Uncovering the Ugly Truth Behind India’s Shrimp Farming Industry

11 Mins Read

Food and climate journalist Thin Lei Win speaks to Ian Urbina, executive editor of The Outlaw Ocean Project, about the organisation’s investigation into India’s shrimp farming industry.

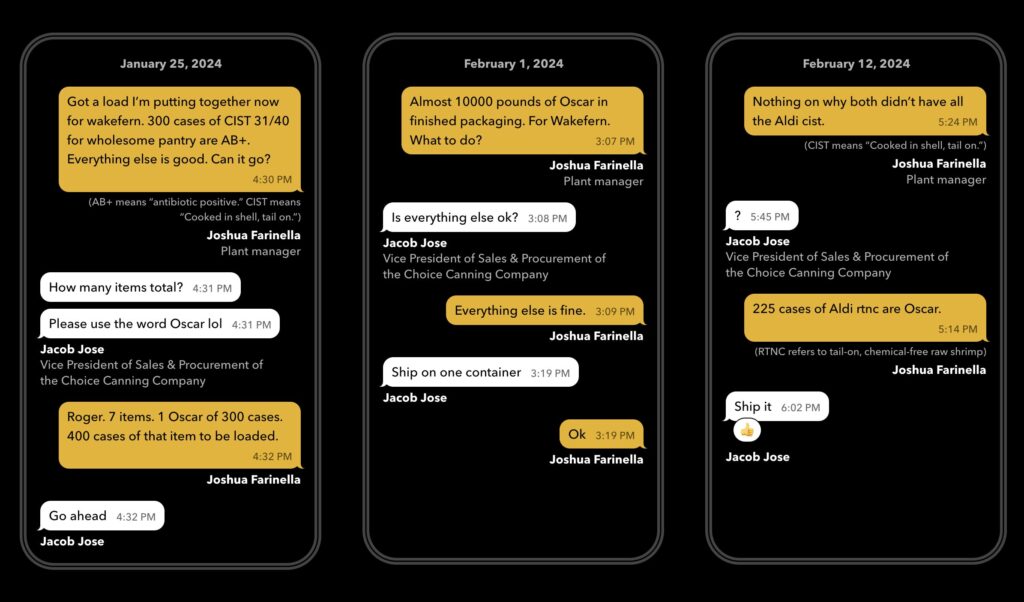

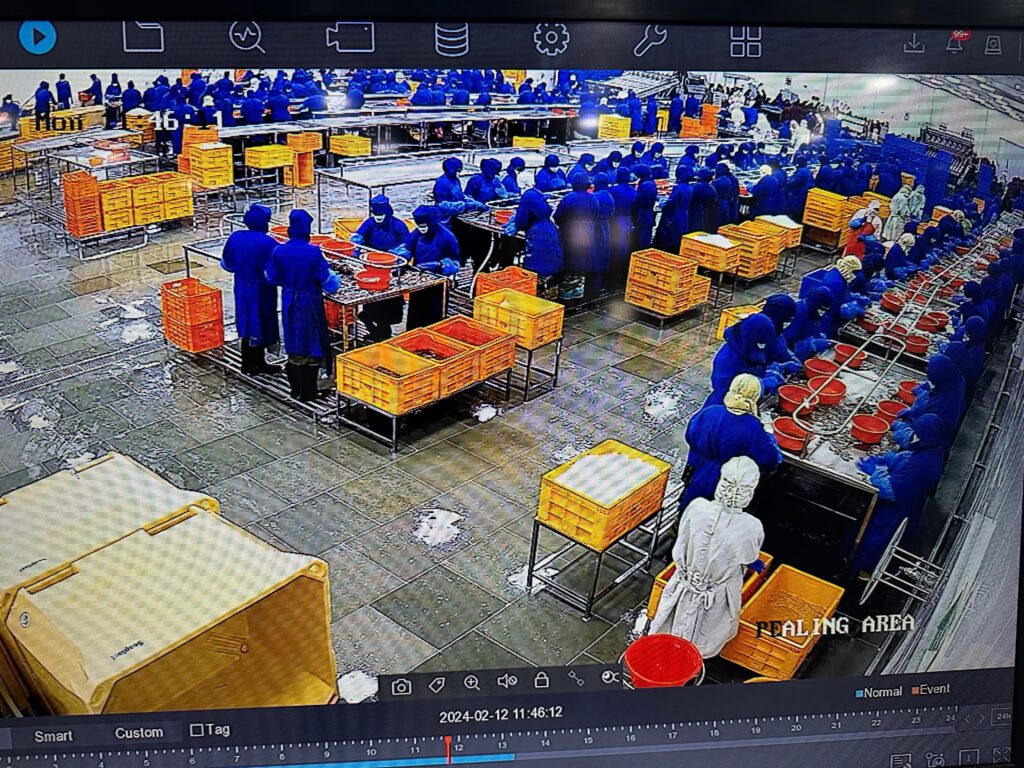

On March 20, The Outlaw Ocean Project, a Washington D.C.-based non-profit investigative outfit that focuses on wrongdoings in the oceans, published a bombshell investigation based on a treasure trove of internal company documents, emails, and WhatsApp messages, as well as footage from security cameras at a shrimp processing plant in India.

The evidence, provided by a courageous whistleblower, showed multiple levels of wrongdoing, from the terrible living and working conditions the workers had to endure to falsifying documents to say they source shrimp for certified farms and knowingly shipping contaminated products.

The plant was leased by Choice Canning, a company whose exports have “filled frozen food sections at stores such as Walmart, Price Chopper, ShopRite and Hannaford with a little over 19 million pounds of packaged shrimp”.

The company’s “Tastee Choice” brand products are sold in commissaries at 29 U.S. Military bases spanning 23 states across the country and Washington, D.C., said the Outlaw Ocean Project, so this isn’t exactly a no-name company.

On the same day, Associated Press published an article and video news story about the gruelling conditions in Indian shrimp industry, confirming the findings of a report – Hidden Harvest – from the Chicago-based Corporate Accountability Lab, a human rights legal group, that came out a day earlier.

I reached out to Ian Urbina, executive editor of The Outlaw Ocean Project, and someone I’d interviewed before on illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing for The Index podcast over a year ago, to find out about this latest investigation, titled, “India Shrimp: A Growing Goliath”.

The conversation below has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

Q: Can we perhaps start from the beginning? How did the story come about and what the findings are, for those who may not have read it?

