McDonald’s Spent 7 Years Making A Burger Better for the Palate, But Not the Planet

6 Mins Read

McDonald’s new burgers are on their way, after seven years of testing and over 50 tweaks, in response to drying consumer sentiment about its dry burgers. But while these burgers might be more impactful on your palate, they certainly leave a sour taste on the planet, as the world’s biggest food chain keeps increasing its GHG footprint while planning for net zero.

Hurray, the new Big Mac is here!

There are 50 new things for you to cheer

But our climate footprint is worse, oh dear

Meeting our net-zero goals? Nowhere near.

I wrote this jingle in celebration of McDonald’s new non-dry, less-industrial-looking burgers. The lettuce and pickles are fresher! The room temp cheese is meltier! The onions are cooked Oklahoma-style! The bun is now a brioche, and there’s more special sauce! And oh, the sesame seeds are more random so it doesn’t look like a robot placed them! Yay!

I only jest, of course. I have zero interest in commemorating a product I will never eat, but it’s hard to look past such a massive change in a core product offering by the biggest food company on the planet, which it is also consequently ruining.

The Wall Street Journal reported it took McDonald’s seven years to test different ways to make its burger better after a survey of nearly 50,000 by research firm Technomic revealed that only 29% of Americans crave it. 13th on the list and almost two times less desirable than Burger King? Not good enough, decided McDonald’s.

And so began the quest for its “best burgers ever”, which initially rolled out in Australia and New Zealand and are now coming to the US. “We can do it quick, fast and safe, but it doesn’t necessarily taste great. So, we want to incorporate quality into where we’re at,” said Chris Young, McDonald’s senior director of global menu strategy.

While a little self-reflection and honesty from the company is great, it’s lacking in this aspect when it comes to climate change. “Sometimes you have to look to the past to understand where you are going in the future,” Young added. So let’s just do that, shall we?

Ambitious McEmissions

Since 2017, when it began testing its new burgers, McDonald’s emissions have risen across Scopes 1, 2 and 3 (the latter includes emissions from across the value/supply chain). According to data the company provided to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), its emissions amounted to 44.3 million tonnes of CO2e in 2017, which is the equivalent of powering 8.6 million homes or driving 9.86 million gas-powered cars for a year.

In 2021 (the latest available data), its emissions across the three Scopes were 57.4 million tonnes of CO2e. This is the same as 11.2 million homes’ annual energy use and 12.8 million cars being driven for a year, and higher than the emissions of Greece, Peru or Israel. Compared to the 2017 baseline – the year R&D for the new Big Mac and other burgers got underway – it’s nearly a 30% increase.

That figure rise is striking, given that it’s almost the same (31%) as McDonald’s targeted emissions intensity reduction (per tonne food and packaging) across its supply chain by 2030, from a 2015 baseline. The company has additionally committed to a 36% decrease in emissions from its restaurants and offices by that year.

Also in 2021, the fast-food chain committed to net zero by 2050. But the big beef with its emissions is, well, beef. Already known as the worst-emitting food in the world – accounting for twice as many emissions as the next best on the list, and a quarter of all food emissions – industrially-reared beef makes up about 80% of McDonald’s emissions.

McDonald’s – which is responsible for the production of around 1.5% of all beef globally – has consistently maintained that it promotes ‘sustainable beef’, having helped found the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef in 2010. In its CDP disclosures, it outlines its commitment to this agenda: “We support beef production that’s environmentally sound [it doesn’t], protects animal health and welfare [it doesn’t], and improves farmer and community livelihoods [it doesn’t], and we have done for over a decade [it hasn’t].” In fact, McDonald’s only scores 16.1 out of 100 on the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark.

“This global movement is gaining extensive momentum through conversations, collaborations, pilot programs, and global and local roundtables, and is helping influence not just beef in McDonald’s supply chain, but beef production around the world,” the company adds in its CDP filings.

Looking to the future: McBlend?

As Young said, looking to the past to figure out the future is important – how can McDonald’s learn from its past? An analysis by The Mirror (using a carbon footprint calculator) shows that the Big Mac in the UK is responsible for 2.35kg of CO2 being released into the atmosphere, “with a gherkin from Turkey, lettuce from Holland or France, beef from Ireland or the UK, and mayonnaise made in Lancashire, among other ingredients”.

