8 Mins Read

By: Aaron Kent

Aaron Kent is the founder of Please Drink Sustainably, a Hong Kong-based company providing reusable custom branded cups to businesses switching away from disposables.

Hong Kong’s government has recently completed public consultation for its proposed Plastic Beverage Container Producer Responsibility Scheme – or PPRS for short. Its aim is to reduce the 1.55 billion plastic beverage containers Hong Kong discarded in 2019 and promote domestic plastic recycling, with just 8% currently recycled although some 96% of that is local.

What is a Producer Responsibility Scheme?

A producer responsibility scheme falls under the broader policy area of extended producer responsibility (“EPR”) where producers are given a significant responsibility – financial and/or physical – for the treatment or disposal of post-consumer products. Most often it is a strategy to add all the environmental costs throughout the product’s life cycle to the market price of that product.

What’s in Hong Kong’s PPRS?

Hong Kong’s PPRS is proposing to offer a rebate of HK$0.10 for all plastic beverage containers between 0.1 and 2 litres returned to a network of collection points and reverse vending machines located across the region. Currently, it will be compulsory for drinks retailers to have a return point in any store larger than 200 sqm – i.e., nearly all supermarkets. There are exclusions, namely other forms of beverage packaging (aluminium cans, cartons) and it also excludes containers that are considered plastic dining ware such as bubble tea and takeaway cups (which are filled and sealed immediately prior to sale).

Several green groups have heavily criticised the proposal, from the rebate amount to the model itself. Here are 8 reasons why it looks set to be fall short.