A: It emerged in a kind of funny way. An individual who was working at a large seafood company was in the room during several fairly tense meetings we had with that company about findings of forced labour in their plants in China. He left that company and took what looked like a dream job for him in India to run a new plant.

Several months into that new job, he sent me a note on LinkedIn and said, “You don’t know me but I know you. I came to really respect the work you guys do. I am at a plant where I’m seeing things that are disturbing and probably illegal and I’m not sure what to do.”

I was on a ship at that time in the Southern Ocean, so I got on the phone and talked with Josh Farinella, the whistleblower and I spent the next week or so vetting him. I really checked him out to make sure he wasn’t fake and was honest, and the more I talked to him by text and by satellite phone from the ship, the more I realised this was an unusually strong whistleblower because he had access to large amounts of very compelling documents. And those documents could make this a stronger revelation.

That’s always the key thing with whistleblowers – how can you corroborate what they’re saying? He also just kind of checked out in the subtle ways in which reporters check on the credibility of sources. His stories didn’t wobble. Details didn’t shift.

We were supposed to be at sea for a month and we cut that short and. My visa to India wasn’t approved but my videographer got his. So we sent him in to go meet the whistleblower at the plant, to film conditions, and to get the documents in person. Meanwhile, we were digitally receiving thousands of pages of emails and recordings and all sorts of evidence.

The outcomes of the investigation is that a plant in India that was operated under a lease by an American company called Choice Canning, which is a large player in the shrimp export arena – over a third of all shrimp in the US is coming from India – had very serious problems with what seemed to be captive labour and also food safety concerns specifically tied to antibiotics in shrimp that seem to have ultimately been shipped to the US and Canada and elsewhere.

