With Investigations and Regulations Against the Market, Are Carbon Offsets in Trouble?

10 Mins Read

From one greenwashing scandal to the next, carbon offsets have developed a notorious reputation over the last few years. As more investigations call out their inflated claims and regulations clamp down on the sector, could the voluntary carbon market be suffering from a loss of faith?

Whether it’s soil, cookstoves, water bottles, or Taylor Swift, carbon offset credits have been the hotrod of climate discourse in the media (and governments). Touted as a way to feel better about your emissions and footprint – whether as an individual or a company – the sector has encountered heavy criticism over the years for its unsubstantiated, overstated and/or misleading claims.

In principle, carbon offsetting involves “cancelling out” emissions by investing in projects that promise to cut carbon elsewhere – think reforestation initiatives, clean energy production, or carbon capture projects. The idea is, by buying these ‘carbon credits’, you can ‘balance out’ the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

But multiple studies and investigations have revealed that a lot of these crediting schemes are engaging in greenwashing, making promises they can’t fulfil and giving high-emitting corporations an easy way out. The $2B voluntary carbon market has also been dented by legislation like the EU’s upcoming greenwashing ban.

Even in the last month or so, there have been a host of stories uncovering how the capabilities of carbon offsets have been overstated, which begs the question: are we finally losing faith in the practice?

Clean cookstoves aren’t really clean

Last week, a study revealed that clean cookstove projects – a class of carbon credits that trade smoky fuels for alternatives like electric cookers – have been overstating their climate impact by around 1,000%. These schemes are presented as “nature-based solutions” that can bring health, social and environmental benefits to people in the developing world by enhancing air quality, reducing the time people spend collecting wood, and slowing forest loss.

Clean cookstove initiatives sell greenhouse gas reductions as carbon credits, allowing many buyers to label their products or services as carbon neutral. With 3.2 million premature deaths happening manually due to household smoke caused by cooking fuels, which cause 2% of global emissions, these are wildly popular too: between May and November last year, 15% of all carbon credits were issued by these cookstove schemes, which also registered the highest number of projects in this period.

But the study, published in the Nature Sustainability journal, revealed that nine in 10 of the 96 million certified cookstove credits don’t avoid the emissions they claim. The project’s sample, which covered 40% of these credits, found that cookstoves were over-credited 9.2 times. Extrapolating to the entire market, this rises to 10.6 times. Such overcrediting comes mostly from exaggerated estimates of stove adoption and use, underestimates of the continued use of the original stove, and high estimates of the impact of fuel collection on forest biomass.

The findings have been disputed by leading carbon certifiers Verra and Gold Standard. The latter, whose credits were found to be the highest-quality ones (over-crediting just 1.5 times), said it had interacted with the authors and taken suggestions. But Verra expressed disappointment over continued attention on the study, saying the findings were “at odds with the wider academic literature and expert view on this subject”.

Carbon angle on regenerative agriculture ‘oversold’

This is just one of a number of different developments hindering the voluntary carbon market. For instance, there has been a spotlight on regenerative agriculture and soil carbon sequestration. The agrifood system already accounts for a third of all global emissions, leading food companies to look for ways to cut their climate footprints: one way of doing so is by adopting regenerative farming practices.

But some say this will not solve the industry’s emissions problems, with questions raised over how much (and for how long) carbon can actually be stored in soils. As the Financial Times reports, scientists warn that “if sequestration seems too good to be true, it probably is”. Only a handful of agrifood companies disclose how much their net-zero goals depend on using land as carbon sinks, but Pete Smith, professor of soils and global change at the University of Aberdeen, told the publication that the numbers “simply won’t stack up” because soil can’t perpetually soak up carbon.

Climate experts have likened this idea of carbon storage in soil for offsetting emissions to the wider carbon offset market, which – as mentioned above – has been “derided by some campaigners as a vehicle for corporate greenwashing”. That still hasn’t stopped startups from selling soil-based carbon credits on the voluntary market. While regenerative agriculture “makes a lot of sense”, Smith feels “the carbon angle has been oversold”.

Danone’s water bottle battle

In the US, Danone is facing a class-action lawsuit for allegedly misleading consumers with a ‘carbon neutral’ claim on the packaging of its Evian bottled water. The plaintiffs argue that people “would understand and believe that the term ‘carbon neutral’ means the manufacturing of the product, from materials used, to production, to transportation, is sustainable and does not leave a carbon footprint.”

