Could This New 3D-Printed Chip Help Us Quit Animal Testing For Good?

4 Mins Read

2023 could prove to be a landmark year for the fight against animal testing, having started on the back of a legislative win and ending with a technological breakthrough, where 3D printing could eliminate the need to trial new drugs and medicines on animals before being approved for human use.

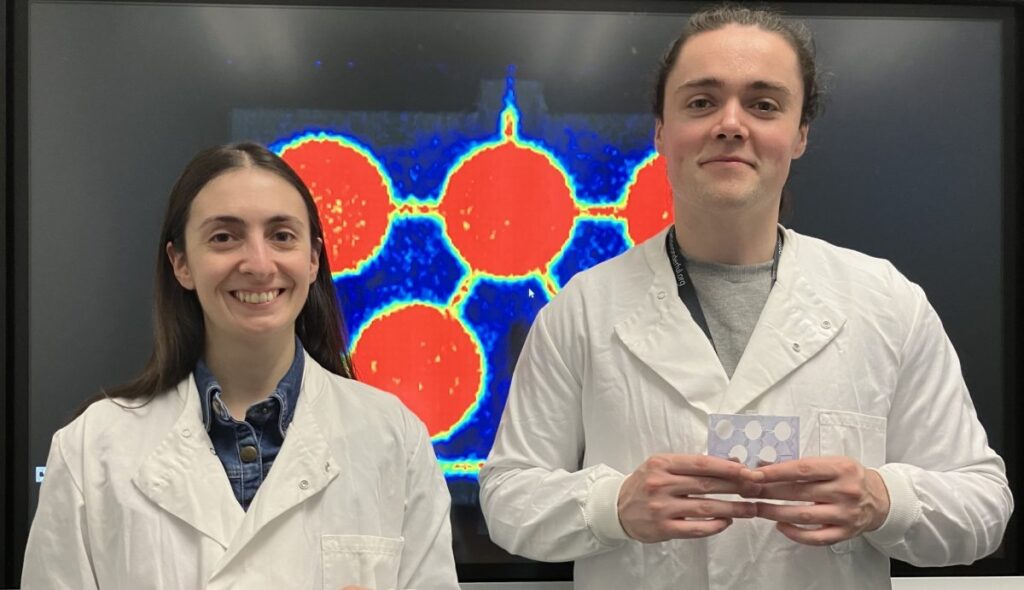

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh have developed a groundbreaking 3D-printed chip that could end the need for live animal testing, as well as speed up patient access to new medicines.

