Circular Food Systems Are The Answer: Findings From The First Major Study On Their Potential

6 Mins Read

A new study suggests that we don’t need to wait for techno-based solutions to make our food systems more sustainable.

If there is a way to make our food systems more sustainable without having to wait for a technological miracle, whether it’s for cultivated meat to hit the supermarket shelves or carbon capture and storage to reach the scale we need, will we do it?

This is not a hypothetical question because such a possibility already exists, according to the lead author of the first major study on the potential of circular food systems in Europe.

The paper, published in Nature Food last week (Apr 17), showed that adopting a circular model could have a significant impact on the amount of land we are using to grow food, feed, and fuel, as well as on agriculture’s contribution to emissions, two key elements that make our current food systems unsustainable.

The researchers, mostly from the Netherlands’ Wageningen University, compared four scenarios – the current system, one where the focus is on maintaining our current food supply without imports (CirAgri), one where a redesigned system produces enough healthy food for everyone in the European Union plus Britain (CirHealth), and one where the redesigned system can produce healthy food for hundreds of millions of additional people (CirPop+).

“We calculate a potential reduction of 71% in agricultural land use and 29% per capita in agricultural greenhouse gas emissions while producing enough healthy food within a self-sufficient European food system,” they said.

These savings will become really handy in case of a global food shortage, they added, because the land that is freed up could be used to feed an additional 767 million people outside the EU, nearly 150% of the bloc’s current population.

“Our study so far builds on today’s production systems, meaning that yields are today’s yields under today’s practices. In other words, the redesign we propose are all things we can do today,” lead author Hannah van Zanten told me via e-mail.

“It doesn’t require new fancy technologies. It does, however, require from us a change in mindset. We need to value what we have in a different way,” she said.

“I understand this is difficult and it might be easier to let technology solve our issues instead of changing our behaviour but we should not forget that we can do it,” added Hannah, associate professor of circular food systems at Wageningen and a visiting professor in the Department of Global Development at Cornell.

The Premise and The Promise

I’ve written before about circular food systems and Hannah’s work a few times, most recently about 10 months ago after moderating a panel discussion on these issues.

In case you’re a new subscriber, this is how Megan Deeney, a researcher on circular food systems at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, described circularity.

It “promotes reducing, recycling, reusing and repurposing food system resources so that we really ease the burden on raw materials and natural resources and maintain the value of those resources for as long as possible whilst reducing or potentially even eliminating waste.”

Hannah and her team’s vision of a circular food model is based on four key principles – the system must be within planetary boundaries, the food produced must be nutritious, waste must be avoided as much as possible and unavoidable waste should be recycled.

This means residues and byproducts from crops and processing, as well as waste from animals and humans, become organic fertilisers or feed. Hannah also sees overconsumption, which afflicts wealthy countries, as a kind of waste, because it causes the unnecessary production of food.

There are “a million potential scenarios” we can consider but the researchers decided on four for this study because as the first major research paper on this issue, they wanted to find out what would be possible.

They also focused on different types of circularity. For example, the CirAgri scenario applies circularity principles to the production side. The CirHealth and CirPop+ scenarios apply them to both production and consumption.

Currently, agricultural land in the EU amounts to 172 million hectares (Mha), of which 105 Mha are croplands and the other 67 Mha are grasslands. Croplands are dominated by cereals and oil crops, grown to feed both humans and animals.

In general, CirAgri and CirHealth show a trend towards fewer cereals and fewer fodder crops, and more diversity, particularly for CirHealth where relatively more land is used for pulses, sorghum, green and red vegetables, and tropical fruits.

CirHealth and CirPop+ show large reductions in beef cattle, pigs, and broilers. Dairy and fish show relatively small changes in CirHealth while they largely increase in CirPop+.

Hannah said she personally found CirHealth to be the most promising scenario.

“It shows a large reduction in agricultural land use, allowing us to really think how we can use this spare land to enhance biodiversity while still largely reducing GHG emission. Especially if we then also transition toward sustainable energy, this scenario becomes super interesting,” she said.

It does mean a change in the ratio between animal and plant proteins: from 60:40 currently to 37:63 (so almost a reversal). Most animal proteins see a reduction, but red meat and chicken make up the majority.

