Cutting Out Meat Twice a Week Can Offset Almost All Your GHG Emissions from Flights: Report

10 Mins Read

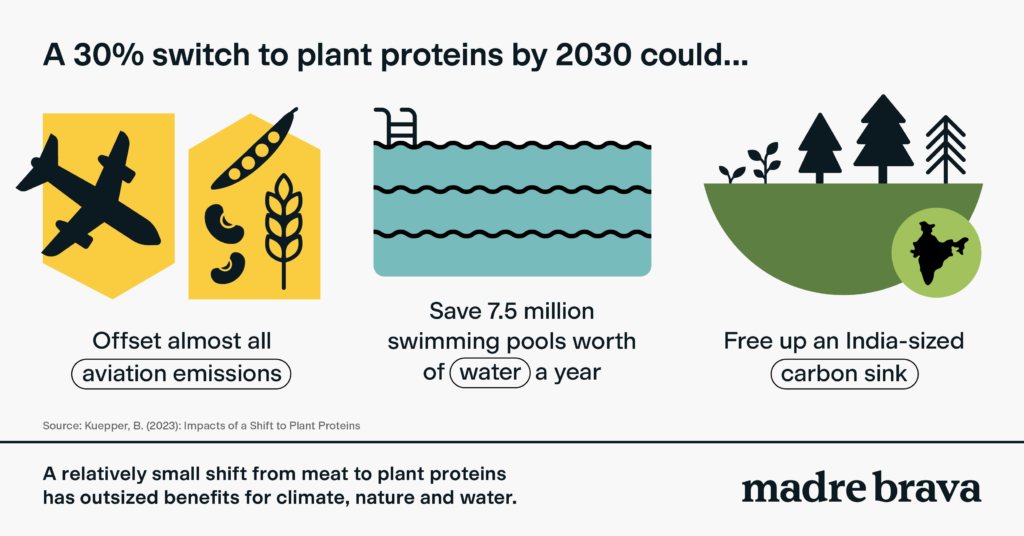

Replacing 30% of meat consumption with plant-based alternatives could offset almost all of global aviation emissions, free up a carbon sink the size of India, and save all the cows alive in the US today, according to a new report by Profundo.

“The benefits of a modest switch to plant proteins are huge,” says Nico Muzi, managing director of Madre Brava, who commissioned the report by Profundo. “The current food system incentivises producing and selling huge amounts of industrial meat, rather than more sustainable, healthier proteins. We need to turn the tide for our health and the health of our planet.”

His words come following the study’s findings that a small switch (30%) in the consumption of beef, pork and chicken with whole foods and plant-based analogues from Impossible Foods (against a 2021 baseline) could save 728 million tons of CO2e annually, which is equal to nearly all global emissions from the aviation industry last year.

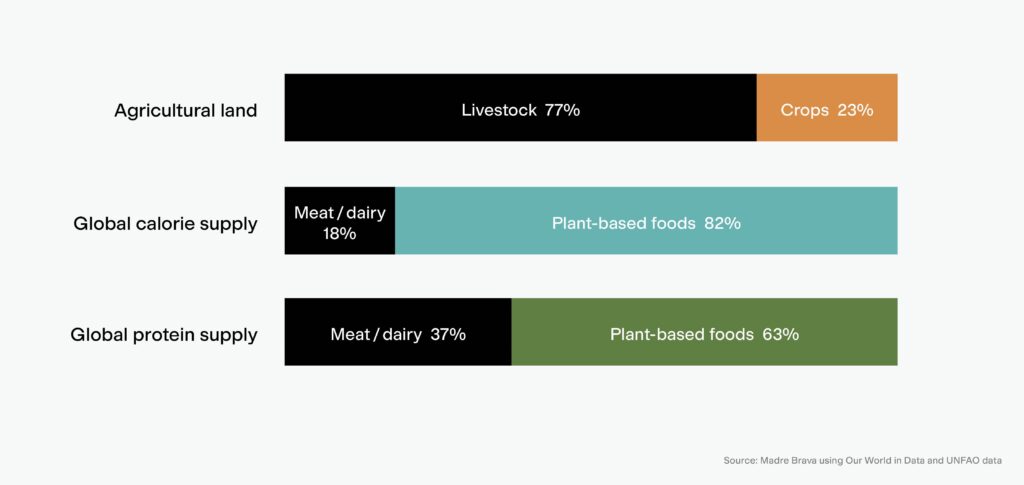

Over three-quarters (77%) of the world’s habitable land is used for animal agriculture. Cutting just under a third of our meat consumption would free up 3.4 million sq km of farmland – which is an area bigger than India – and restore it to nature to boost biodiversity and absorb carbon emissions. In addition, the report highlights the high water footprint of livestock farming, with the 30% switch saving 18.9 cubic km of water, equivalent to 7.5 million Olympic-sized swimming pools per year.

