5 Mins Read

With the climate crisis climbing to the top of the global agenda, more people are beginning to take notice of the connection between our consumption choices and the carbon footprint it leaves behind. While some questions about the footprint of food can appear to be relatively straightforward, the reality may not always be as simple as it seems, particularly when it comes to buying local food vs. imported food. Which is most sustainable?

For a time, environmentalists have been touting eating locally produced food as one of the best ways to lower your carbon footprint. On the surface, it makes sense – transportation generates one of the largest shares of global greenhouse gas emissions, which makes food that requires travel more carbon-intensive.

Although there are a multitude of benefits attached to local agriculture, such as supporting biodiversity, providing jobs and a bulwark against food insecurity – especially in Hong Kong where we now produce a mere 2% of our vegetable supply compared to 50% in the 1960s – we ought to be cautious about sweeping statements about the sustainability of local foods. In reality, the impact of food extends far beyond transportation, which represents only a final fraction of the carbon budget in the entire supply chain.

Recent research has shown that if we take into account everything from land use, deforestation, methane emissions, resources for animal livestock feed, processing, transport, retail and packaging, paying attention to the type of food you eat is far more effective for lowering your carbon footprint than where it has been produced.

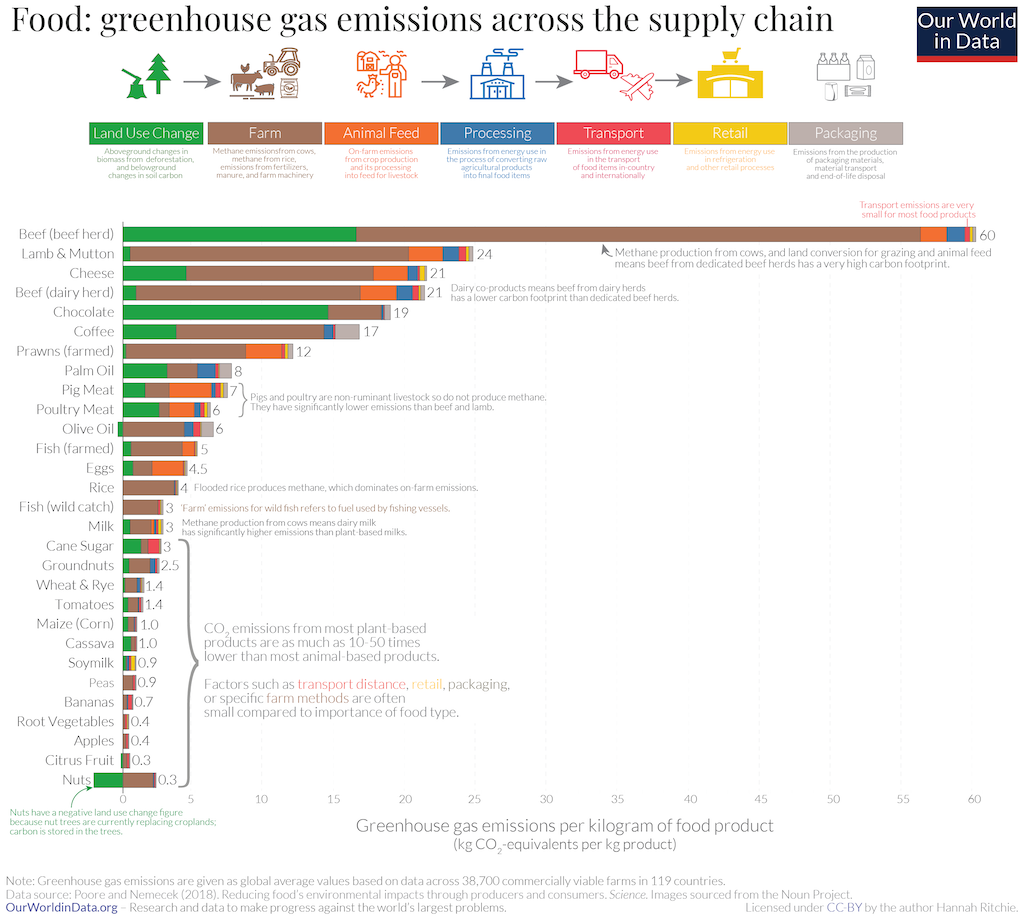

According to a new analysis by Our World In Data published earlier this year, for most foods, it is not the case that transport is responsible for a large share of the final carbon emissions. Using data collected from the most extensive meta-analysis of worldwide food systems to date, the study investigated the different sources of carbon emissions of 29 common food products, from eggs and fish to olive oil and nuts.

It concluded that emissions from the distance our food travels is responsible for only a minuscule fraction of a food’s footprint, and that “what you eat is far more important than where your food travelled from.”

In Our World In Data’s graph, you can see that on average, the travel part of food makes up of less than 10% of a product’s greenhouse gas emissions. The more carbon-intensive part is usually in the production process – agricultural farming methods, amount of land and water wastage, whether a food has contributed to deforestation due to land clearing and methane emissions, in the case of animal livestock rearing. As a rule of thumb, it becomes clear that plant-based food – even if it has been imported – is usually the lower carbon option if compared to locally grown or imported meat products.

“Plant-based foods emit fewer greenhouse gases than meat and dairy, regardless of how they are produced,” the report writes.

While it is always best to choose plant-based, those who do choose to consume meat, dairy or seafood products can opt for less carbon-hefty types, which is determined more so by the way it has been produced than where it comes from. For example, the graph shows that if you have a choice between local prawns or imported fish, then from a carbon perspective, the non-local farmed fish is better, even if it has travelled a certain distance. But remember – this only takes into account the emissions generated from food, and whether you are concerned about the plastic pollution associated with the seafood farming industry or the human rights problems that wild catch is laden with is a different story altogether.

Out of all the types of meat, choosing pork and poultry will have the lowest carbon footprint, regardless of where they have been produced. This is because pigs and chicken do not produce methane when reared, as opposed to beef, lamb and mutton. Given this, if your dinner choice involves either a roasted chicken imported from France or a “low-impact” locally farmed piece of steak, then choosing the chicken is more carbon-friendly.

Again, there are caveats – if animal welfare or health is a priority, then opting to ditch animal meat altogether for plant-based protein sources such as tofu, beans or vegan meat substitutes will be your best bet, both ethically and environmentally, and health-wise too.

Some may be wary about air-freighted fruit and vegetables – and it is a genuine concern, given the enormous amount of emissions that airplanes produce (not too mention the radiation, which no one talks about and on which there is very little research). However, it is worth noting that only 0.16% of food globally is imported by air. These foods are usually those that have a short-shelf life or are produced in countries far away, so if you are concerned about some kinds of carbon intensive produce, then choose seasonal plant foods that are either grown locally or from neighbouring countries. So choosing bananas from the Philippines will likely leave less of a footprint than grabbing strawberries grown in Spain.

Bottom line? Local food is always best if and only if it is plant-based.

Lead image courtesy of Deposit Photos.