Price Parity: 6 Steps to Make Plant-Based Meats Cheaper Than Conventional Meat

7 Mins Read

With even the cheapest plant-based meat products usually more expensive than conventional protein, cost remains a key consumption barrier for vegan alternatives – a new report shows how these can reach price parity.

Plant-based meat has had a challenging year, with the higher cost of living, attitudes around ultra-processed food, and misinformation about these products contributing to dwindling sales globally.

Many studies have identified the major factors that hold consumers back from eating these products. While taste and texture are regularly cited as the main barriers, alongside health/nutrition, price is key too. Despite a spate of launches over the last few years, and advancements made in the flavour and mouthfeel department, plant-based meats still cost on average than their conventional counterparts.

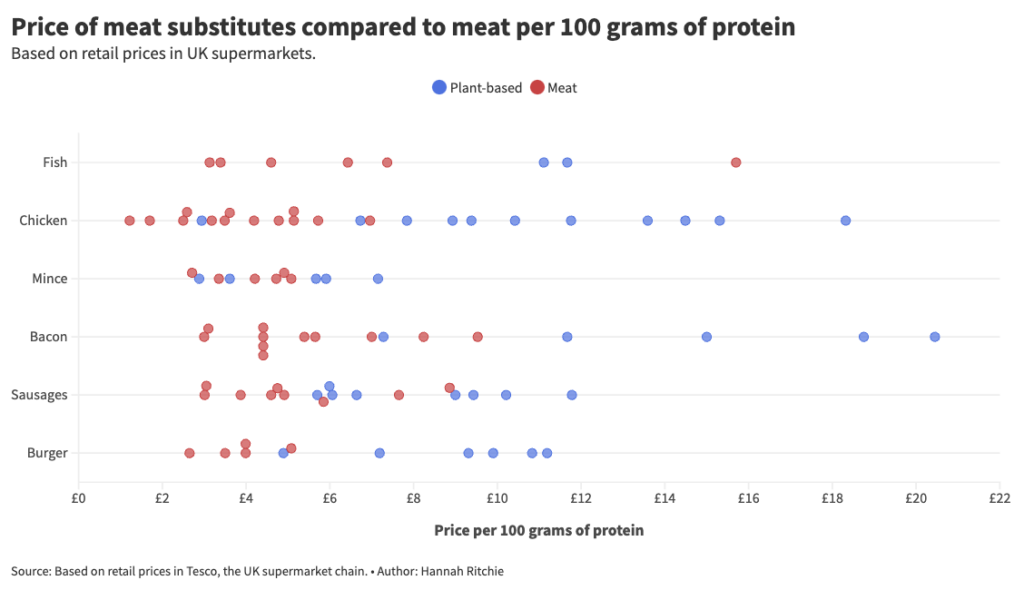

Alternative protein think tank the Good Food Institute has revealed that, in 2022, plant-based meat was 67% more expensive than animal meat. Likewise, research by data scientist Hannah Ritchie last year showed that even the cheapest plant-based meat alternatives are higher in price than animal-derived meat, suggesting that the former don’t just need to be at parity with the latter, but rather much cheaper.

