‘Crossing the Divide’: The Four Worldviews for the Future of Agriculture, and How to Combine Them

7 Mins Read

With agriculture’s impact on the climate becoming clearer than ever, there are distinct views on how best to tackle the problem and enable a healthy, affordable and sustainable food system. A new report looks at the most ideal approach.

With agrifood systems accounting for a third of all global emissions and awareness about climate change finally becoming starker by the day to more and more people, there is radical disagreement on the best way to fight the crisis. For example, food security stems from local production for some, while for others, it means raising demands to meet a Western-style diet.

The result of these contrasting opinions is stasis, according to a new report by British think tank Green Alliance. Titled Crossing the Divide, the report argues that policymakers are confused over the best course of action for agriculture, and end up doing little to nothing about it for that reason.

So how can we harmoniously agree to disagree and fix our food system? Green Alliance identified four competing worldviews, and how they can work together to create viable solutions.

The four differing worldviews for the future of agrifood

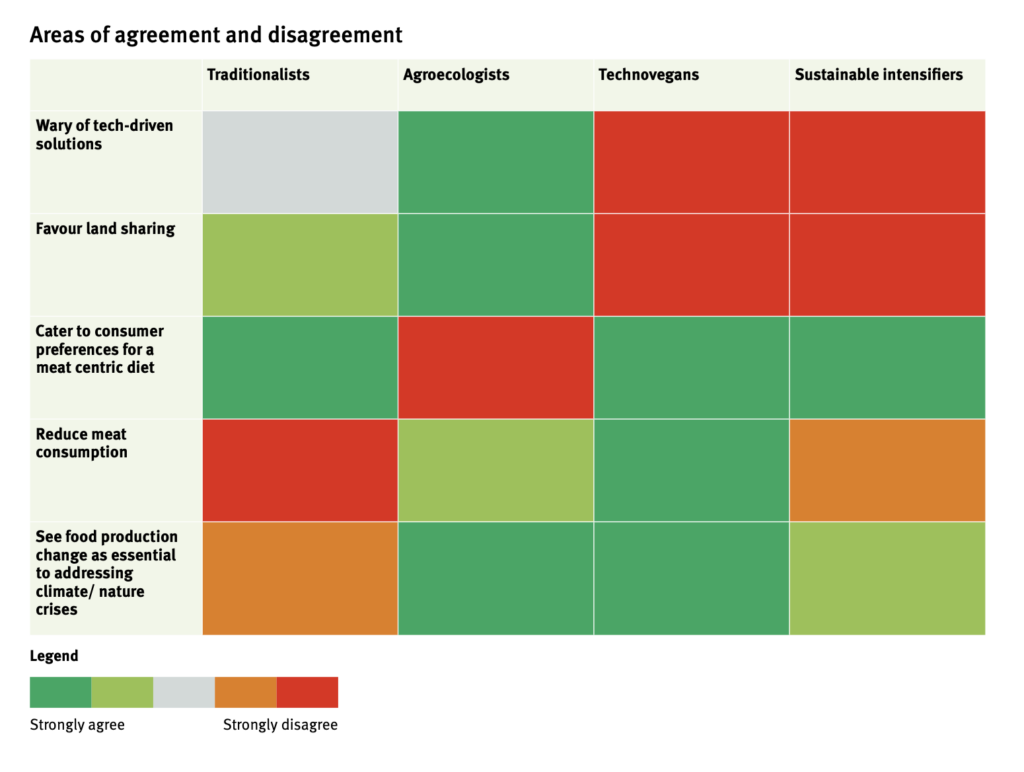

The first worldview – and the most dominant in Europe – belongs to Traditionalists, who are resistant to fast-paced and large-scale changes. For them, farmers need to be valued as food producers and guardians of the countryside and traditions. They take a pragmatic, conservative approach to farm technologies and practices, and don’t see climate change as a specifically big issue for agriculture.