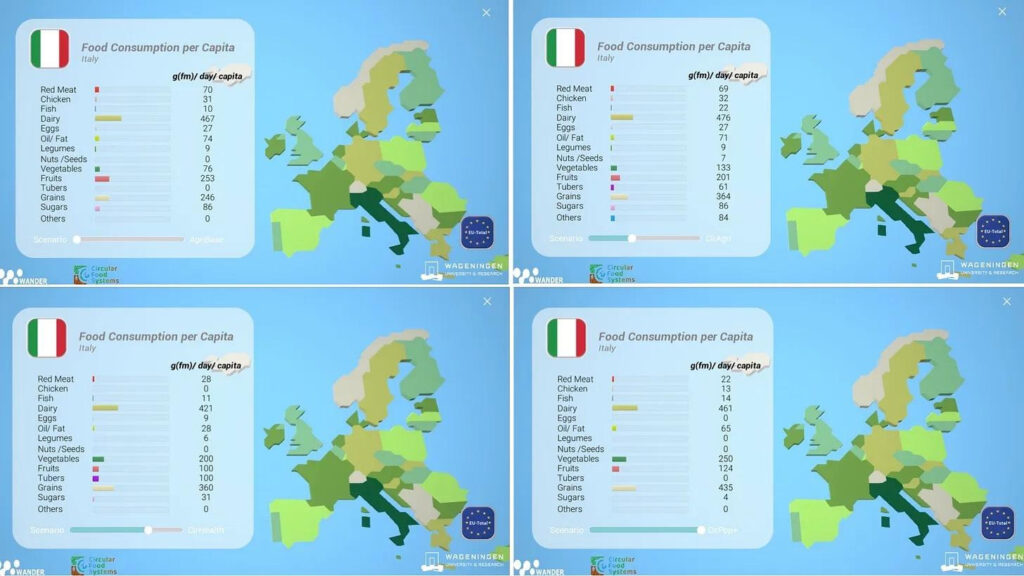

The supplementary data and the Circular Food Systems Dashboard give detailed pictures of the changes, what to produce more and what to grow less, and what is the current state-of-play in EU member countries. The Dashboard can take a while to load so be patient but it’s worth playing around.

BTW: thanks to the institutions behind this research for making all the important information open access! I have said this before and will say it again – it’s a real loss when publicly-funded important research sits behind a paywall and is accessible only to a small subset of readers.

What Do We Value?

Given my background growing up in a poor, food-insecure country like Myanmar and given I’ve spent over a decade reporting on humanitarian crises, I find CirPop+ quite interesting, particularly because of the trade-offs involved. This scenario “makes the EU an exporting country” in case that’s necessary due to food insecurity elsewhere.

In this scenario, the environmental impact of a healthy diet per person goes down but the overall impacts in terms of emission, land use and the use of artificial fertilisers go up.

Of course, such a scenario is bad news for biodiversity in the EU and probably politically impossible to sell to constituents too. But it also makes me wonder – the EU can have the most efficient, net zero, circular food systems, but if the rest of the world continues with business-as-usual, will the overall impact still be a win for the environment?

“We indeed don’t know if (EU having the most sustainable system) will be enough to help respect planetary boundaries. But what’s the alternative? I don’t think we have one. I think we should all take our responsibility. And yes, it might feel a bit depressing if we don’t see others changing with us but someone needs to start and I think we in the EU are in the position to make a start,” said Hannah.

The researchers are very upfront about the limitations of their modelling and the data they use and Hannah said the precise reductions might vary in real life but the overall findings – that investing in circularity will help us to reduce the environmental impact of our food system’ – is still sound.

“We do stress the uncertainties as I believe we don’t do this enough in science. We should be much more transparent about data limitations so hopefully governments and industries pick this up and help us with creating an infrastructure in which data becomes open access and is usable for everyone. This would really help us!”

Next steps? More modeling, but at a global level.

“Circular food system redesigns do not depend on future technologies—they can largely be implemented tomorrow—but they do depend on social acceptance and a radical transformation of the economic sector. To achieve the needed changes, stakeholders need to be aware of the urgency and reach consensus on the direction of redesigns,” the researchers said.

This is an edited and web-adapted version of the 21st April 2023 edition of the Thin Ink newsletter, a weekly publication on food, climate and where they meet by journalist Thin Lei Win – subscribe here.