Nutri-Score and Eco-Labels: Is Carbon & Nutrition Labelling the Future of Food Packaging?

7 Mins Read

Consumers are more focused on personal and planetary health than ever before, governments are clamping down on greenwashing, and businesses are offering services to cut climate impacts and provide better labelling – are labels like Nutri-Score and Eco-score the future of food packaging?

Two weeks ago, Oatly launched a new campaign challenging the dairy industry to showcase its climate footprint. While the company itself has been doing this for a few years now, this felt a little different. It’s one of the world’s largest oat milk companies directly calling out the industry it hopes to replace – and it comes at a time of reckoning for the livestock industry.

Recent investigations have shown how departments of the UN and the EU have been heavily influenced by lobbyists from the animal industry on matters including environmental sustainability and caged farming, respectively. The former is striking, given that officials were pressured to water down their reporting about the effects of the livestock sector’s emissions.

And earlier this week, it emerged that food production in Brazil, the world’s largest beef exporter, accounts for 74% of its total emissions. And of these, 78% are associated with the beef industry. It comes on the back of alt-protein companies – which have long focused on the environmental superiority of their analogues – doubling down on the health aspects of their products.

What we eat is just as crucial as how it affects us and the planet – and increasingly so. It’s more important than ever for brands to be transparent on-pack about the health and climate credentials of their offerings, as evidenced by recent scientific studies and consumer surveys on product labelling and government clampdowns on greenwashing.

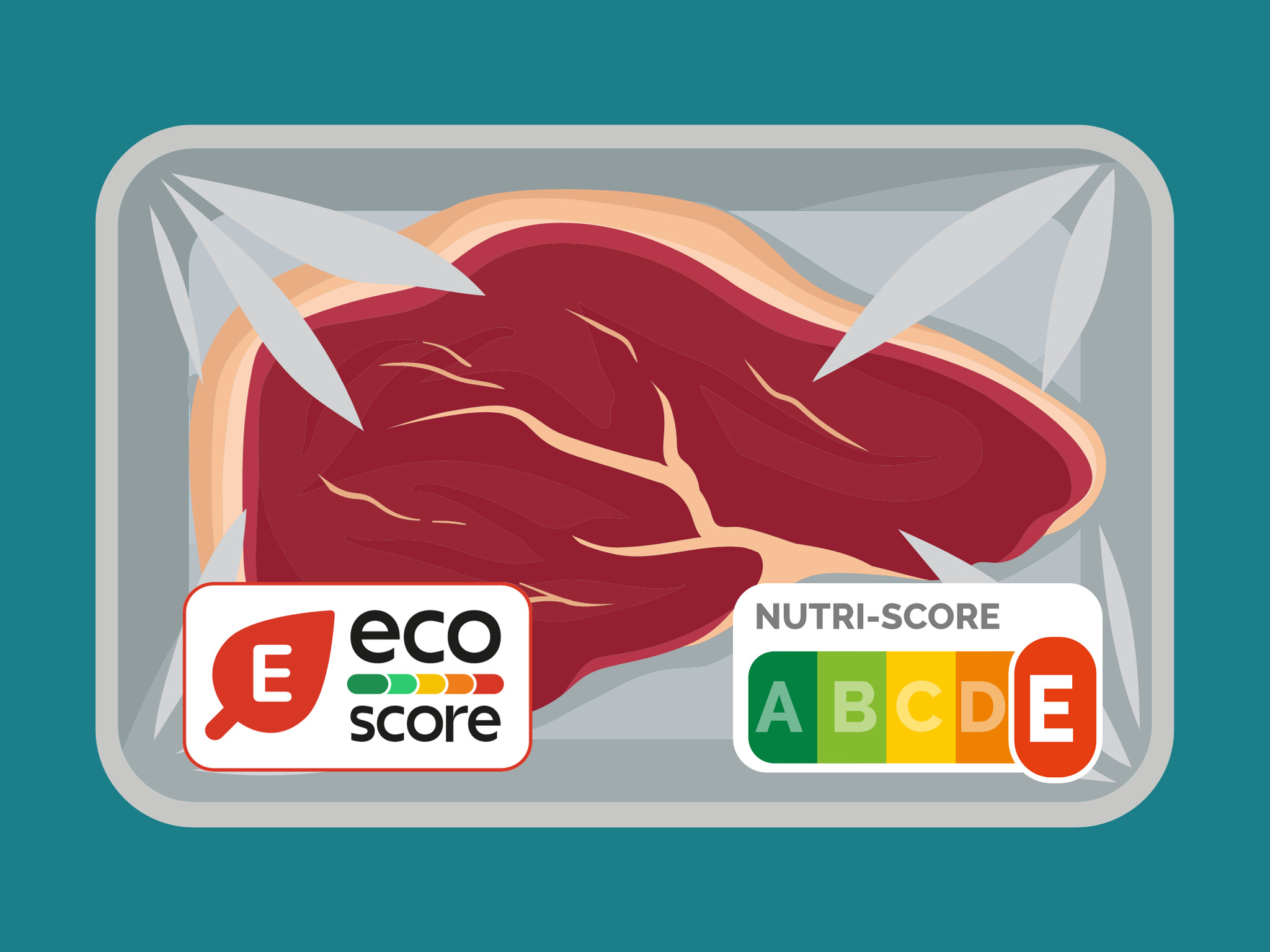

Will product labels like Nutri-Score and Eco-score be standard images on food packaging globally?

