UN Accused of Misusing Research to Underestimate Meat Industry Emissions in COP28 Study

6 Mins Read

During COP28, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released a study analysing livestock emissions – now, experts whose data was cited by the report are accusing the body of distorting their work to understate the climate impact of this sector.

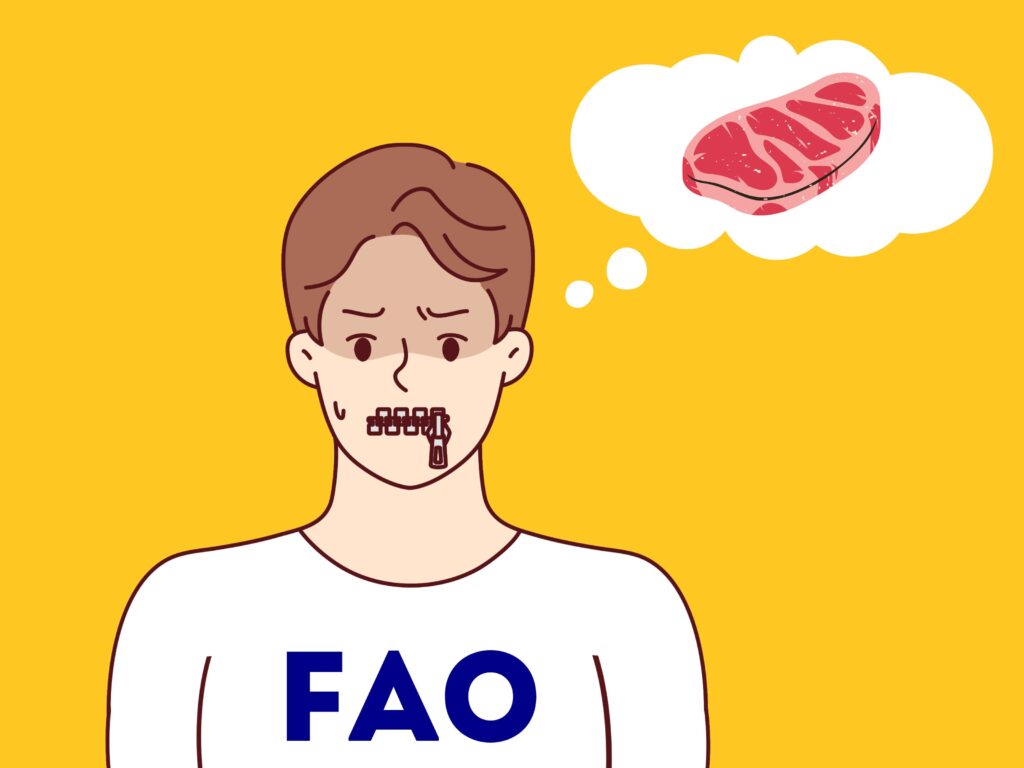

The FAO continues to feel the heat. After a year where it was found to have censored its experts’ work on reporting the true emissions of the livestock industry, and its global roadmap to 1.5°C was roundly criticised for failing to address animal agriculture, the UN food organisation is now facing accusations of misusing data to conclude that reducing livestock farming will only have a small effect on the planet.

Leiden University’s Paul Behrens and New York University’s Matthew Hayek have sent a letter to the FAO, calling for an urgent retraction of the Pathways Towards Lower Emissions report, which was launched on the sidelines of COP28 last December. They allege that the FAO “seriously distorts” the findings of their research and misrepresents the potential for dietary change to reduce food emissions.

The academics accuse the FAO of poor framing, inappropriate choice of data, and errors in methodology, and call on the UN body to re-issue the report with more appropriate sources and methodology, as its current analysis estimates an emissions reduction of reducing livestock production six to 40 times lower than the scientific consensus.

Multiple scientific studies have shown that dietary change is the best way to reduce emissions from the food system, which accounts for a third of all human-caused emissions. Of these, meat is responsible for 60%, which is twice as high as the climate impact of plant-based foods.

“The scientific consensus at the moment is that dietary shifts are the biggest leverage we have to reduce emissions and other damage caused by our food system,” Behrens told the Guardian. “But the FAO chose the roughest and most inappropriate approach to their estimates and framed it in a way that was very useful for interest groups seeking to show that plant-based diets have a small mitigation potential compared to alternatives.”