Q: There were so many levels of wrongdoing – the forced labour aspect, the hygiene and food safety issues, the antibiotics issues, just to name a few – that it was quite staggering. Is it something that you see quite regularly when it comes to problems with seafood supply chains?

A: You summed it up well. If you imagine it as layers, you’ve got the layers of, generally speaking, the treatment of workers and you’ve got lots of parts in there, their wages, their living conditions, their work hours, their hygienic expectations. Even within wages, you have delay of wages, non-payment of wages, lots of layers in the labour-human rights category. There are captivity concerns – they are not allowed to leave without permission.

Then you have the food concerns – the antibiotics, the unhygienic stuff. Is the stuff clean, does it have things in it that it shouldn’t have?

But then you have the more boring and I think in some ways, more consequential and fundamental problems, which are auditing and tracking. Because there’s an industry that’s supposedly meant to police those other things, right and that whole industry does not work, and often is worse than ineffective. It’s actually complicit in the deception of the consumer and the companies. And that was the case here where there was evidence of wilful deception by the company and the auditing firms.

And that to me is the the deepest layer because it’s one that traverses India, it takes you to China and takes you to other industries, like garment in Bangladesh, and the auditing and check mechanisms that are meant to reassure companies and consumers even when they’re trying to do well, is pretty ineffective and oftentimes, they’re more just trying to do PR. So I think that’s the deepest layer of problem that we unveiled.

Q: What’s the response been so far? Lots of media have picked it up but there’s also been a Senate committee or political players actually trying to find out what happened, right?

A: Yeah, so I put the “what happened next” in three categories.

One is… to be fair and balanced, there’s the Indian pushback. Just to be a good reporter, let’s just deliver what they say, whether we believe it or not. That “This is a liberal Western competitively-motivated campaign to undercut a growing Indian industry, and it’s attempting to tarnish our reputation with false claims because the US shrimp industry, the domestic industry is not competitive, and it’s clawing its way back into the market”.

The liberal cabal card has also been put forward by the company itself and by the industry association and by the government, which is to say, these human rights organisations and these liberal journalists are just out to have a good story and claim terrible things that aren’t there. That’s one form of pushback. It’s completely wrong, but it’s worth giving them their chance.

The second category is a lot of other news outlets picked up the story and ran with it and amplified it. Great.

And then the third is various stakeholders. I would divide them into lawmakers and executive branch folks. The lawmakers… several congressional offices have asked for the documents. Maybe they just were riding the media wave but don’t have any real intention. But they asked me and they asked the whistleblower and his lawyer for all the documents and they’re going through them. Whether that will result in legislation, a hearing, a letter, who knows?

The second category outside the congressional or lawmaker realm is the executive branch. A formal whistleblower complaint was submitted by the lawyer of the whistleblower to multiple agencies, the FDA, Customs and Border, Department of Labour, and Department of State. These whistleblower complaints emphasise different parts. So we’ll see.

But those are the three big impacts. I will point out though, that strategically, the company on the chess board played a very smart move which was probably what they should have done at the outset rather than threatening us and trying to intimidate us with legal letters. They instead, in stage two, went for, “We’re closing this plant, and we’re opening a new one and everything’s going to be great there”. That’s the logical PR move.

(Thin: you can see at least one letter threatening lawsuit here.)

Q: So the company’s move – that they’re shutting this plant down and opening a new one. It feels a little bit like “Whack-a-Mole”. Labour exploitation and problems within the seafood industry is is not new, right? Because it happened in Thailand years ago with the Burmese workers. It moved to India and now it’s shifting from one place in India to another place in India. Is that just the modus operandi?

A: I mean, I think it’s an even bigger story about how foreign capital operates, if you want to go meta. I think foreign capital just moves when things get hot, whether it’s environmental issues or killing people. In the Amazon logging, it’s the same story. Investors move.

But yes, I think the hope here, though, journalistically, is that when you engage in the “Whack-a-Mole” journalism that we’re engaged in, if you can whack big – I don’t know how to keep the metaphor – but if you can do it the right way, you get deep enough that big brands start asking hard questions of those no-name players like the auditing firms.