And it’s not just the environment, of course. Doing so would help save 420 million pigs, over 22 billion chickens and 100 million cows, which would be the same as sparing all cows alive in the US today.

“A 30% reduction in meat is in line with the widely shared goal of a global 50% reduction by 2040,” says Muzi. “While this goal is global, the exact meat reduction targets will need to be tailored to specific regions or countries based on the relative consumption and emissions.”

The report chimes with similar research published last month, which found that swapping 50% of meat and dairy for plant-based alternatives could reduce agricultural and land-use emissions by 31%, halt deforestation and double overall climate benefits.

North America leads red meat consumption, followed by Europe and South America

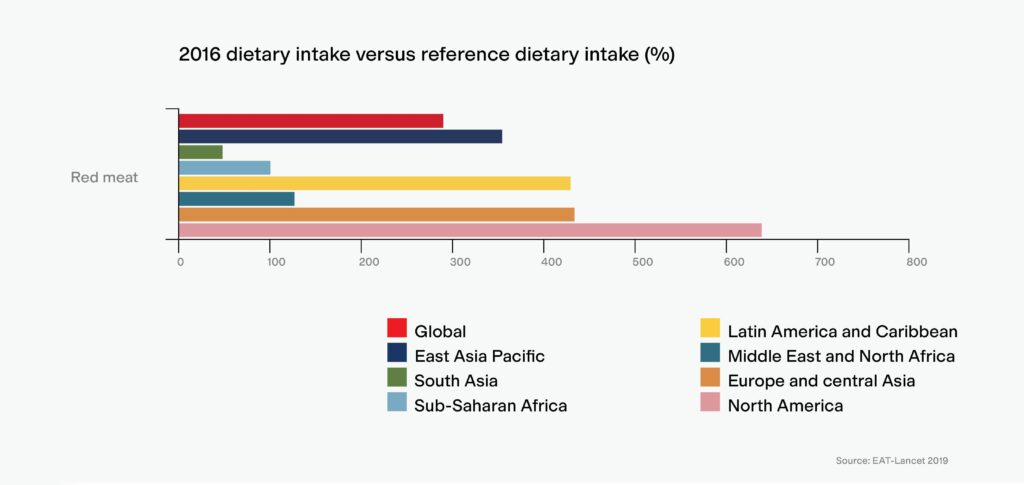

The proposed 30% shift model only applies to countries where meat consumption is higher than the recommended daily intake by scientists and organisations like the Eat-Lancet Commission. Profundo’s analysis of Eat-Lancet data found that Americans eat over six times more red meat than advised by the commission – by far the higher of all other regions.

There are two main issues here, according to Muzi. The first is the severe underreporting of the “climate-meat nexus” in US media – a Faunalytics report found that only 7% of all climate stories mention animal agriculture. “It’s hard for the public to know about the oversized role of meat in driving climate change if they are not informed about it,” he says. That perhaps explains why 40% of Americans don’t believe eating less red meat would help climate change, a number that rises to 74% for overall meat consumption according to a separate study.

The other problem is the power of the meat lobby. Livestock farming receives 800 times more funding than plant-based companies in the US, according to a study that suggests the “gigantic power” of the meat and dairy lobby is blocking the rise of sustainable alternatives. “There is a well-funded communications machine coming from the meat and dairy industry to promote the sustainability of livestock, and even to push misinformation,” says Muzi.

“Borrowing heavily from the playbook of the oil industry, media reporting and exposés have shown that big meat processors and dairy corporations use their abundant financial resources to manipulate the facts and sow doubts about climate science on animal products,” he adds, pointing to research revealing that the 10 largest livestock companies in the US “have contributed to research that minimises the link between animal agriculture and climate change”.

North America is followed by Europe and Latin American countries Argentina and Brazil, which eat more than four times the recommended amount of red meat. So even with a 30% switch to plant-based alternatives, people will still be able to consume more red meat than is advised.

Overall, meat consumption has increased globally in the past few decades, with high intakes concentrated in a few regions, according to the study. The US, Australia, Argentina and Brazil accounted for over 100kg of meat eaten per capita each year, as opposed to an average of 75kg in the EU and the UK, and less than 5kg in India, Bangladesh or Burundi.