Traditionalists are largely opposed to meat and dairy reduction, arguing that they are nutritionally important and downplaying their climate impact by focusing on the role of ruminants in soil carbon sequestration. This group also believes in free trade for exports, as well as restrictions on imports to protect local systems. But the report outlines their approach – which regards changes to the food system as attacks on farmers – as defensive and resistant to shifts needed to address climate change.

The proponents of the next worldview are Agroecologists, who believe a complete restructuring of the food system is key to shifting power from big businesses to family farmers more in touch with nature. They promote food sovereignty, social justice, and low-intensity, chemical-free farming, alongside localised food systems and ‘slow food’ culture.

For Agroecologists, land sharing is the best way of preserving nature. Since agroecological systems have a lower yield, this group agrees that a significant reduction in meat consumption is needed to live off land without chemicals, and proposes a whole-food plant-based approach that uses meat as flavour instead of a centrepiece. They’re also capitalism-sceptic and reject free trade in favour of local food production, and are thus suspicious of Big Food and Big Agriculture – though their worldview is more comprehensive and demanding than the rest.

Then there are the Technovegans, who see food tech as central to tackling climate change by displacing meat and dairy with alternative proteins and eliminating food production from land and ecosystems. They favour high-tech, capital-intensive solutions, are strong opponents of land sparing, and are at ease with today’s trade and economic systems.

Technovegans don’t believe eating habits will significantly change, so find alternatives to meat, dairy and eggs as the only way to change diets and land use at the pace and scale necessary. This is a more scientific outlook seeing ‘natural’ food as marketing hype, but the idea of plant-based meats being ultra-processed food means they’re often seen as ‘Frankenfoods’. And their wish for Big Food to scale up their products could be seen as enabling corporate control.

Finally, Sustainable Intensifiers mirror the technophilia and land-sparing support of Technovegans, but champion innovations in farming rather than food manufacturing. The focus is first on maximising yield, and then on minimising climate impacts, using agtech solutions like genetic modification, marker-assisted breeding, and remote sensing to predict yields and precisely dose pesticides, irrigation and fertilisers.

This group thinks wealthy countries have a duty to feed the world, and promote the export of cheaply produced grains, dairy and meat to global consumers. Sustainable Intensifiers are okay with farming subsidies if they go towards yields, and promote a switch to “more efficient” livestock (like chicken over beef). But this cohort is split into two: those with strong eco credentials, and ‘true intensifiers’ primarily concerned with intensifying production with sustainability as a secondary goal.

Alliances between worldviews can lead to progress

Very few people will fit neatly into a single category, and the report suggests an alliance between certain worldviews could drive forward environmental progress (though one such collaboration might lead to negative outcomes).

