London’s Six Airports Make It the World’s Worst City for Air Pollution from Flights

5 Mins Read

With six airports belonging to London, the UK capital is the city most exposed to air pollution from aviation globally, while Dubai International is the worst airport for climate impact.

Months after all the hullabaloo of the first transatlantic flight using only sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), it has emerged that London – with six airports to its name – is the world’s worst-polluted city from aviation.

This is according to the 2024 Airport Tracker, produced by the global think tank ODI in collaboration with Transport & Environment. The data measures the carbon impact of passenger flights and air freight, covering the emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from 1,300 airports internationally.

It found that in 2019 (the most recently available data), London’s six airports generated 27 million tonnes of CO2, 8,900 tonnes of NOx, and 83 tonnes of PM2.5 – that’s the same amount of air pollution emitted by 3.23 million cars. Heathrow, the city’s main airport, alone produced 19.1 million tonnes of carbon and 5,844 tonnes of NOx, making it the second-most polluting airport in the world.

Top of that list is Dubai International in the UAE, which hosted last year’s COP28 conference. The airport’s emissions were equivalent to those of five coal plants, with the highest amount of carbon (20.1 million tonnes), nitrous oxide (7,531 tonnes), and fine particulate matter (71 tonnes) pollution globally.

The aviation sector needs to close the decarbonisation gap

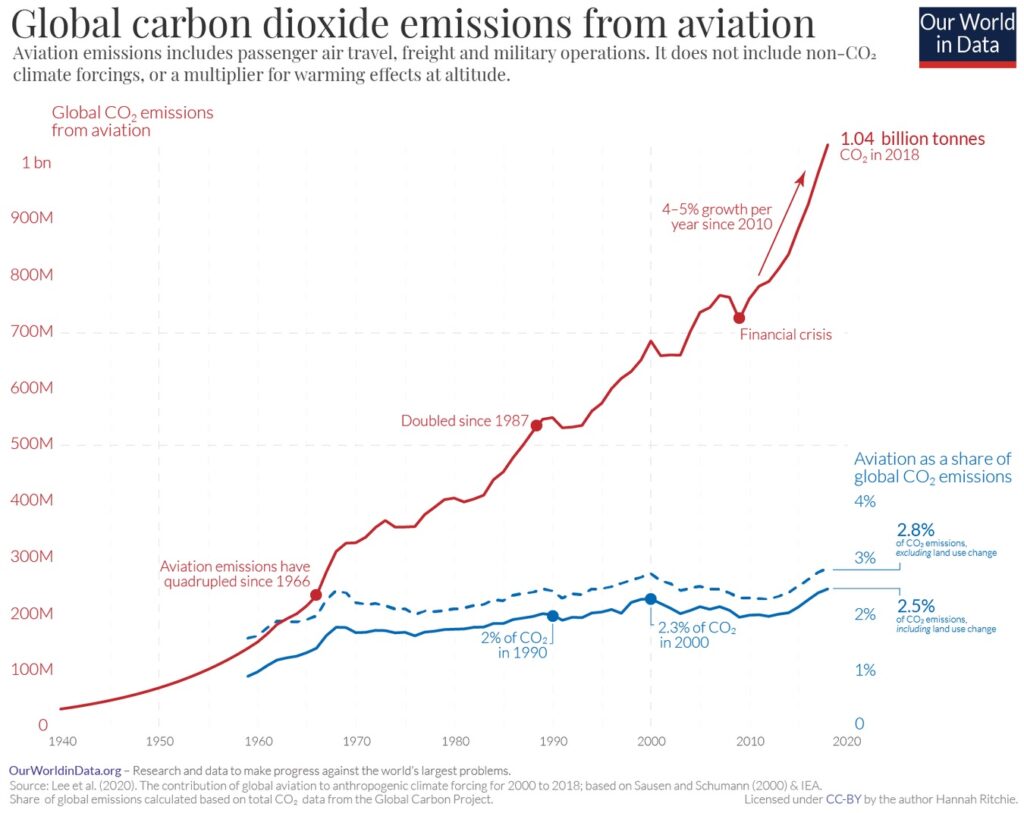

Estimates suggest that the aviation sector accounts for between 4.4 and 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions (including carbon dioxide). These numbers have doubled since 1987, and grown by 4-5% every year since 2010.