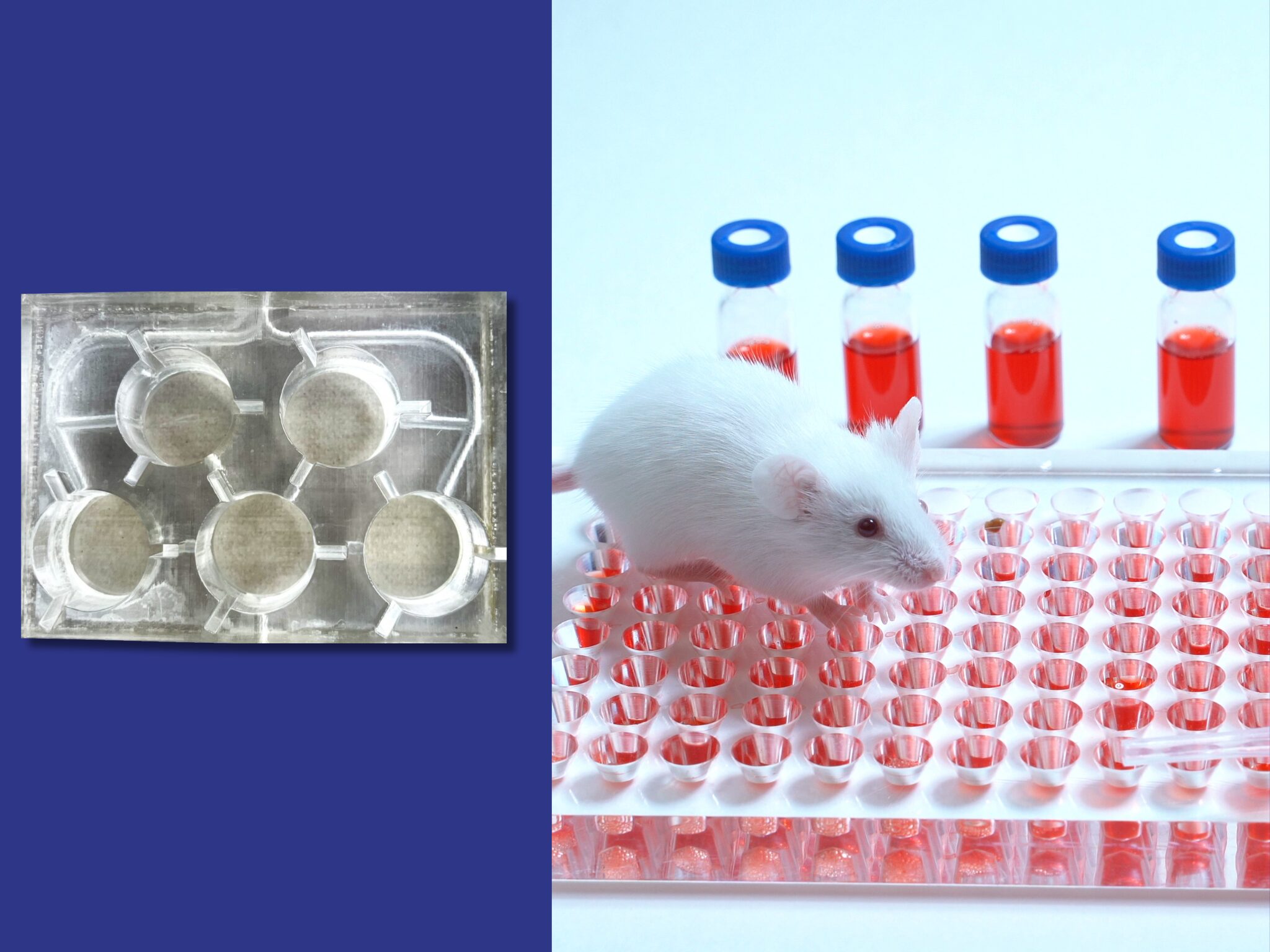

Described as a first-of-its-kind device, the 3D-printed “body-on-chip” identically replicates how a drug would flow through a person’s body, allowing scientists to test them on the human heart, lungs, kidney, liver and brain. These organs are connected with the chip’s compartment via channels that mimic the circulatory system, through which new drugs can enter.

Sidestepping animal testing in drug development

The plastic device uses positron emission tomography (PET) scanning to generate detailed 3D images displaying the reactions inside tiny organs. “The PET imagery is what allows us to ensure the flow [of new drugs being tested] is even,” Liam Carr, the inventor of the device, told the Guardian.

Through this process, tiny amounts of radioactive compounds can be injected into the chip to transmit signals to a sensitive camera, enabling improved analysis of the effect of new drugs.

“This device is the first to be designed specifically for measuring drug distribution, with an even flow paired with organ compartments that are large enough to sample drug uptake for mathematical modelling,” added Carr. “Essentially, allowing us to see where a new drug goes in the body and how long it stays there, without having to use a human or animal to test it.”

While it’s notoriously hard to find official figures around animal testing due to a lack of transparency, one estimate from 2015 revealed that 192 million animals were used in lab experiments that year. One body that is somewhat open here is the EU, which reported that over 8.6 million animals were used for scientific, medical and vet research in the bloc in 2020. But despite these numbers, many drugs tested on animals don’t show any clinical benefit.

“This device shows really strong potential to reduce the large number of animals that are used worldwide for testing drugs and other compounds, particularly in the early stages, where only 2% of compounds progress through the discovery pipeline,” explained Carr’s supervisor, Dr Adriana Tavares from Edinburgh’s Centre for Cardiovascular Science (CVS).

“This is a really important area of medical research, as we continuously learn about how diseases traditionally perceived to be restricted to an organ or system can have diverse effects across other distant organs or different interconnected systems,” she added, noting how connecting these five organs together on one device would could show how a new drug would affect the whole body.

“Devices such as the body-on-chip platform are essential to unravel the mechanisms underlying systemic effects of local diseases as well as investigate off-target effects of drugs, which might be therapeutically useful or detrimental.”

More benefits than just avoiding animal testing

“We’re delighted to be supporting Liam and the CVS team in the development of this ‘body-on-chip’, and we look forward to seeing the impact this novel device has on the testing and progression of new compounds and drugs in the future,” said Dr Susan Bodie from Edinburgh Innovations, the university’s commercialisation unit.

“The platform is completely flexible and can be a valuable tool to investigate various human diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and immune diseases,” added Carrr. “Because of this flexibility, the uses are bound only by the availability of these cell models, and the scientific questions we can think of.

“For example, we could have a fatty liver disease model in the device and use this to see how having a diseased liver affects other organs such as the heart, brain, kidneys, etc, and could even combine multiple diseased cell models to see how diseases can interfere with each other.”

Echoing this sentiment, Tavares outlined how there were more benefits of the 3D-printed chip than just removing the need for animals in early drug development: “This non-animal approach could significantly reduce [the] cost of drug discovery, accelerate [the] translation of drugs into the clinic, and improve our understanding of systemic effects of human diseases, by using models that are more representative to human biology than animal models.”

Developed through the National Centre for Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs) and a PhD grant co-funded by Unilever, the “body-on-chip” could be a revolutionary tool in the fight against animal testing, which began the year on the back of a policy breakthrough, as awareness of the cruelty involved in these lab experiments continued to grow.

While animal testing is required by law during early-stage drug development around the world, in late December 2022, the Biden administration in the US announced that it’s no longer a requirement for new medicines to be tested on animals to receive FDA approval, marking a shift away from an 84-year-old drug safety regulation. And earlier this year, the EU also accelerated its efforts towards an animal-free regulatory system under chemicals legislation, which included human and veterinary medicines.

Another animal testing alternative project is being undertaken at the Institute of Bioengineering of Catalonia. The EU-funded initiative, called BRIGHTER, is using light-based 3D bioprinting tech to engineer tissues by patterning 3D cell cultures, which could potentially be used to produce organs in labs too.

Over to 2024, and the wait for these policies and technologies to come to fruition.