That you’re doing a follow up story is gold. This is where change happens when folks do stories a month and a half later because you extend its duration the news. And that’s how auditors and big brands started saying, “Hey, we’ve got to fix this for real”. It doesn’t solve it but it could well improve it because they’re more sceptical and asking better questions of their auditors or maybe switching to different kinds of auditors. Whatever.

Q: What about in terms of from consumers, the ordinary people who enjoy having shrimp at a cheap price? Do you think there’s a common misunderstanding around where seafood comes from or is it just easier not to look too closely?

A: Look, I don’t think the story here is different for Nike shoes or iPhones or shrimp. I do think globalised supply chains are all rife with hidden deficiencies, buried costs, environmental degradation, and slavery. Those are efficiencies and they’re in all the products.

I think seafood is distinct though. That’s why I left the Times and doubled down on the ocean space because what’s happening out there is different than a sweatshop in Port-au-Prince or Dhaka or the Amazon.

There are sweatshops on the ships and those supply chains are longer, more tangled, more opaque, and therefore there’s a lot more craziness built into the supply chains and I think on the receiving end, the brands have, for a long time, enjoyed the plausible deniability that allows them to not get a lot of attention because (the oceans are) a hard place to report from.

It’s hard to break these stories, it’s costly, it’s slow, it’s complicated with the trade data, etcetera. So I think all that has added up to seafood being a good decade behind garments or blood diamonds, like the fluency of average consumers who are like, “Before I get that fur or that diamond, I might want to check to make sure it’s not coming from DRC”. Whereas with secret, it’s only starting to occur like, “Oh, wait, did you see that story?”

Q: Yeah, like with the salmon farms. Now, was this a collaboration, meaning did you collaborate with a lot of media outlets to push the story out? Or was it mainly an Outlaw Ocean Project thing?

A: China was much more sprawling and more complicated in the collaboration. This was a bit more like Libya in that a collaboration was we did all the reporting, storytelling, video making, etc. And the collaboration that emerged was in the form of convincing editors to run it and that was not an easy sell because of those threatening letters. We had a lot of folks pull out when they saw the letters.

So the collaboration was in distribution more than in reporting although after we reported, we reached out and said, “This whistleblower did something very brave. He probably tanked this career. He’s a working class guy who doesn’t have a whole lot of options. And we as journalists really need to like rally around him. He’s the real deal. The documents in there. Vet it yourself, but I need other journalists to step up.”

So I tried to put the word out to folks and I said, “I need everyone to interview this guy because we need to flash mob around him.” But yeah, folks stepped up and said, “I get it, we’ll interview him and we’ll like put our own thing out.”

Q: Speaking of which, where is Joshua Farinella now? Is he ok?

A: Yeah, he’s great. It’s good. You never know how that’s gonna play out. He gave up a job and took a new job, for, I think a third of what he was making. He moved his family, his wife, his stepdaughter. He’s employed. He signed his contract the day before the story dropped. His lawyer and I were sweating.

He’s in good shape. He’s happy and very proud of what he did, which is great.

Q: Can anything be done realistically to tackle these issues in a more system systematic way? Or will it always be a reactive thing where we respond to bad behaviour?

A: I will answer this as a journalist to another journalist, two people who view the world through the lens of journalists can change the world kind of thinking. I do believe that.

I think that journalism has a huge role to play here in the sense that if we as a group stay on this and keep pressing the core issues of unannounced spot checks versus announced spot checks, big difference. Audits in this form by these kinds of firms that are paid by the very people they’re policing, that’s a worrisome thing, etc, etc.

If we keep pushing that type of story in this industry or others, I’m pretty sure… and we are smarter than historically journalists have been about working with NGOs who can push other levers.

It doesn’t mean we crossed that advocacy line, but it does mean we say, “You guys should sue. You guys should do as a shareholder resolution. You guys should run follow up coverage. You guys should write consumer letters. You Mr. Lawmaker should have a hearing.”

If everyone does those things, trust me, this won’t happen.

This is an edited and web-adapted version of the May 10, 2023 edition of the Thin Ink newsletter, a weekly publication on food, climate, and where they meet by journalist Thin Lei Win – subscribe here.