Highlighting the FAO’s ‘egregious’, ‘inappropriate’ approach

The FAO’s report was the third in a series of studies highlighting livestock emissions, and came days before it released its highly anticipated roadmap to reduce food system emissions and keep in line with the 1.5°C carbon budget. The paper reduced the UN food body’s estimate of the animal agriculture sector’s contribution to overall emissions for the third time running, and used a study by Behrens and colleagues in 2017 to state that shifting away from meat consumption will only bring down agricultural emissions by 2-5%.

Behrens’s 2017 study analysed the environmental impact of countries’ nationally recommended diets (NRDs), which have since become outdated. In Spain, the NRD guidelines recommend between 0 to three portions of meat per week (which means it has a range with no meat), while in Germany, they suggest that 75% of diets be plant-based. China has decreased recommended meat intake levels over time too. Denmark and South Korea, meanwhile, have incorporated plant-based foods into their national action plans, with the former advising a reduction in beef and lamb.

Behrens noted that most NRDs don’t take sustainability into account – they’re focused on health and nutrition, and aren’t reliable indicators of emissions mitigation potential, as the FAO claims. The letter notes that dietary guidelines designed using sustainability criteria recommend significantly lower meat and dairy consumption.

Solutions like the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet were ignored, according to the letter, which suggests that the FAO “systemically underestimates the opportunities of NRDs through a number of methodological errors”. This includes assuming a higher value for meat intake than the lower range represented in NRDs, double-counting meat emissions until 2050, mixing different baseline years, including fruit, vegetable and nut emissions (which the academics say are unrelated to substituting meat and dairy in diets, and assuming very high emission intensities for an increase in plant-based products.

The FAO arrived at its conclusions by “conflating sustainable dietary change with NRDs and using opaque and incorrect methods with incomplete data”, the letter states. “The result is likely to give a false impression that the emissions mitigation potential of reduced meat consumption is limited, and thus that intensification of livestock should be the primary, if not exclusive, aim,” it adds.

“The FAO’s errors were multiple, egregious, conceptual and all had the consequence of reducing the emissions mitigation possibilities from dietary change far below what they should be. None of the mistakes had the opposite effect,” said Hayek, who co-authored a report that measured all agrifood emissions, which the FAO incorrectly applied to livestock emissions alone. “It wasn’t just like comparing apples to oranges. It was like comparing really small apples to really big oranges,” he explained.

The FAO has a lot to answer for among heavy criticism

The letter comes a month after Behrens and Hayek wrote a joint letter with fellow academics criticising the FAO’s failure to recommend a reduction in meat consumption. “By failing to recognise the need to reduce the production and consumption of animal-sourced foods, the FAO misses a central element of a climate-friendly food system,” said lead author and Stockholm Environment Institute researcher Cleo Verkuijl. “It’s like publishing a 1.5°C roadmap for the energy sector that ignores the need to scale back fossil fuels.”

Behrens and Hayek were also involved in a global survey of 210 climate and food experts in March, who agreed that meat and dairy production needs to be cut substantially and rapidly. The survey suggested that livestock emissions must peak by next year, and be slashed by 60% by 2030 – 92% said doing so is key to limiting temperature rises to 2°C. Meanwhile, 85% stated that it’s important for human diets to shift to plant-based alternatives, which are considered the ‘best available food’ and should be given preference in climate (83%), agriculture (78%) and food purchasing policies (82%).

Last year, the FAO was the subject of an investigation revealing that it succumbed to pressure from the livestock lobby and censored its own officials’ reporting on animal agriculture’s methane emissions. “Even if livestock contributes 18% to climate change, the FAO shall not say that,” its livestock analysis head recalled being told by a senior in 2009. “It’s not in the interest of the FAO to highlight environmental impacts.”

And as mentioned above, the UN organisation reduced its estimate of the livestock industry’s climate impact in its latest report, which is the target of Behrens and Hayek’s criticism. While the sector was said to be responsible for 18% of overall emissions in 2006, this was changed to 14.5% in 2013, and is now 11.2% – despite global meat production rising by 39% from 2000 to 2014, agriculture emissions jumping by 14%, and other studies calculating livestock’s emissions agree at 20% or between 16.5-28.1%.

It seems the FAO has quite a lot to answer for. “As a knowledge-based organisation, FAO is fully committed to ensuring accuracy and integrity in scientific publications, especially given the significant implications for policymaking and public understanding,” a spokesperson for the organisation told the Guardian.

“We would like to assure you that the report in question has undergone a rigorous review process with both an internal and external double-blind peer review to ensure that the research meets the highest standards of quality and accuracy, and that potential biases are minimised. FAO will look into the issues raised by the academics and undertake a technical exchange of views with them.”