1. A Poor Record On Plastic Bags

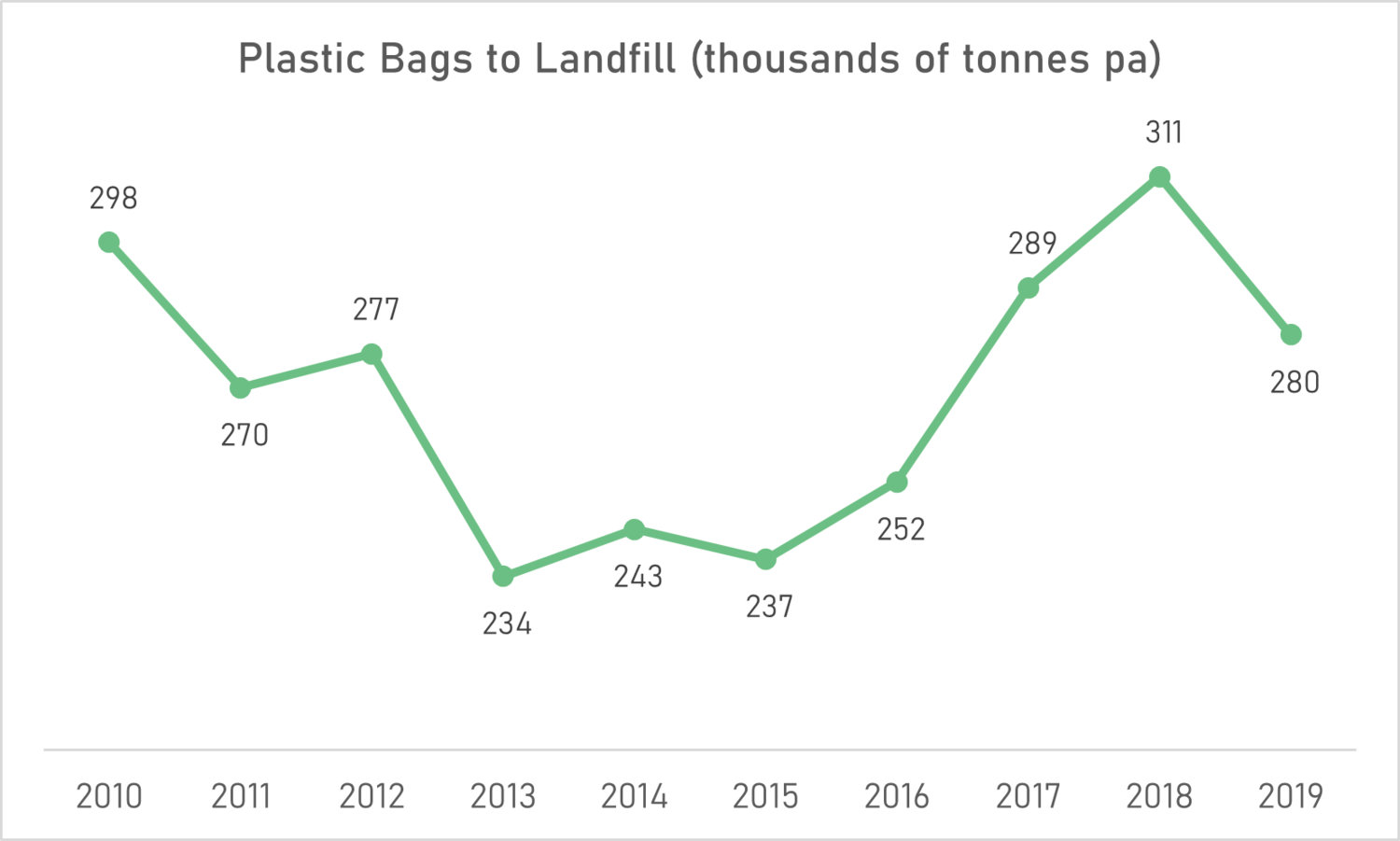

In the 10 years since the introduction of the plastic bag PRS, the amount going to landfill has decreased from 298,000 tonnes per year to 280,000 tonnes in 2019. However, while there was initial success, the amount has steadily crept upwards since 2013.

While the exact model for plastic bags differs from the new plastic bottle scheme, its historical performance provides a clear indication of the government’s ability to adapt and improve on environmental measures. The initial success would suggest that the levy worked in discouraging use of plastic bags, but the levy amount has remained unchanged at HK$0.50. It seems that the public has since accepted the fee and the government has not responded to drive further reductions.

2. No Targets

It’s quite shocking that there are ZERO targets in the proposal: neither in terms of recovery rate nor timeline. Lack of transparency around the current state of recycling in Hong Kong has already eroded public trust. Without targets, there are no means to measure the success of the scheme or how to drive its evolution going forward (an issue we have seen already with the plastic bag policy). It also means there are no incentives for the stakeholders to invest in improving the system.

