Europe Should Go ‘Demitarian’ To Halve Nitrogen Pollution From Agriculture, Say UN Scientists

7 Mins Read

Reducing meat and dairy consumption, food waste and fertiliser use can halve nitrogen pollution from agriculture in Europe, which is linked to biodiversity loss, respiratory and heart conditions, and ozone depletion, according to a new report commissioned by the UN.

Since COP28, there has been an even more heightened focus on gases like carbon dioxide and methane than usual – and rightly so – given their hugely detrimental effects on the climate. But one that hasn’t been talked about as much as it should have is nitrogen, a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than carbon.

Unlike methane, which is 28 times more potent but only lasts in the atmosphere for about 12 years, nitrogen hangs around for over 100 years, with different forms of the gas presenting adverse effects. Take nitrogen fertilisers, for example, which are responsible for 5% of all GHG emissions – one study suggests increasing nitrogen-use efficiency is the “single most effective strategy to reduce emissions”.

How can we do that? A new report by the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), the EU Commission, Copenhagen Business School and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) of the Netherlands – points the finger at agriculture and food systems. Called Appetite for Change, the study was conducted on behalf of the UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution’s Task Force on Reactive Nitrogen.

Focusing on Europe, it provides a ‘recipe’ to halve overall nitrogen waste by 2030, an ambition set by the UN Colombo Declaration and extended by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The key, it says, is replacing meat and dairy with plant-based foods, cutting food waste, and using fertilisers more efficiently.

The trouble with nitrogen and EU meat consumption

Globally, unreactive nitrogen forms 78% of the Earth’s atmosphere and is benign. However, the remaining reactive nitrogen can be a damaging pollutant in various forms. This includes ammonia, produced by livestock and fertilised fields and causing biodiversity loss; nitrogen oxide, which comes from fossil fuel combustion and fertilisation; nitrous oxide, which contributes to ozone layer depletion; and nitrates, sourced from chemical fertilisers and manure, which pollutes water bodies and threatens aquatic and human life.

In fact, when ammonia is combined with other gases like nitrogen oxide, it generates fine particulate matter in the atmosphere, which can exacerbate respiratory and heart diseases, in turn leading to millions of premature deaths.

As of 2015, the EU food system’s nitrogen use efficiency was at only 18%, with the rest being wasted and leaked into soil, water and air, which presents health and climate threats. This is due to inefficiencies in farms, retail and wastewater practices. Appetite for Change builds upon the UKCEH’s Nitrogen on the Table report from 2014, which noted that Europe’s food system – especially livestock – accounts for 80% of its nitrogen emissions.

The researchers analysed 144 different scenarios, involving various reductions in meat and dairy intakes, agricultural and retail practices, and wastewater treatment. Through these, they considered the health and environmental benefits, as well as the severity and costs of potential mitigation measures. They found that a “combination of halved meat and dairy consumption with improved farm and food chain management, and reduction of excess energy and protein intake achieves 49% reduction in nitrogen losses”.

This is in line with another study earlier this year that suggested swapping half our meat and dairy consumption with plant-based alternatives could double the climate benefits, halve ecosystem decline and halt deforestation. The UN report also revealed that a complete exclusion of meat and dairy from human diets – combined with “ambitious technical measures” – could lead to food system nitrogen use efficiency of close to 50%, and decrease nitrogen waste by up to 84%.