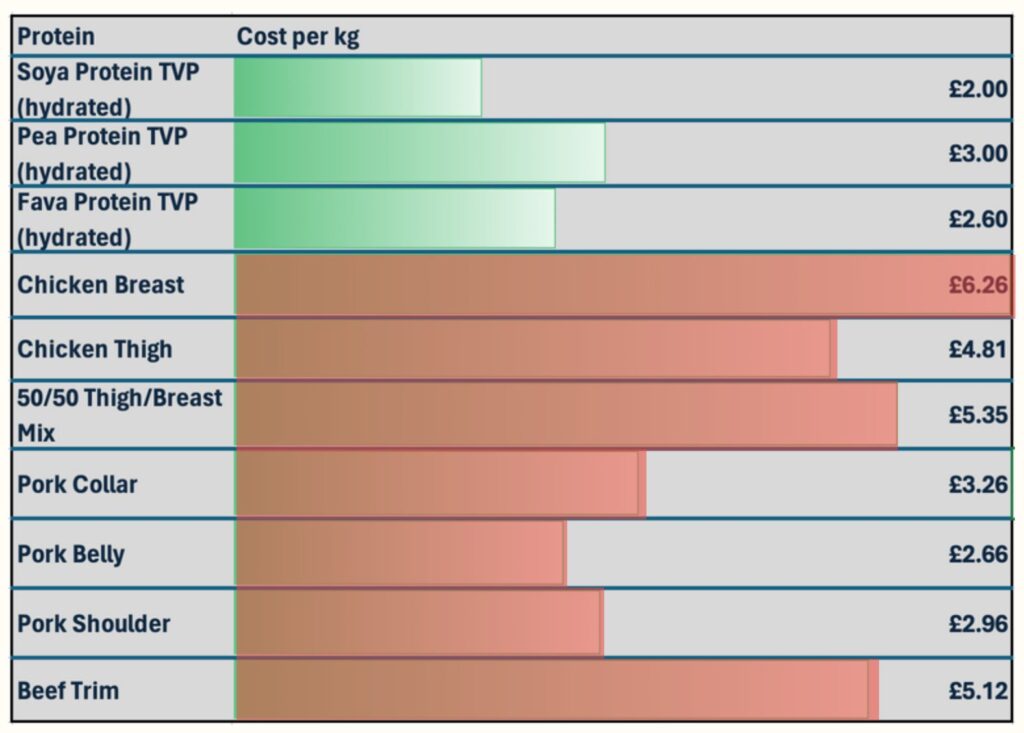

So how do we get there? A new report by British chef and writer Anthony Warner for New Food Innovation delves into solutions to make meat alternatives cheaper than they currently are. The whitepaper outlines how textured vegetable protein (TVP) is usually much cheaper than meat but, as the former is combined with a bunch of other ingredients to enhance the end product, things get a little trickier.

On average, hydrated TVP only makes up 20% of a plant-based burger’s ingredient cost. Fats and oils account for another 20%, emulsifiers and gelling agents 15%, and crumbs, seasonings, etc. 5%. But the real expense is in the flavourings to recreate the taste of beef and mask any native flavours in the plant protein, contributing to 40% of a vegan burger’s cost.

This is all before you consider the costs of processing – hydration, specialist equipment, time-consuming processes, specialist handling, efficient mixing and wastage are part of the manufacturing cycle, which can comprise up to thrice as many steps as conventional meat production.

Here’s how the plant-based meat industry can step over these hurdles and provide cheaper products to reach price parity with meat.

1) Tweak your flavour focus

A 1,000-person survey last year found that taste is the biggest deterrent for plant-based meat consumption for Brits (66%), followed closely by price (62%). Taste and texture are also the most common reasons for reducing consumption of meat analogues (40%) in the UK. Clearly, it’s a key factor to unlocking cheaper alt-meat. But as noted above, it’s the costliest too.

A typical burger formulation will have a savoury base element, a top-note meat flavour, a grill flavour, and a masking flavour. Masking is important as many plant proteins can have an unappetising taste, but using more specific masking agents can help reduce costs. Flavour companies can molecularly analyse the tasting notes in specific proteins to identify the best masking options – this targeted approach can bring savings compared to previous trial-and-error methods.

The flavour industry is dominated by a few companies, which means sometimes food manufacturers end up overpaying. A push to improve plant-based flavourings has meant higher research and marketing costs, which are often passed on to the producers, but market consolidation and sourcing flavours from a single supplier can help these meat alternatives get closer to price parity.

Another solution could be to use non-natural flavouring agents, which are cheaper and can offer a wider gamut of taste notes, especially with grilling and smoking. This comes without any “obvious penalty on labelling”, given that they can be described as ‘flavouring’ instead of ‘natural flavouring’.

