6 Mins Read

Lower sugar, lower emissions, lower waste – it’s a chocolate bar that can do it all, and uses it all. Can this sustainable indulgence save chocolate and the world?

Switzerland is renowned as one of the chocolate capitals of the world, whether we’re talking commodity, high-end, or a bit of both. So as cocoa crops and chocolate bars face an uncertain and increasingly volatile future, it should perhaps come as no surprise that the home of Nestlé, Lindt, Toblerone, Cailler and Frey is hoping to lead the fight for the industry’s survival.

It may sound like an exaggeration – but just look at the data. Thanks to disappointing harvests, cocoa prices have been on a wild ride over the last year, reaching all-time highs in recent months. In April, a ton of cocoa was priced at over $12,000 – for context, it was under $2,500 in January 2023.

Crop failures have driven a third consecutive year of cocoa shortages, and it’s those on the farm who are the hardest hit – large chocolate companies continue to line their pockets. While investment in the sector is dwindling, the climate crisis is a major culprit. Scientists are warning that a third of cocoa trees could die out by 2050, just as chocolate production continues to decimate the planet.

Dark chocolate is the second-most polluting food (behind only beef), thanks in large part to the widespread use of palm oil, a major source of deforestation. While farmers in Ivory Coast, the largest cocoa producer, are truly feeling the heat, more than 85% of the forest has been lost since 1960. This is why the EU and the UK are introducing bans on importing deforestation-linked cocoa – although these come with their own strings attached.

Suffice it to say: chocolate and our sweet tooth are in trouble. Some startups are developing cocoa-free and lab-grown, with future chocolate bars featuring “less cocoa or none at all”, as one writer puts it. But researchers at ETH Zurich, the public research university in the Swiss capital, are going the opposite route, making chocolate that contains all of the cocoa fruit, and just the cocoa fruit.

It’s part of an Innosuisse (the state innovation agency) project, where a research team led by ETH Zurich professor Erich Windhab worked in tandem with cacao fruit startup Koa and Swiss chocolate manufacturer Felchlin to develop a recipe for the novel chocolate.

Finetuning a game-changing cocoa gel

Consider the honeydew melon. It has a large outer shell, and, when you cut it open, you encounter the flesh, as well as the seeds and pulp. Cacao fruit is similar.

Cocoa beans are the seeds of this fruit, but very little of the plant actually ends up in the chocolate bars we buy. It’s why you see cocoa percentages on packaging, as they’re mixed with some kind of sugar, fat and other flavourings.