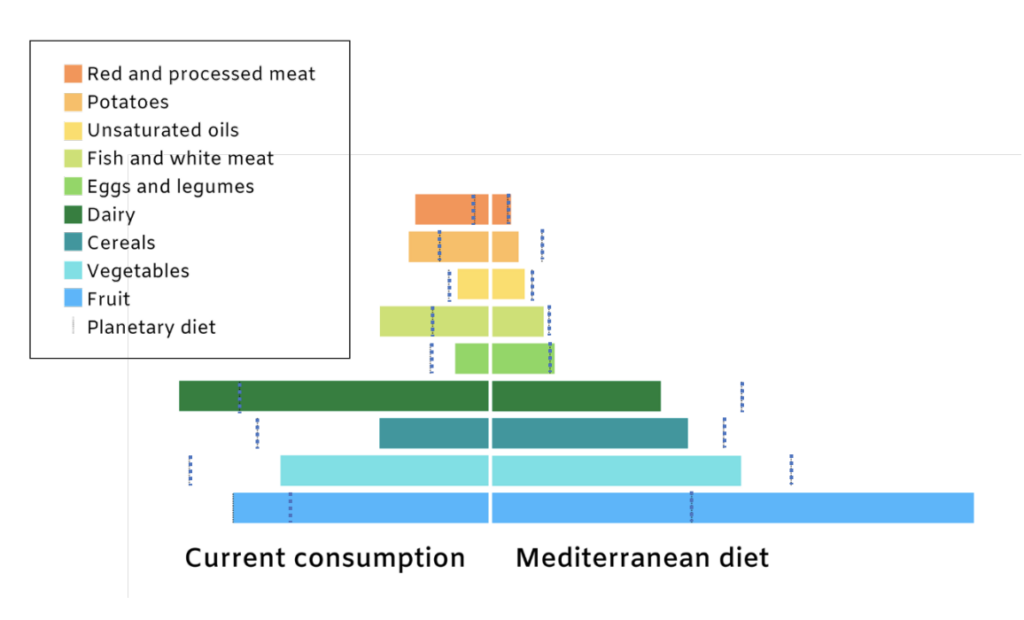

It makes sense when you realise that Europeans eat 1.4kg of meat each week, which is 80% higher than the global average, and alongside Central Asia, the region’s red meat consumption is four times the recommended daily intake by scientists and organisations like the Eat-Lancet Commission. Moreover, 40% of farmland in Europe produces feed for livestock, while meat production in the EU is set to grow until 2030.