In response, Danone stressed that “no reasonable consumer would interpret carbon neutral to mean that the product does not emit any carbon dioxide whatsoever during its entire life cycle”. It added: “One wonders how the plaintiffs think the product magically arrived from the French Alps to their homes without the emission of even a molecule of carbon dioxide.”

It’s a classic greenwashing lawsuit, but illustrates the problems posed by a lack of legal definitions for terms like ‘carbon neutral’. The WWF explained this in a public comment. “Failing to address these misleading claims allows both of the following hypothetical companies to claim carbon neutrality,” it wrote. “Company A: Reduces 99% of scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Buys carbon credits in a volume equal to the remaining 1% of emissions. Company B: Reduces 0% of scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Buys carbon credits in a volume equal to their total emissions.”

Is Taylor Swift burning red?

Carbon offsets aren’t safe from discourse even around the world’s biggest pop star, Taylor Swift. The 34-year-old has been in the news for her private jet emissions since 2022, when she was named the biggest celebrity polluter of the year. But the conversation was amplified recently when a now-defunct Instagram page called Taylor Swift’s Jets tracked her journeys on private jets and calculated her emissions to be 138 tons in just three months.

This equates to the annual emissions of 28 gas-powered cars or 16 homes, but Swift made further headlines after her representative pointed out that before the start of her record-breaking Eras Tour in March 2023, she “purchased more than double the carbon credits needed to offset all tour travel”.

But it’s unclear where the Anti-Hero singer bought these offsets from, and highlights the problem of misconceptions around carbon offsets on a global level. It will be interesting to see if Swift’s carbon credits would be subject to California’s new anti-greenwashing law. “If Swift or her companies have publicly claimed that the tour was carbon neutral or that it produced less climate impact than its actual emissions because of offset credit use, then arguably they have made a claim that is covered under AB 1305,” carbon market expert Danny Cullenward told the New Republic.

Lawmakers clamp down on carbon offsets

On to the regulations, then. Just like Swift’s carbon emissions may be affected by legislation, cases like Danone’s lawsuit would also become much less ambiguous with proper rules and definitions. This is what California has done with AB 1305, which mandates carbon offset sellers to disclose specific information about accountability measures if projects aren’t completed or don’t meet the target objectives.

Plus, businesses who buy these offsets and make claims like ‘net-zero’, ‘carbon-neutral’, etc. are required to be transparent about the accuracy of these claims, their progress, and whether they’re verified by an independent third party. Speaking of which, the bill includes third-party verification of all of the company’s GHG emissions, identification of its science-based targets for emissions cuts, and disclosure of the methodology used for the same.