2) Leverage enzymes and in-built emulsification and gelling properties

Gels and emulsifiers like methylcellulose are omnipresent in plant-based meat and have key functional attributes, but these can make up between 10-15% of the total cost. While some companies are developing alternatives to methylcellulose, these are still expensive. The report recommends enzymatic solutions – especially those based on transglutaminase – which, while needing time and heat, require low levels of dosing and achieve “considerable cost savings”.

Emulsifiers are easier to remove, but they’re rarely used in high enough proportions to significantly impact the price of the final product. However, eliminating them will obviously cut some costs, and a greater understanding of existing ingredients’ functionality can help manufacturers make use of the natural emulsification, foaming and gelling properties of plant proteins.

3) Switch the processing and prolong the shelf life

Short shelf life for chilled plant-based meats prevents long production runs and adds to wastage. The industry can learn from the bakery sector when it comes to shelf-life extension, including the use of buffered vinegars, fermented acids and natural sorbate sources.

But it’s the micro issues that are most important to tackle. Using air-classified protein concentrates – which are cheaper and much more energy-efficient – over isolates is one solution, although they can be harder to work with and would need some refinement. Many high-quality TVPs are now being made entirely from plant protein concentrates, rendering cheaper and more climate-friendly ingredients.

4) Diversify the protein type

It’s easier to create plant-based analogues of lower-value, processed meats, but more premium cuts are harder and costlier to achieve – vegan bacon being a prime example. New extrusion processes can help overcome this obstacle, with a better understanding of their impact on finished products and the development of novel processes to improve meat-like structures enabling the creation of next-gen extruded plant proteins.

Many of these processes can help produce high-quality meat structures from plant concentrates, and their focus is less on burgers and sausages, and more on chicken, beef, lamb or pork chunks, strips and pieces to be used directly in dishes like pies, ready meals and stir-fries. These cuts of meat analogues only require small modifications to existing extrusion processes, meaning they’re similar to existing TVPs in terms of price and labelling. Plus, they don’t require any gelling, emulsification or tropical fats to deliver acceptable products.

5) Valorise the sidestream to cut food waste

When a protein is concentrated, something is always left over – for example, producing a protein-rich fraction from legume flour will leave a carbohydrate- and fibre-rich fraction, and utilising this is key to making cheaper meat alternatives. This already happens in the meat and dairy industry: think whey from cheese production and rendered animal fats.

Sidestream valorisation is essential for driving down costs and competing with animal agriculture. Some carb-rich streams can be used in food production as a source of starch to thicken soups or make extruded snacks, but they can also be used as feedstock for the fermentation sector to possibly increase protein yields.

“There are several projects currently in the research stage that will help increase the utilisation of plant-based side streams, and if the market is to grow as predicted, this work is going to have to increase in urgency,” the report notes.

6) Look local to find cheaper plant protein sources

Current plant proteins are dominated by soy, pea and wheat, which often travel vast distances as part of a complex supply chain. While these still usually have environmental benefits over meat, this isn’t an ideal scenario. The research points to provenance and local sourcing as a major opportunity for plant-based meat.

For example, in the UK, fava beans are an important crop, but are mostly exported or used for animal feed. While these aren’t as easy to transform into TVP as soy or yellow pea, and come with flavour challenges, extrusion and masking tech has helped bridge this gap, with the first TVP made entirely from fava bean concentrate soon to be available to manufacturers in the country. (Beyond Meat’s reformulated beef is a case in point, adding fava beans in its new recipe.)

“There is much work to do. Some short-term solutions can produce significant results. Other approaches are likely to take more time, particularly those that require us to shift consumer understanding,” the report concludes. “But it is definitely possible that, if companies can maintain focus, a lot of plant-based products can be shifted towards price parity over the next couple of years. And if a few medium-term projects and research streams are implemented, we may even move beyond that point.”