3. A Tiny Financial Incentive

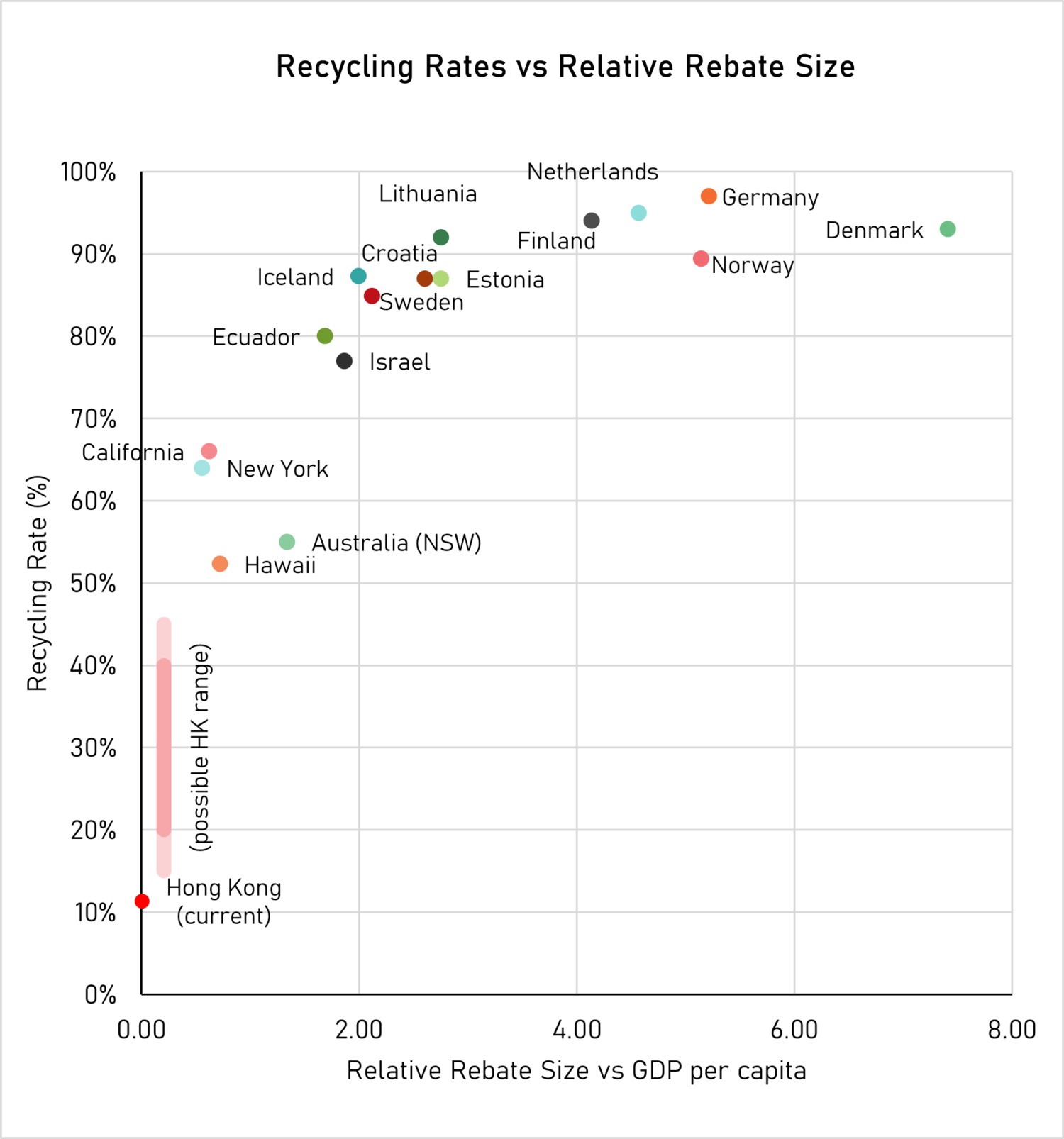

Compared to similar schemes internationally, Hong Kong’s proposed rebate of HK$0.10 (US$0.01) per container is the lowest. In terms of rebate value, the second smallest is Ecuador, who’s deposit value of US$0.02 is nearly double Hong Kong’s.

This tiny incentive is compounded by Hong Kong’s high GDP per capita of US$62,496. Relative to GDP per capita, Hong Kong’s rebate is 2.7x lower than the next smallest (New York) and versus Ecuador, is 8x lower with Ecuador’s GDP per capita just US$11,879.

Upon introduction in 2011, Ecuador’s PET bottle recycling increased from 30% to 80% in just 1 year.

All the evidence from other countries points to a strong correlation between recycling rates and financial incentive size, especially relative to the population’s prosperity.

4. An Inconvenient Recovery Network

A 2019 Deloitte report notes that a major contributor to success is a convenient return network. While Hong Kong’s current proposal will place many return points inside supermarkets, which provide good geographical coverage, most beverage containers are consumed on-the-go – between homes, offices and places of leisure via public transport. Would a consumer make a detour specifically to return a bottle for 10 cents? It would therefore seem sensible to prioritise coverage in those on-the-go areas over supermarkets. Furthermore, these more public spaces would allow Hong Kong’s informal waste collectors, such as the cardboard grannies, to work freely without entering and exiting stores where they may not be welcome.

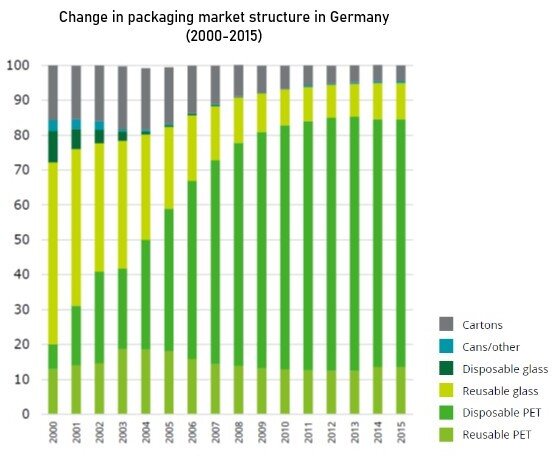

How quickly convenience affects consumer behaviour cannot be underestimated. In Germany, the disposable bottles return network was more readily available as it was compulsory for shops to have them. Reusable return points were only voluntary and thus, more difficult to return. Within just 3 years, disposable plastic bottles gained a dominant market share, rising from c.23% to over 50%.