How plant-based diets could fix the EU’s nitrogen problem

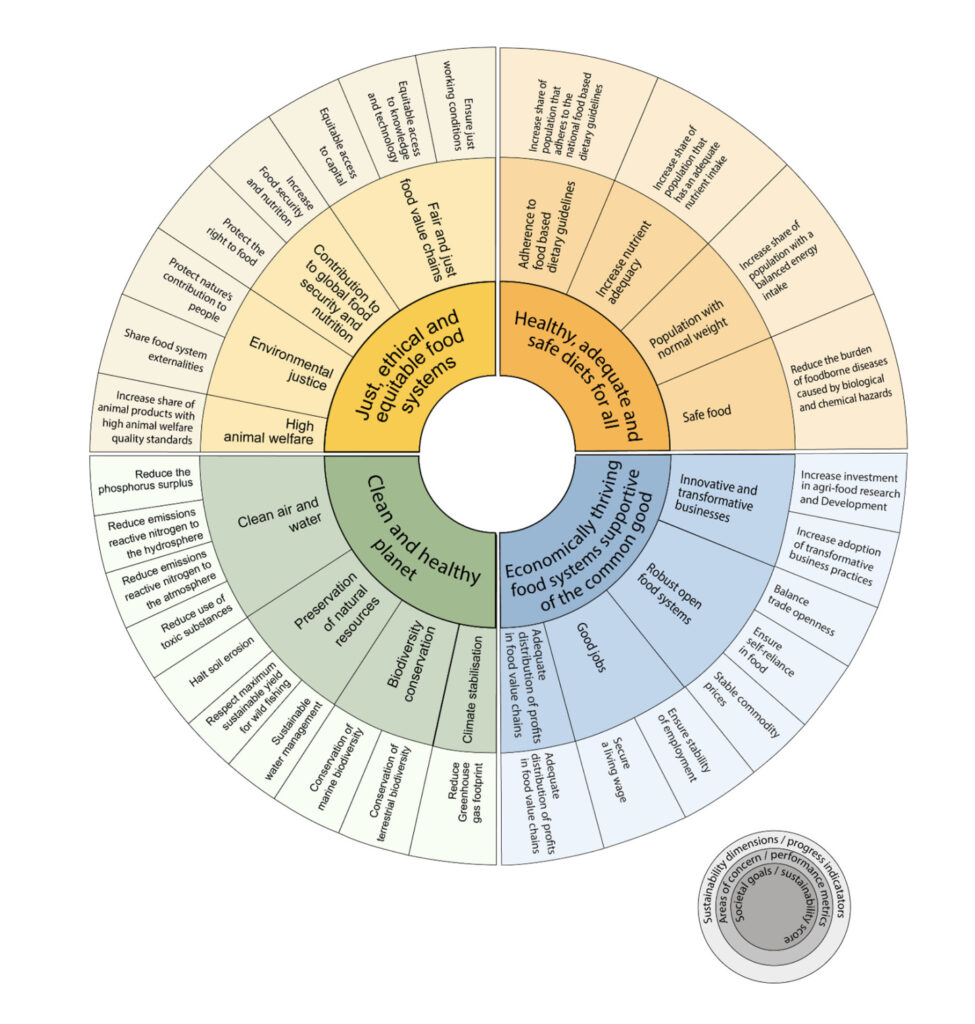

The researchers suggest a combination of interventions for dietary change, in tandem with policy evaluations of their effectiveness, to “improve nitrogen management in agriculture, reduce food waste, explore ways to recover nitrogen from organic residues, reduce the share of animal products in diets and enable a shift to a balanced and healthy diet”.

This includes the adoption of agroecological approaches and high-tech food production systems (like vertical or indoor farming), which promise enhancements in sustainability and nutrient and water use, seasonal plant-based food supply in urban areas, as well as reduced land requirements. Increasing the production of legumes – adept at nitrogen fixation – is another key measure, just as it’s important to invest in “novel and future foods” like cultured meat and precision-fermented proteins.

Such foods are valuable sources of human nutrition, use fewer land resources, and produce lower GHG emissions than animal-based food. But the report cautions that while many of these future foods are on the market, widespread adoption would mean overcoming technological, economic, legislative and socio-cultural barriers. “As such, recognising and understanding the potential of future foods in providing environmental and nutritional benefits can encourage opportunities and innovations across the food system to address the overconsumption of conventional animal-based foods in the EU,” the authors state.

Policy interventions are key here. Appetite for Change highlights taxes and subsidies as “powerful market-based instruments”. Between 2014 and 2020, meat and dairy farmers in the EU received 1,200 times more public funding than alternative protein companies. In fact, cattle farmers receive half of their income directly through EU subsidies.

The UN report suggests that meat and dairy taxes to prevent overconsumption of unsustainable foods, combined with a shift in subsidies towards low-impact foods (like plant-based) to “reduce the regressive effect of these instruments”. In addition, behavioural policies support consumers’ active and conscious choices, and nudge them into picking healthier and more sustainable foods – for example, by changing the position of food products on grocery shelves, or reducing food portions.

In addition, the researchers found that national food and nutrition policies could integrate sustainability goals and reflect the importance of low-carbon (or, in this case, -nitrogen) eating. We’re already seeing this in some quarters, with EU member state Denmark becoming the world’s first country to publish a national action plan detailing a transition towards plant-based diets. The Netherlands – whose nitrogen emission plan sparked backlash from livestock farmers – has proposed a six-year master plan to increase plant protein production and consumption, while Germany’s National Nutrition Strategy involves a focus on plant-based diets too.

“Effective strategies to food system governance must integrate a combination of such measures and target environmental, social and economic objectives at all food system stages,” states the report.

The need for a holistic approach

A plant-based transition would require less land and fewer mineral fertilisers – the prices of which, alongside energy and food, have gone up exponentially since 2021 – which will reduce energy dependency and increase resilience to the global food crisis.

More efficient fertiliser application and manure storage are key, as is better wastewater treatment to capture nitrogen from sewage (this would cut emissions and allow farmers to use recycled nutrients on fields). Switching from mineral to organic fertilisers will generate energy savings too.

The authors state that farmers, industry, government and consumers need to be mobilised and work together to reduce nitrogen losses throughout the food system – one way to do this could be by setting up governance platforms at national, regional and local levels. “Action does not begin and end at the farm gate; it requires a holistic approach involving not only farmers but policymakers, retailers, water companies and individuals,” noted Professor Mark Sutton, one of the report’s editors.

“It is also not saying we should all become vegan,” he added. “Our analysis finds that a broad package of actions including a demitarian approach (halving meat and dairy consumption) scored most highly in looking to halve nitrogen waste by 2030.”

“Freeing up land to restore habitats would help tackle the climate and biodiversity crises,” said Dr Adrian Leip, an environmental scientist at the EU Commission and lead editor of the report. “The unprecedented rise of energy, fertiliser and food prices since 2021 underlines the need to address the vulnerability of the current food system. Plant-based diets require less land and fertilisers, reduce energy use and increase our resilience to the current multi-crises: food, energy, climate.”

This UN-commissioned study comes a couple of weeks after another report (directly from the UNEP) promoted alternative proteins as a way to slash emissions, reduce biodiversity loss, pollution and deforestation,