The 2024 Airport Tracker shines a light on airports, revealing that the 20 largest airports in the world collectively produced as many emissions as 58 coal-fired power stations in 2019. And in terms of cities affected most by air pollution from aviation, Tokyo is sandwiched between London and Dubai at the top of the list.

Purely in terms of carbon emissions, apart from Heathrow and Dubai, the top 10 airports with the highest footprint are Los Angeles, Hong Kong, John F Kennedy (New York), Incheon (Seoul), Charles de Gaulle (Paris), Frankfurt, Pudong (Shanghai), and Changi (Singapore).

The report revealed that current reporting standards focus on the climate impact of airport terminals and ground operations, but ignore the impact of flight emissions on airports, which is much larger. This creates three problems: airports can obfuscate their contribution to the climate crisis and local air pollution; emissions reduction efforts are centred around important, but much lower-impact aspects (like running terminals on renewable energy); and airports can paradoxically claim carbon neutrality by purchasing offsets.

“Airports are long-term infrastructure, so choices now affect climate and air quality far into the future,” said Sam Pickard, a research associate at ODI. “More has to be done to recognise these impacts and limit expansion in many parts of the world.”

Magdalena Heuwieser, press officer at activist Stay Grounded, noted that aircraft noise levels are continuously exceeded, and EU standards are completely lacking on ultrafine particles, which are a major health hazard. “Some key measures must be taken immediately to protect the health of workers and communities surrounding airports – like night flight bans or simple jet fuel improvements to have at least the same standards as car fuel,” she said.

“This research shows the gaps in decarbonising aviation,” said Shandelle Steadman, senior research officer at ODI. “Airports aren’t reporting these emissions and often slip under the radar, but without tackling localised emissions at the airport level, the sector’s climate and health impact will only worsen; damaging our health, livelihoods and climate.”

The problem with sustainable aviation fuels

Globally, air pollution is considered to be the fourth-largest risk factor for human health and early death, contributing to the two leading causes of death worldwide: heart disease and stroke. In 2019 alone, it killed 6.7 million people, and the year before, it cost the European economy £166B ($210B).

“Pollution around airports is growing year on year,” said Jo Dardenne, aviation director at Transport & Environment. “It affects millions of people, who breathe in toxic emissions and develop health conditions as a result, yet policymakers are brushing the problem under the carpet.”

The research also highlighted the challenges of using SAF. In December, industry stakeholders and government officials from the UK hailed SAF as a game-changer for the aviation sector, after Virgin Atlantic operated the first transatlantic flight using 100% SAF. There was a lot of noise around it, considering that UK prime minister Rishi Sunak had (incorrectly) called it a net-zero flight.

US government guidelines state that SAFs must emit at least 50% less carbon than petroleum-based fuels. While the Virgin Atlantic flight – which was made from 88% waste fats (including from tallow) and corn sidestreams – was said to cut life-cycle emissions by 70%, the issue is with the supply. SAFs account for only 0.1% of all jet fuel used worldwide, and it’s three to five times more expensive to produce. Despite annual production tripling from 2021-22 to reach 300 million litres, it would need to reach 400 billion litres (over 1600 times more) by 2050 to allow the industry to decarbonise.

“The small starting base, cost differential, competition with other sectors and rate of scaleup required make it unlikely that SAFs will be available in the quantities needed to sufficiently substitute for fossil fuels to achieve meaningful emissions reductions,” the report suggests.

Moreover, some experts have questioned whether SAFs are truly sustainable. Dr Guy Gratton, associate aviation and environment professor at Cranfield University, told the BBC: “We can’t produce a majority of our fuel requirements this way because we just don’t have the feedstocks. And even if you do, these fuels are not true ‘net zeros’.”

Buying carbon offsets won’t help, either. To cut back on your personal impact, one study suggests you should eat less meat, noting that swapping 30% of beef, pork and chicken with whole foods and plant-based analogues from Impossible Foods (against a 2021 baseline) could save 728 million tons of CO2e annually, which is equal to nearly all global emissions from the aviation industry in 2022.

But really, until there are better tech solutions, there’s only one thing you can do – as Cait Hewitt, policy director of campaign group Aviation Environment Federation, puts it: “Fly less.”

“Exponential growth of the sector and airports is incompatible with their climate goals, especially considering the slow uptake of clean technologies,” said Dardenne. “The sector led us to believe that they would bounce back better after the pandemic. They’ve certainly bounced back – but without action, the sector’s climate and health impact isn’t going to get any better.”