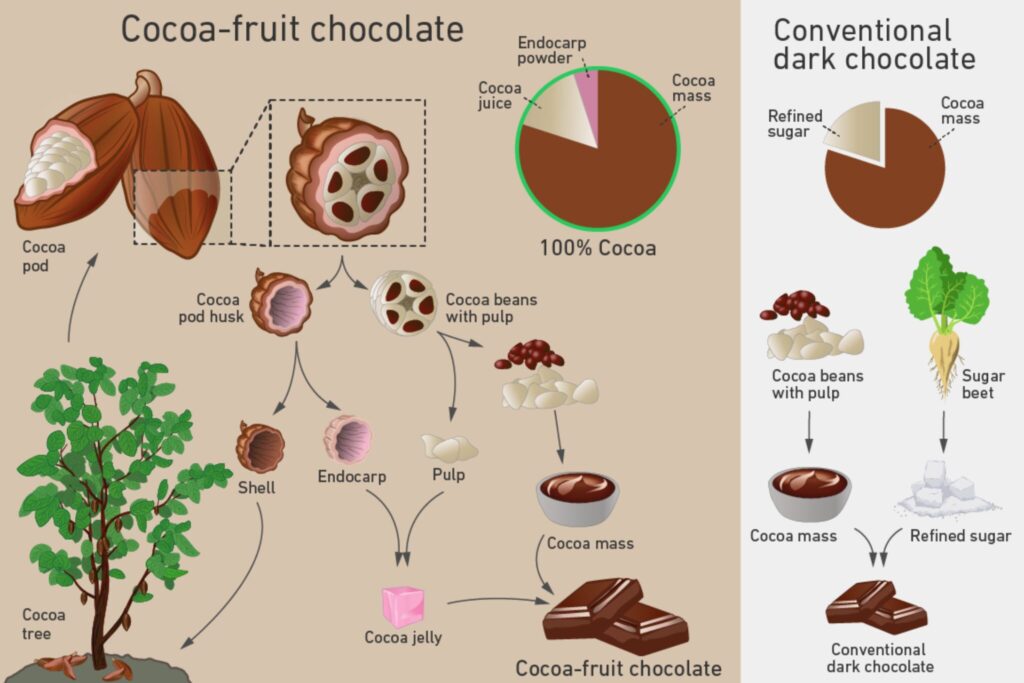

But ETH Zurich researchers have managed to tap into the flesh as well as the outer shell – or the endocarp – for its ‘cocoa-fruit chocolate’. This is important because they represent 70-80% of the fruit, and are usually discarded, making it one of the world’s most wasted fruits. Making use of these parts of the plant can open up a new income stream for farmers, revive degraded landscapes, and produce clean energy too.

It’s something startups like Pacha de Cacao, Cabosse Naturals (owned by Barry Callebaut), Blue Stripes and CaPao are already harnessing. However, many of these applications rely on cacao fruit as a byproduct – the team at ETH Zurich is treating it as an ingredient in its own right. This also helps remove the reliance on other industries – like palm oil and sugar – to create end products.

Here’s how they replace everything else to make it an all-cocoa bar. They take the endocarp, dry it, and turn it into a fine powder. This is then mixed with part of the pulp and heated to form a cocoa gel, which is extremely sweet and can replace the sugar used in conventional chocolate. The cocoa mass, meanwhile, is made from the beans – so the only thing left over is part of the thin outer husk, which is traditionally used as fuel or composting material.

While that might sound simple in theory, there was a lot of back-and-forth to find just the right recipe, with various tests assessing the texture of different compositions in the lab. Too much cocoa gel? It’s a clumpy chocolate. Too little? Not sweet enough. Finding the balance between sweetness and texture was hard, something that isn’t an issue when you just use powdered sugar.

Finally, though, they settled on a maximum gel ratio of 20%, which gives you the same amount of sweetness as a bar with 5-10% powdered sugar content. This is still much below the 30-40% threshold of regular dark chocolate, but the perceived sweetness was still palatable to taste testers from the Bern University of Applied Sciences, who tried chocolates weighing 5g each. They contained varying amounts of powdered sugar or cocoa gel.

“This allowed us to empirically determine the sweetness of our recipe as expressed in the equivalent amount of powdered sugar,” said Kim Mishra, lead author of a study based on the research, and R&D lead at plant-based meat pioneer Planted.

Dual benefits of sustainability and health carry mass appeal

Mishra and his team are excited about the health and environmental benefits of their creation. They carried out a life cycle analysis comparing conventional chocolate to their process both at lab-scale and commercial levels, revealing that their cocoa-fruit chocolate would have a lower climate footprint – in terms of global warming potential, and land and water use – if produced at scale.

The nutritional factor is another plus. As new players come up with ways to reduce sugar – either by using novel sweet proteins or by turning it into dietary fibre – the ETH Zurich chocolate boasts a higher fibre content (15g per 100g) compared to average European dark chocolate (12g), thanks to the use of the cocoa gel as a sweetener.

This translates to a 20% increase in fibre, as well as a 30% decrease in saturated fat, at a time when gut health is all the rage. “Fibre is valuable from a physiological perspective because it naturally regulates intestinal activity and prevents blood sugar levels from rising too rapidly when consuming chocolate,” said Mishra.

“Saturated fat can also pose a health risk when too much is consumed. There’s a relationship between increased consumption of saturated fats and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases,” he added.

He argued that small-scale farmers can diversify their offerings and increase incomes if the whole cocoa fruit can be marketed for chocolate production. “Farmers can not only sell the beans, but also dry out the juice from the pulp and the endocarp, grind it into powder and sell that as well,” he said. “This would allow them to generate income from three value-creation streams. And more value creation for the cocoa fruit makes it more sustainable.”

But it may be a while before you see cocoa-fruit chocolate in your local supermarket. “Although we’ve shown that our chocolate is attractive and has a comparable sensory experience to normal chocolate, the entire value creation chain will need to be adapted, starting with the cocoa farmers, who will require drying facilities,” said Mishra.

To that end, ETH Zurich has filed for a patent for its chocolate recipe. “Cocoa-fruit chocolate can only be produced and sold on a large scale by chocolate producers once enough powder is produced by food processing companies.” You can’t help but think that its partnership with Koa and Felchlin will only continue to serve this purpose. And who knows, maybe your Lindor balls will be filled with cocoa gel soon.