5. Exclusions On Other Beverage Packaging

A repeated criticism of the proposed rebate scheme is that it does not cover other types of beverage packaging such as cartons, pouches or cans. There is a risk that beverage suppliers may choose to switch their packaging materials to ones not covered under the scheme, undermining the schemes aims.

There will be similar pressure from the consumer’s side. If the value of the rebate for different packaging varies, it can begin to skew customer behaviour in unintended ways such as potentially purchasing more plastic bottles (viewing the rebate as a potential additional income stream).

Packaging changes are particularly relevant in Hong Kong as ready-to-drink teas are the second most popular beverage segment and can be easily switched to carton packaging.

6. Hidden Costs

There are 3 major cost areas not currently accounted for in the proposal: network infrastructure, communication campaign and compliance costs.

To establish the scheme, there will need to be significant investment and while local recycling infrastructure has been given a boost through the government’s ‘PARK’ developments, the return network is in its infancy. Reliance on reverse-vending machines (RVMs) could prove an expensive mistake due to their high initial cost, relatively slow processing time (approximately 10 bottles per minute) and capacity. Deloitte reported that even with an RVM in every convenience store, each machine would need to be emptied 11 times a day to deal with every bottle bought.

Changing current consumer behaviours is also a key factor and there is no clear plan for how the public will be educated on the PPRS. The government has already come under criticism for low public awareness of the free disposal service for waste electrical equipment. A wide-reaching campaign will be needed to educate the public on what they need to do to make the PPRS work – namely selectively sort and clean their trash.

Hosting the critical return points will not be cost-free to retailers either. Ongoing administrative and compliance costs incurred through preparing the returned bottles for collection, additional hygiene measures and space required will all have to be paid for.

7. Limiting Return Network Operator Efficiency and Investment

The Return Network Operators’ (RNOs) must be able to profitably collect the waste bottles for the scheme to succeed. And although the government aims to encourage local SMEs by limiting the network size of any single RNO, it also prevents them achieving economies of scale. RNOs are, ultimately, logistics companies which means scale matters.

The government will also be under constant pressure to manage down costs, most notably by lowering contract values to RNOs. Operators are not incentivised to invest in improving operations if they cannot capture the increased profits. This will lead to chronic under-investment by the operators, limiting the total effectiveness of the PPRS.

8. No Fee Modulation

The proposal would charge a flat fee for all plastic bottles.

Fee modulation is making small adjustments in the levy charged to suppliers to incentivise environmentally friendly packaging innovation. It is a key recommendation from organisations such as the OECD, IEEP and WWF. Initiatives such as light-weighting or increased recycled content are examples of more sustainably packaging and should be recognised and rewarded.

Final comments

The PPRS has come under heavy criticism from many environmental groups stating that the proposal is not even fit for purpose, let alone ambitious. Looking at the details, it certainly seems so. The main reasons it looks set for failure are:

- There are no targets. Difficult to comprehend that no targets have been set but without a goal, there will be no indication whether the scheme is making an appreciable difference.

- The rebate size is simply not high enough. Hong Kong is a highly developed, wealthy territory. As such, it is difficult to imagine that any meaningful success will be achieved when offering the lowest rebate in the world both in absolute terms and relative to income levels.

- The organisational structure does not correctly incentivise all parties to pull in the same direction. Without targets, incentives and penalties, it is far too easy for stakeholders to point fingers at each other. With a set target, and responsibility for meeting those targets placed firmly with the producers, there are greater incentives for an effective, cost efficient operation to be created.

The scheme will also likely impact the cost to consumers. The guidance is that suppliers will need to be charged a total levy of 50 – 65 cents per bottle to cover the costs, so consumers could expect to see price rises in this range and likely more once the aforementioned hidden costs are passed on. It should also be considered that the majority of beverages in convenience stores are priced in 1 dollar increments so consumers may well see prices rise by double the cost of the scheme to the suppliers.

It is difficult to come to this conclusion, particularly as the government is clearly trying to take positive action. We must recognise and support the intent, while also holding the proposal to account. In many ways, it is better that something is passed than nothing at all. It just tends to be better to start right rather than do it over.

This post originally appeared on Please Drink Sustainably and has been republished with the author’s permission. Read the original post here.

Lead image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.