Meat consumption is set to increase

In the sea of reports outlining the graveness of continued meat-eating rates, counter research by the livestock lobby, and consumer confusion from contradictory research and misinformation, meat consumption already rose by 19% from 2011-21. Now, an ever-growing global population, higher incomes in developing economies, and better life expectancy rates to a further rise in meat intake, according to Profundo.

According to the OECD-FAO, global poultry consumption is set to increase by 15% by 2032, with pork consumption expected to grow by 11% and beef by 10%. Profundo stresses that the only way to achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goals is to reduce industrial meat consumption and production. Strategies to address this have included reducing livestock’s emissions intensity by, for example, changing the digestive fermentation process in methane-producing ruminant animals.

But these measures don’t do much. “Even the most optimistic estimates of emissions reductions from intensification and efficiency measures are not enough to bring protein production in line with climate goals. As such, structural solutions focused on making sustainable proteins the cheapest, easiest choice for consumers are critical,” explains Muzi.

“Greater attention needs to be paid to a protein transition, alongside exploring sustainable intensification and methane mitigation technologies,” he adds. How can we do so? “We need to incentivise these products by ensuring they are as cheap, healthy, and convenient as industrial meat products. To do that, we need to level the playing field between animal-based and plant-based products in terms of public and private sector support.”

Muzi continues: “For example, in most countries around the world, meat and dairy production is heavily subsidised and receives public funding for promotion and advertising. In some cases, value-added tax is higher for plant-based foods than it is for meat and dairy products by an order of magnitude.”

He points to how public investment in alt-protein R&D is “significantly lower” (97% in the EU and 95% in the US) than it is for livestock. “Such policy choices run counter to all corporate and governmental efforts made to reverse the triple crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and water scarcity.”

Going meatless twice a week in the EU & UK has tremendous benefits

If people stop eating meat for two days a week – “Meatless Mondays… and Tuesdays”, as Profundo puts it – in the UK and EU, replacing it with a mix of whole foods and vegan analogues, it could wave 81 million tons of CO2e. This is the same as removing about a quarter (65 million) of all cars in the UK and EU. Doing so would free up land larger than the UK and save 2.2 cubic km of water – or 880,000 swimming pools worth of water per year.

The problem, however, is that Europeans eat 1.4kg of meat each week, which is 80% higher than the global average. Factory farming plays a big role in the region’s emissions, over a third (36%) of which are linked to food, with animal products accounting for 70% of this. Alongside dairy, meat production in the EU – which is set to grow until 2030 – is the single largest source of methane emissions.

Muzi outlines how it’s not just meat-eating that needs to be reduced. Dairy is a massive issue too, and cutting down its intake is necessary to “achieve climate stability” and will be key to ensuring “food security for a growing global population, protection for biodiversity, water availability, reduced air pollution, human health improvements, and better animal welfare”.

“Part of our theory of change is that reducing total beef production and consumption will also support reducing production and consumption of dairy since the industries are linked,” he notes. “For example, in the US and the EU, a major portion of beef – particularly for low-quality meat – comes from dairy cows. As such, driving down demand for beef will reduce the offtake demand for dairy cattle, and impact the profitability of the dairy industry.”

And while a 30% reduction will still mean Europeans will eat more meat than recommended, “it’s in line with a progressive reduction in the decades to come to achieve net-zero by 2050 in the EU”.

Big Food has a big role to play

The report looked at the role of meat producers, foodservice giants and retailers in meat consumption too. In 2021, Cargill, Tyson, JBS and National Beef Packing alone controlled between 55-85% of the beef, pork and chicken markets in the US. The top 20 meat producers account for 15% of the global slaughtering of cattle, chickens and pigs.

But a 30% reduction in the production of meat from these animals by these companies could result in a reduction of 150 million tons of CO2e – nearly the annual GFG emissions of the Netherlands. Moreover, about a million sq km of land would be freed, and 3.6 cubic km of water would be saved.

In terms of retailers and foodservice companies like Carrefour, Lidl, Tesco, Ahold Delhaize, CP All and Sodexo, substituting half of all meat sales with plant-based foods like tofu, pulses, mycoprotein or fermentation-based alternatives could save 31.6 million tons of CO2e, 102,000 sq km of land, and 0.67 cubic km of water.

Meanwhile, a 50% substitution of beef sales at McDonald’s, which is responsible for 1.5% of global annual beef production, with a mix of alt-proteins would save 15 million tons of CO2e (the equivalent of the annual emissions of Slovenia), free up 84,000 sq km of land (equalling the surface area of Austria), and conserve 0.2 cubic km of water (over 80,000 swimming pools’ worth).