Health and sustainability are key for consumers

Let’s take meat as an example. It has a much higher carbon footprint than plant-based or cultivated alternatives, and most red and processed meat products that have a climate label on their packaging will have a low score. In Belgium, for example, a mince and pork blend at Colruyt supermarket has a red E Eco-score, the lowest possible. Similarly, in Scotland, Lidl trialled carbon labelling in 105 supermarkets in 2021, and one brand’s bacon had a C rating.

These labels have been found to influence people’s purchasing decisions, as evidenced by a peer-reviewed study of 255 Brits (a small sample size) last month. It found that 63% of consumers would be deterred from purchasing meat if it had an eco score in the red, while 52% would consider buying a meat alternative if it had a better rating. Meanwhile, 58% said they’re interested in eco-labels, but require more information – highlighting the need for more education and awareness among consumers.

In 2020, Carbon Trust carried out an analysis of three global YouGov polls totalling 10,540 participants, finding that two-thirds of respondents find carbon labelling a good idea across all countries surveyed. Support was highest in Italy (82%), France (80%) and Spain (79%). It’s because of these attitudes that industry giants like Upfield and Hilton have introduced carbon labels on their products and menus, respectively, while Unilever has committed to doing so (although it hasn’t implemented anything yet).

In terms of health labels, a French study of 1,201 adolescents aged 11-17 last year revealed that 54% had already been impacted by Nutri-Score labels during food purchases, indicating how these labels affect behaviours across demographics. This is key since peer-reviewed research last month revealed that for children and adolescents, increased plant-based food consumption alongside food fortification and supplementation where needed is recommended for sustainable and nutritionally adequate diets.

In general, health and sustainability are growing drivers of consumers’ food choices. Last year, an 8,000-person McKinsey survey covering the US, UK, France and Germany revealed that between 37-52% of people have cut their meat consumption in the last year out of health concerns, with similar or higher numbers for salt, fat, sugar and processed foods. Across the four countries, eating more fresh fruits and vegetables was the most significant change they’ve made in their diets since the pandemic.

Additionally, 60% said they value sustainable solutions – but health came out as a bigger priority, with 60% choosing it as their most important eating priority, versus a third who picked sustainability. Another survey from 2022 showed that 73% of Brits felt it was important for food and drink to have low carbon footprints, while 49% wanted to see carbon footprint labelling on products.

Consumers want food that’s better for them and the planet, and companies that can help them buy the right products will likely be winners. That’s what a study found earlier this month, stating that “food companies can enhance their sustainability efforts by prompting customers to think before nudging them into consuming more sustainable food”.

Increased government attention

There are more regulations and proposals regarding carbon and nutrition labelling, as well as greenwashing. In 2022, the EU Commission announced it would introduce “harmonised mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labelling” to “empower consumers to make informed, healthy and sustainable food choices” by the end of the year, although this has now been postponed and the legislation is yet to be implemented.

But some countries – like France, Spain and Belgium – have already adopted Nutri-Score labels, while certain brands in Portugal, Slovenia, Austria and Ukraine have voluntarily begun using these labels to better inform consumers. Food products in the UK also have a nutrition label designed by the Food Standards Agency.

Meanwhile, France and Denmark are set to introduce environmental labelling schemes in 2024. There have been calls for a similar plan in the UK too. These moves signal a wider effort to curb greenwashing across product categories. The UK’s new Green Claims Code lays out a six-point checklist to help businesses make credible environmental claims.

The EU, meanwhile, finalised a new law to effectively ban greenwashing last month, banning terms like ‘carbon-neutral’ and ‘eco-friendly’ from product labels, unless businesses can provide “proof of recognised excellent environmental performance relevant to the claim”. One of its proposed sister laws, the Green Claims Directive, mandates businesses to assess and meet new minimum “substantiation requirements” for sustainability claims – but progress on this has halted.

“Generic environmental claims are popping up everywhere, from food to textiles. Consumers end up lost in a jungle of green claims with no clue about which ones are trustworthy,” said Ursula Pachl, deputy director of consumer advocacy group BEUC.

She added: “Consumers have a crucial role to play in the green transition, so it’s good news they will have more information to make sustainable choices when buying food, new clothes or home appliances. The new EU rules will enable consumers to navigate through a sea of green claims and choose durable products that live up to expectations.”

Startups and data solutions creating better labels

A bunch of businesses and organisations are helping businesses measure their eco impacts and put climate and nutrition labels on their products. UK food regulatory consultants Ashbury recently conducted research to gauge what these labels could look like, and used AI-generated images to illustrate the results. Products like beef, milk, cheese and dark chocolate all had high footprints, while items like tea had low scores.

In 2021, British startup Provenance launched its Provenance Framework, an open-source rulebook listing the criteria companies need to fulfil to make a true environmental claim, and avoid greenwashing and misleading consumers. And Agribalyse, a French life-cycle assessment database for food and agriculture, provides environmental reference data on over 2,500 products consumed in France (including imported foods).

There’s also the True Animal Protein Price coalition, which is lobbying governments to reflect the true climate cost of these products and increase the VAT on meat to offset the tax on fresh produce. Meanwhile, startups like My Emissions, Planet FWD, Foodsteps, Reewild and Klimato all help food businesses reduce their emissions and better label their products.

Speaking on the Investing in Regenerative Agriculture and Food podcast, Tina Owens, a regenerative agriculture consultant, highlighted how only 1% of nutrition data is tracked on food labels, explaining that this is a huge opportunity for brands. ”If we know 1% of nutrition, we’re not even at the rotary phone stage of nutrition. We’re at the telegraph stage,” she explained. “And yet, we as consumers know to seek those things out for purchasing. And so, the bare minimum… is what we’re after – we’re after this foundational step.”