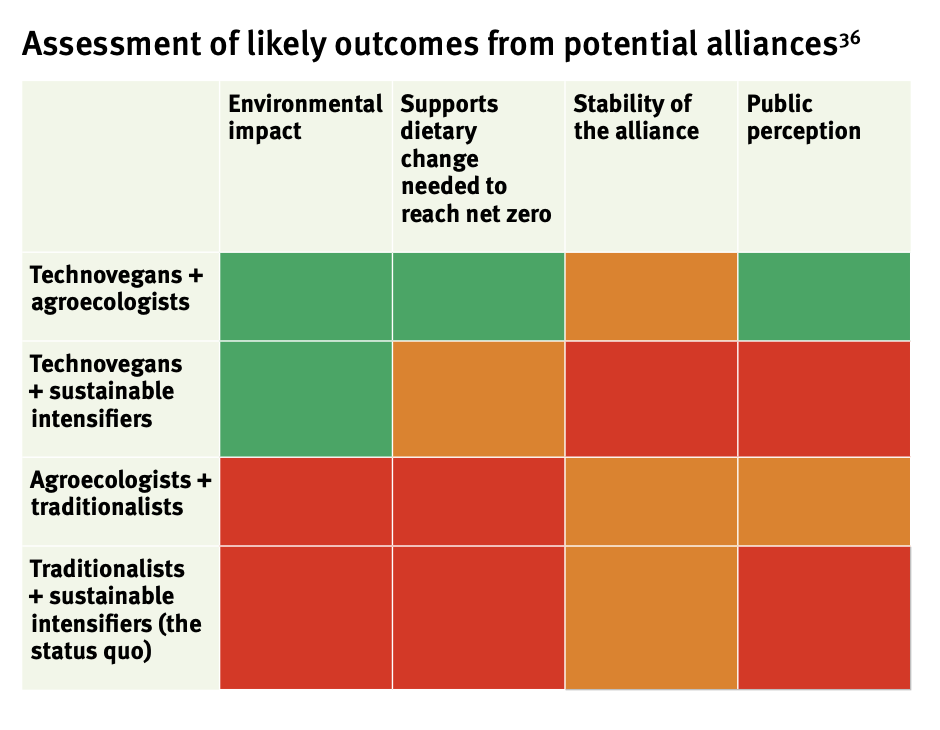

The first progressive alliance is between Technovegans and Agroecologists, whose strength lies in mirroring each other’s weaknesses. Agroecology needs radical dietary change to be scaled up, which Technovegans can provide, while the latter needs to avoid being perceived as ‘anti-farmer’, which would be helped by joining forces with the former.

There are three potential areas of agreement: the need to reduce meat and dairy consumption, restoring nature in a culturally sensitive way, and a shared enemy in the industrial meat lobby. However, there are some disputes that would need to be set aside, including the involvement of Big Meat in buying vegan companies to scale up plant-based products, and the fear that alternative protein products could displace agroecologically produced meat.

One possible solution is to encourage more diversity in the alternative protein industry and ensure that the protein transition follows a food justice approach (which could require significant policy change). “The simplest accommodation on both sides would be the understanding that, from an environmental and animal welfare perspective, ‘Big Veganism’ is preferable to the status quo of industrially farmed livestock,” the report states.

Another alliance that could bring about environmental benefits involves Technovegans and Sustainable Intensifiers, marrying their enthusiasm for food tech and land sparing. This could keep land use at low levels, especially in countries like the US, where less land is dedicated to agriculture as intensive farming is the norm.

There are some challenges here too, of course: Sustainable Intensifiers don’t believe widespread dietary change is required, suggesting intensive farming of more efficient livestock as a solution to meet increased demand, which runs counter to the worldview of the Technovegans who find animal agriculture as the most environmentally destructive activity. Plus, alt-protein products are directly competing to displace industrially farmed meat, and this partnership threatens any potential Agroecologist–Technovegan alliance – if it becomes dominant, it would be difficult to change course.

The best-case scenario is for Sustainable Intensifiers to capture the meat market that alternative proteins can’t easily replicate, like steak, while the latter could dominate the processed meat market and displace demand growth from the former, sparing more land.

However, there is one alliance that could make things worse for the environment. Agroecologists and Traditionalists are already loosely forming alliances in Southern Europe based on a shared enemy: Technovegans. Their interests lie in reducing the threat posed by the industrialisation of alt-proteins to keep demand for meet high, emphasising the role of livestock in rural culture and diet, and being sceptical of non-traditional foods or farming methods.

Why collaboration is vital among polarisation

The Green Alliance outlines that the current trajectory of food, agriculture and land use is not sustainable, and business as usual would result in the worst outcomes for all four worldviews, including for the Traditionalists, as well as make it impossible to meet climate goals.

To illustrate its point, the report takes the example of the Netherlands, whose government’s failure to tackle nitrogen pollution led to a 2019 court case that forced it to take drastic action; Italy, which has banned cultivated meat in the interest of protecting food heritage and health; and the UK, whose prime minister Rishi Sunak has rallied against an imaginary meat tax.

“Polarised debates between different approaches to the future of food production and agriculture are leading to paralysis,” reads the report. “At present, the four worldviews we have characterised here are, mostly, uncompromising… Finding common ground between these different perspectives could provide a route forward.”

The study shows that the “current impasse in food and land use policy is pernicious, arising from a superficial agreement about goals which disguises deep division amongst people who hold very different worldviews”. Experts, advocates and philanthropists looking to make progress should explore ways to create alliances between these different worldviews to bring change, instead of focusing on promoting their ideal food and land systems individually.