing study refers to an animal-free growth media for fish cells that is expected to be disseminated by mid-2022.

Lastly, the average cell density- a.k.a the cell mass a bioreactor is able to hold, used in these studies- is based on CHO cell lines (Chinese -Hamster -Ovary), which are arbitrary cell lines, whereas the doubling or differentiation time doesn’t completely apply to novel food applications in cellular agriculture.

Luxury Products As A Path Forward For Cellular Agriculture

It’s important to discuss socioeconomic considerations with regards to the extensive discussion on price parity of commodity cultivated products such as chicken and veal meats. In the introduction to their study ‘Eating for Taste and Eating for Change: Ethical Consumption as a High Status Practice by Kennedy et al (2018)’, the authors write that “contemporary food consumption patterns are complex,[…], ethical consumption options are proliferating, and casual foods like hamburgers can gain high-status cultural cachet.” They then ask: “If high socioeconomic status (SES) people eat burgers, and shoppers from various income brackets purchase dolphin-friendly canned tuna, how are we to understand the relationship between class, cultural capital and ethical consumption?” One of their conclusions that can be drawn is that ethical food consumption seems to be associated “with greater occupational prestige and education”.

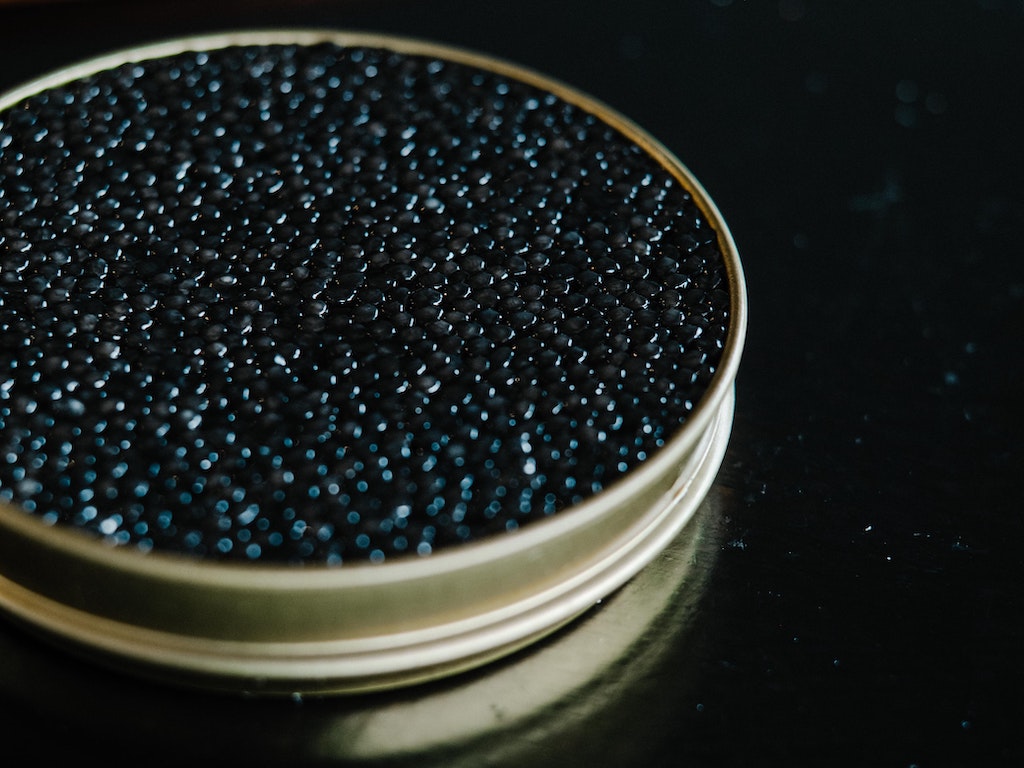

While the focus of the aforementioned TEA analyses is on producing commoditized everyday meats produced by cellular agriculture, such as beef burger patties or chicken nuggets, we believe smaller-scale luxury foods and clothing materials are better candidates as the first cultivated products that would usher in this new era of bio-identical sustainability. Indeed, Rinser specifically mentions “there may be opportunity for viable competition in the specialty foods markets, where ACBM [Animal Cell Based Meat] costs compare more favorably to such items as almas beluga caviar (USD 10,000/kg), Atlantic bluefin tuna (USD 6500/kg), and foie gras (USD 1232/kg)” (10).