Of this number, the beef patties are the single-biggest culprit, emitting 2.11kg of CO2 (nearly 90% of the total footprint). This is in stark contrast to the climate impact of the vegan McPlant burger, which uses a Beyond Meat patty and only emits 0.12kg of carbon (95% less than the Big Mac).

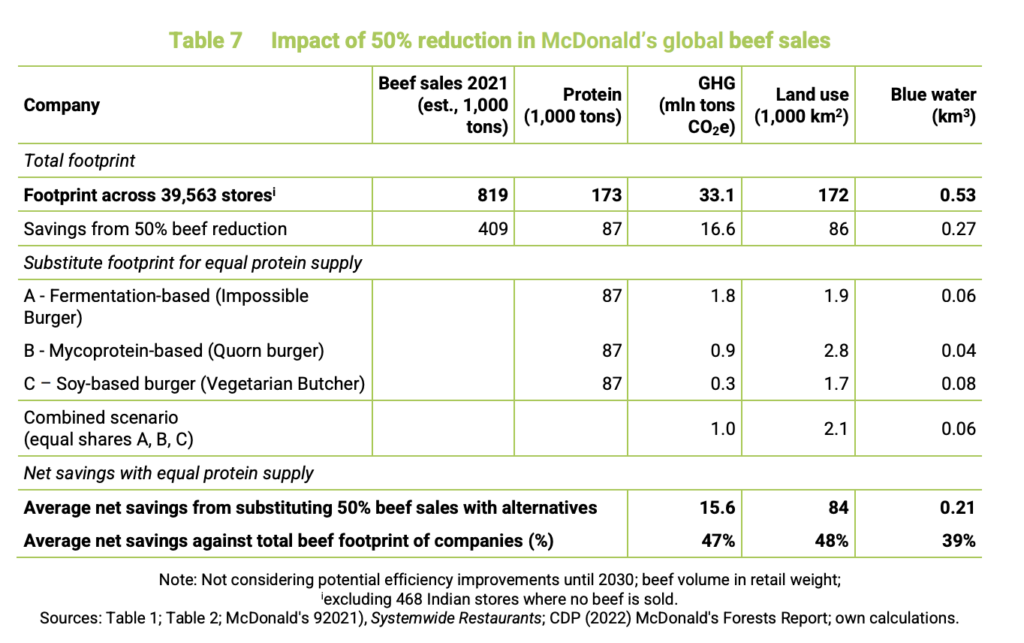

It’s probably fair to assume that a company that made its $200B fortune on beef isn’t suddenly going to turn its back on the meat – but could there be a middle ground? Research by Profundo (commissioned by Madre Brava) has floated this idea. It calculated the impact of swapping 50% of McDonald’s beef with a mix of plant-based proteins, such as fermentation-based alternatives (like Impossible Beef made of soy protein and fermented heme), mycoprotein-derived meat (like Quorn) and soy burgers (like The Vegetarian Butcher).

It revealed that subbing half of all its beef sales (which have increased by 10% between 2017 and 2022) with vegan proteins can save 15 million tons of CO2e (the equivalent of the annual emissions of Slovenia), free up 84,000 sq km of land (equalling the surface area of Austria), and conserve 0.2 cubic km of water (over 80,000 swimming pools’ worth).

Similar research by Oxford University’s Joseph Poore (on McDonald’s and Burger King) found that doing so would reduce land use by 8.5 million hectares (an area the size of Ireland), remove 17 million tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere annually for 100 years, and reduce GHG emissions by 34 million tonnes of CO2e per year – the latter two figures would make up over 80% of both food giants’ net-zero targets.

There’s merit to this method. Meat causes twice as many emissions as vegan food, and one study has revealed that switching 50% of our meat and dairy intake with plant-based alternatives can slash agricultural and land use emissions by 31%, halt deforestation and double overall climate benefits. This is also the principle validating the approach of companies making blended meat – combining animal-derived meat with plant-based proteins and ingredients.

And it’s not like McDonald’s is opposed to this approach. Take a look at its famous chicken nuggets. While a nugget would never be 100% chicken (it needs breading and binders), in the UK, chicken only makes up 45% of the McNugget, with crumbing, flavourings and wheat gluten (aka seitan) making up the rest. The amount of wheat protein may not be a lot, but it’s still a marker of success for blended meat among the masses.

There may be 50 new things with McDonald’s new burgers – less beef needs to be the 51st.