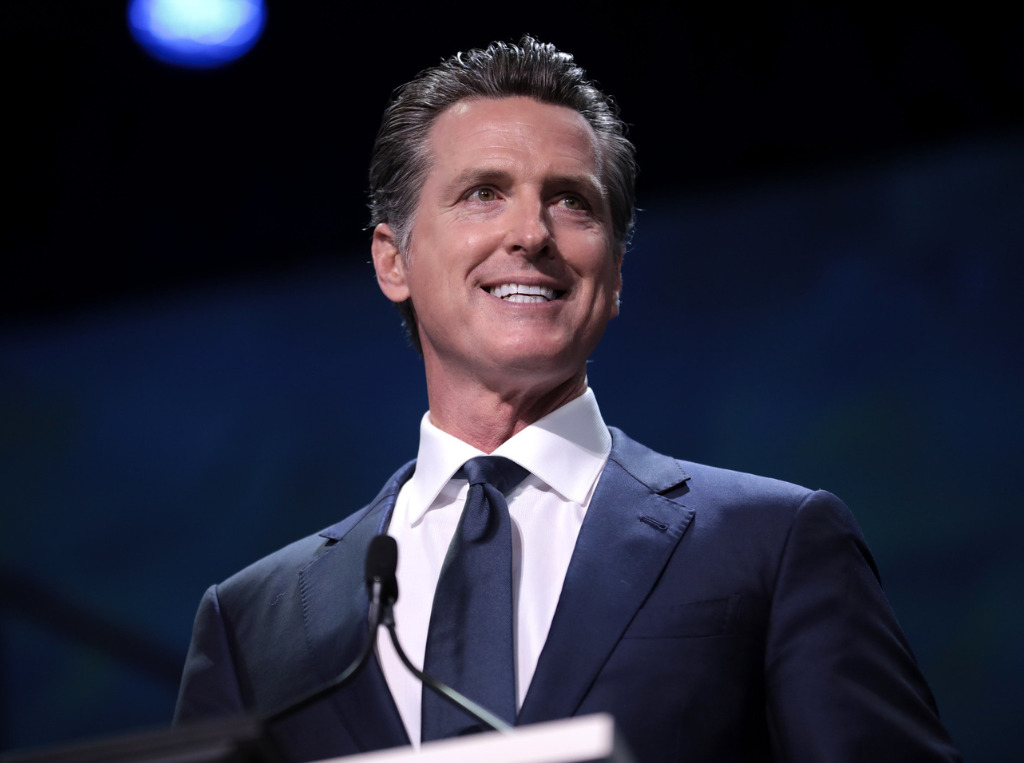

Passed by governor Gavin Newsom, the aim is to introduce transparency and combat greenwashing, holding businesses accountable for claims they make about their climate impacts. Those found violating the law could be penalised $2,500 for each day that information about carbon offsets is unavailable or inaccurate on their website. This is capped at $500,000, which could potentially be recovered in civil actions.

Across the Atlantic, the EU has passed its own anti-greenwashing law, which will come into effect in 2026. It means companies can’t use terms like ‘carbon neutral’, ‘eco-friendly’ or ‘green’ without providing substantial “proof of recognised excellent environmental performance”. This will heavily impact the voluntary carbon market, as businesses buying these offsets won’t be able to make such claims.

“We are clearing the chaos of environmental claims, which will now have to be substantiated, and claims based on emissions offsetting will be banned,” said Biljana Borzan, a Croatian EU lawmaker.

For instance, airlines allowing travellers to pay a small fee to offset their flying emissions will no longer be allowed to make carbon/climate-neutral claims. “There is no such thing as ‘carbon-neutral’ or ‘CO2-neutral’ cheese, plastic bottles, flights or bank accounts,” said Ursula Pachl, deputy director of consumer advocacy group BEUC. “Carbon-neutral claims are greenwashing, plain and simple. It’s a smoke screen giving the impression companies are taking serious action on their climate impact.”

Gilles Dufrasne, global policy lead at Carbon Market Watch, added: “The EU is sending a powerful signal to the voluntary carbon market: the era of offsetting is over, and carbon credits can’t make up for buyers’ pollution.”

Voluntary carbon’s troubles – or are they?

Such legislation puts into doubt the credibility of carbon offsetting, and it’s crucial. The sector is set to be valued anywhere between $10B and $40B by 2040, but there aren’t enough trees to capture a sufficient amount of carbon to make up for our emissions, especially since it can take about 20 years for tree saplings to become viable for carbon offsetting.

According to one investigation, 85% of offsetting projects commissioned by the EU have failed to reduce emissions, and only 2% of the covered projects and 7% of potential ones would have a high likelihood of reducing emissions. Another outlined how 90% of rainforest offset credits issued by Verra – which is the world’s largest offset provider – are “worthless”. The company claimed to have cut 90.9 million tonnes of carbon emissions, but only delivered 5.5 million tonnes of reductions.

Verra has additionally been accused of highly inflating its projects’ climate impacts, with some projects unsuitable for businesses to use for carbon offsetting as they aren’t equal to fossil fuel emissions. Another investigation revealed that 28 of its 32 projects analysed were essentially “junk”. In fact, 39 of the top 50 carbon offsetting projects (78%) were classed as junk or worthless due to failures undermining the promised cuts, while eight others (16%) looked problematic and were classified as ‘potentially’ junk.

And in November last year, a report suggested that Verra manages 41 plastic collection and recycling projects across 15 countries, but while 11 of its projects have been registered and three approved to issue credits, only one is actually doing so. And a fifth of its schemes are ending plastic to cement kilns for incineration, a charge levied on plastic credit marketplace PCX too. Only 14% of its plastic offsetting credits are generated from recycling, with the rest coming from incineration in cement kills.

All this has left consumers – and, you’d think, companies – disillusioned. But the carbon offset market is set to thrive this year, with only a 3% drop in demand from 2022-23. A bilateral deal between Switzerland and Thailand could open up a new branch of the global market, while some governments in Africa are taxing offsetting revenues to redirect them back into the communities where projects are located. Oil companies like Shell are doubling down – despite indicating a move away from the market: it bought 16 million tonnes of credits last year (twice more than the next on the list), just as the market opened up to a growing number of first-time purchasers.

Serafino Capoferri, analyst at financial firm Macquarie, told Semafor that the “fear of reputational damage may keep some buyers away, and a dip in prices also cut into the supply of new credits last year”, but barring any major scandals, “the carbon market has contracted as much as it is likely to”.

The key lies here: can carbon offsetting avoid any more scandals?