Cultivated biomaterials for animal-based clothing can benefit from the same rationale since high-end leather or fur already top the retail market in terms of pricing without apparent upper limits: after all, the goal is not to cheapen or de-luxurize things that symbolize status distinction, regardless of how people might feel about its very existence.

The call to sustainably innovate invites new players to the commercial viability table: bioengineering companies focused on developing cultivated luxury items such as fur, caviar, foie gras, and lobster, may just be able to evade the two production problems that have plagued the cellag space since its inception: price and scalability. The companies’ products are 100% cruelty-free and environmentally-friendly versions of the most conspicuously consumed luxury products in the world and none of them needs to be produced cheaply or in large quantities.

Cultivated Fur vs. Cultivated Meat

Unlike with cultivated food, consumer don’t need to ‘eat’ cultivated fur or biomaterials so they bypass the cognitive threshold of ingesting. CRISPR technology and oncogenes can be used in cell line development and the product would not have to pass extensive safety testing that is a prerequisite for novel food products. There are many other ancillary benefits: cultivated fur complements global animal conservation efforts, which protect endangered species to maintain biodiversity. From a commercial point of view, it could offer hope and creative outlets for the heavily stigmatized artistry that is fur design. In terms of public health, cultivated fur also helps to safeguards from future zoonotic disease: outbreak concerns have led to millions of fur animals such as minks being culled across Northern Europe.

Cultivated Caviar vs. Cultivated Meat

Another example of niche products that can meet consumer demand without achieving mass consumption nor affordability are luxury fine foods, such as caviar. Cultivated caviar would support conservation efforts of wild sturgeons, which have been red listed by CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) as nearly extinct.

This aligns with the larger global problem of ocean life depletion: from 1961 to 2015, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, global fish consumption grew from 9kg to 20.2kg per capita, and consumption is expected to increase precipitously into the 2030s. But the world cannot produce fish at the pace humanity consumes it. Populations of marine species have halved since 1970, due to overfishing and climate change, and microplastics and mercury contaminate the remaining fish in our oceans. Cultivated caviar production would not require large-scale operating facilities as the specialty food item it will most certainly remain.

Alternatives that offer solutions for all tastes are a key consideration in the burgeoning sector of cultivated animal foods and materials. While price parity may be key for consumer appeal in many cellag categories, the socio-economic purchase behavior of wealthy consumers could become far more elastic if moral dilemmas of hedonistic consumption were redirected to benefit sustainability rather than work against it. This is why we believe that the narrative of sustainability needs to include not only affordability for the masses, but also the ability to cater to vastly diverse cultural tastes. We need to reframe the ‘quit meat to save the planet’ and focus more on finding specific solutions and alternatives for a wide range of use cases.

Clearly, small-scale products like caviar are not feeding a fundamental biological hunger, but rather, a cultivated appetite for culinary pleasure, and why not? Do we really need to eat caviar or wear fur? Of course not. The quest for a richer life has never been about making do with the ordinary things that we need, but about enjoying the extraordinary things that we love. The production roll-out challenge is socio-economic, and not techno-economic in nature, which is precisely why a handful of biotech companies are focusing on the luxury market by taking big sustainability ideas into a small market segment.

Our future customer isn’t the kind of person who consumes caviar and wears fur to achieve a higher social status than the person next to them. They are individuals who are trying to be better than they were before by choosing to consume more ethically and sustainably.

About the authors: Prof Muriel Vernon is a member of the Board of Directors at Geneus Biotech B.V.; Dr. Sundar Pattabiraman is CSO at Geneus Biotech B.V.; and Henri Kunz is the founder of Geneusbiotech, a Dutch-German corporation that owns Magiccaviar and FUROID™️.

*An organism consists of various tissues and each tissue consists of different types of cells exhibiting similar signals. When a single cell is taken out and grown in a lab for cellular agriculture purposes, it’s termed a cell line. Extractions of cell lines are typically performed either by sacrificing the animal or (preferably) saving the animal and obtaining a punch biopsy in a controlled environment. This is performed by veterinarians and regulated via approvals of ethics committees.

Lead image courtesy of Mosa Meat.