But a big problem with meat companies is aggressive political lobbying to thwart the alt-protein sector, as evidenced by recent investigations into the effect of the animal agriculture lobby on work by the UN FAO and the EU. Muzi cites research uncovering how “taken as a share of each company’s total revenue over those time periods [2000-18], Tyson has spent more than double what Exxon has on political campaigns and 21% more on lobbying.”

Switching from meat to plant-based could produce 14 times more protein

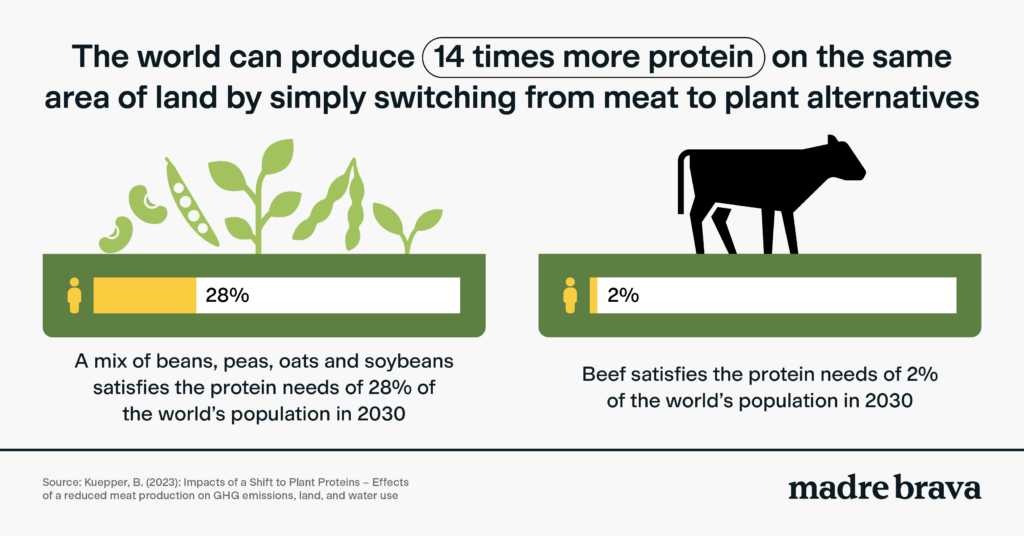

Profundo modelled two uses of farmland to find out how protein production could be impacted by a moderate shift from animal-derived to plant-based meat: it assessed the production of beef and a mix of brands, oats, peas and soybeans.

The report found that the same area of land can yield enough beef to satisfy the needs of 2% of the global population as it can produce plant protein crops that could satisfy 28% of the world. It aligns with similar research that revealed how 63% of the world’s total protein supply comes from plant-based food.

As some cattle-rearing land is unsuitable for crop cultivation (like pastures in hilly areas), the shift from beef to plant proteins could additionally free up 1.3 million sq km of land, an area the size of France, Germany and Italy combined, which can help absorb carbon and boost biodiversity.

“Meat is a very inefficient way of producing cheap unsustainable proteins for a growing world population,” says Muzi. “For food security reasons, world leaders should be looking at boosting the production of protein crops and reducing the production of beef.”

He posits public procurement in schools as an example: “Governments can ensure plant-based proteins are offered to schools to help students understand healthy diets, and reduce consumption of high processed foods high in fat, sugar, and sodium. In many cases, plant-based offerings can also be cheaper to support the high volume needs of public schooling.”

Some companies are coming up with blended and hybrid meat products, mixing conventional meat with vegetables or plant-based alternatives. Could these innovations help drive the transition? Definitely, says Muzi: “Blended products are an important way of introducing plant-based and alternative proteins without having to introduce entirely new products. Ultimately, we want meat eaters to reduce their meat consumption,” he adds. “Ideally, blends are a gateway for dedicated meat-eaters to increasingly reduce their meat consumption and move towards more sustainable diets.”

Muzi touches upon how people’s attitudes and choices have been shaped by the food industry for decades, and implores these corporations to encourage the selection of alt-protein. “Currently, companies and governments incentivise widespread purchasing of cheap, high-emission, unhealthy meat products through pricing, advertising, and product placement among others,” he says.

“The onus should not be put on consumers to choose these products out of their own good will – and such an approach will continue to make plant-based and alternative proteins a niche product for wealthy consumers,” Muzi adds. “Instead, we can view the issue as a systemic problem in which subsidies, taxes, public procurement and corporate strategies can shift to newly incentivised plant-based and alternative proteins.”