7 Mins Read

The SEC has watered down and walked back on its proposed rules for mandatory corporate disclosures of scope 3 emissions – here’s why, and what that means.

As November 5 gets closer, we’re seeing more and more landmark policy decisions in the US with enormous impact on companies, consumers and the climate.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has already delayed a rule that would limit the greenhouse gas emissions of gas-fired power plants, and pulled back regulations that would have mandated automakers to make EVs their main business. Meanwhile, the Chevron Deference doctrine will likely be reversed soon, with significant implications for climate legislation.

Now, the US’s corporate regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), has published its long-awaited rules for corporate carbon disclosures – and they’re not what they were originally promised to be. A two-year-long campaign by corporations, the agriculture lobby, anti-climate conservatives, and right-wing groups pushed back aggressively on the SEC’s proposed rules, resulting in over 24,000 comments submitted – the most the watchdog has ever received.

But how did we get here, and what does this mean? Here’s a breakdown of the new SEC rules on corporate carbon disclosure, and their implications in a climate election year.

What were the proposed rules?

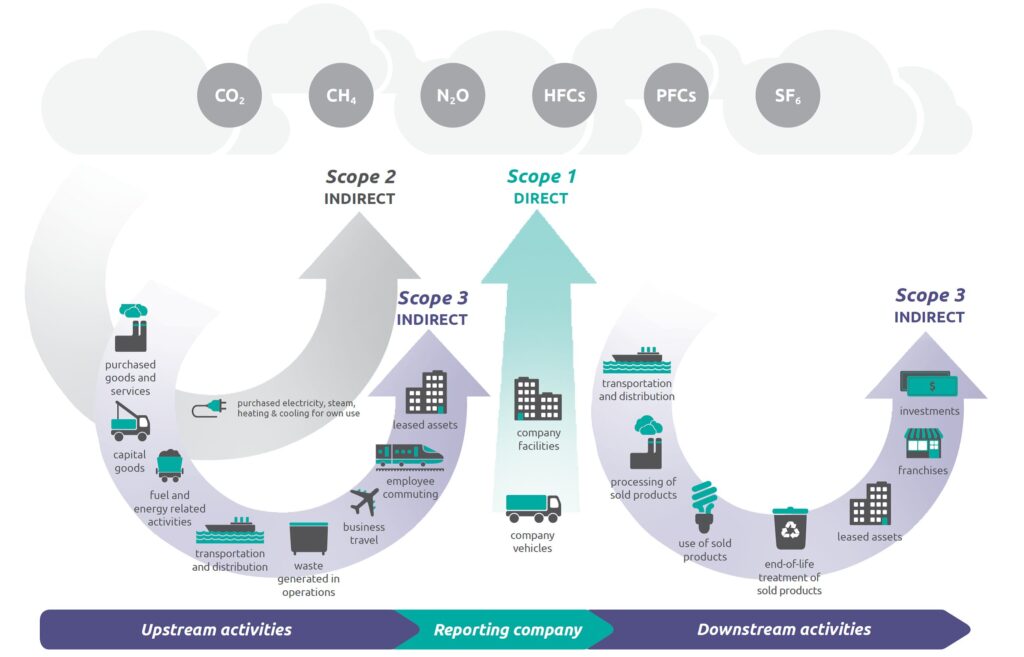

In March 2022, the SEC proposed a climate disclosure rule that would mandate companies to report their greenhouse gas emissions. This included Scope 1 emissions, which come from direct emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to make products, drive vehicles or heat buildings; Scope 2 emissions, which refer to indirect emissions that come from purchased electricity; as well as Scope 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions that stem from across a company’s supply chain and the use of its products by consumers.

Apart from the material risks, the SEC’s rules would also require companies to disclose the financial impact of climate risks on the business. Crucially, though, the proposed regulations noted that companies would only need to disclose Scope 3 emissions if they considered these ‘material’ enough – unlike Scopes 1 and 2, which would be mandatory – or if they had a specific GHG reduction target that included Scope 3 emissions.

The SEC argued that this was because Scope 3 emissions result from the activities of a third party, which means collecting information and calculating emissions would be potentially more difficult to measure than Scopes 1 and 2. While the regulator recognised the importance of Scope 3 disclosures to investors, it said a balance was needed between “the importance of Scope 3 emissions” and “the potential relative difficulty in data collection and measurement”.

What did the public comments say?

In the comments on the SEC’s proposed regulations, there were some calls for the disclosure of Scope 3 emissions to be mandated. Some companies said they already use Scope 3 emissions to make investment decisions, while others said they have been disclosing this data and expressed support for the rule. Another argument was that requiring companies to disclose Scope 3 emissions might prevent them from outsourcing to third-party facilities that would count as Scopes 1 or 2, which could lower their transition risk exposure and facilitate greenwashing.

Its opponents, however, questioned the SEC’s authority to require disclosures of emissions that “may come from non-public companies” in businesses’ value chains. There were concerns raised about the relevance of Scope 3 emissions to investors, with some finding this data unreliable and others worried about the costs of gathering and validating information. Many supported the mandatory disclosure of Scopes 1 and 2, but not 3, despite the latter accounting for 70% of many corporations’ carbon footprint.

Meanwhile, many commenters were against mandatory reporting of greenhouse gas emissions altogether (including Scopes 1 and 2), arguing that it would require companies to disclose the information even if they haven’t determined climate risks to be material, suggesting that this is why a requirement may not be useful for investor decisions. Others stated that companies that make up about 85-90% of the US’s emissions already disclose this data as part of the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, so the proposed rules are unnecessary and the resulting data consuming to investors.

What do the EPA’s final climate disclosure rules include?

These comments – and the pushback from corporate interest and anti-climate groups – had a lasting impact on the EPA’s decision-making, with the rules now removing any requirement for Scope 3 emissions reporting. Equally as important, the EPA has also walked back its guidance mandating companies to disclose Scopes 1 and 2 data – the 3-2 vote means that companies only need to report their GHG emissions if they consider them material enough.

There was a considerable list of modifications the SEC made following the public comments. These include:

- Eliminating the requirement to disclose Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, only mandating it for companies that have over $75M in public stocks and $100M in revenues, and even then, only if they deem the emissions to be material. Plus, they have the option to delay their disclosures.

- Consequently, exempting smaller and emerging companies (including those with less than $100M in annual revenues) from mandatory GHG emissions disclosure.

- Removing mandatory Scope 3 emissions reporting altogether.

- Eliminating the requirement to describe the climate expertise of board members.

- Removing the obligation to disclose the impact of severe weather events and other natural conditions on each line item in a company’s financial statements.

Wait, so what do companies actually need to report?

It might seem like companies don’t need to disclose much information. And while that’s true for the big bits around Scopes 1, 2 and 3, the SEC has listed out a few things that businesses need to report, including:

- Climate-related risks that have had or could have a material impact on business strategy, operations, or financial condition – and what those effects could look like.

- Disclosures around activities to mitigate or adapt to climate risks, and the financial impacts of the same.

- The costs and losses incurred by extreme weather events and natural disasters in the financial statements.

- Information about climate targets or goals that have or can have a material impact on its business, finances and operations.

- The expenditure involved in purchasing carbon offsets and renewable energy credits or certificates, if they’re used as part of a company’s climate goals, in the financial statements.

What does this all mean?

Essentially, it’s a non-mandatory rule, and it means it isn’t necessary for businesses to tell consumers about their climate impact, unless they think it’s important.

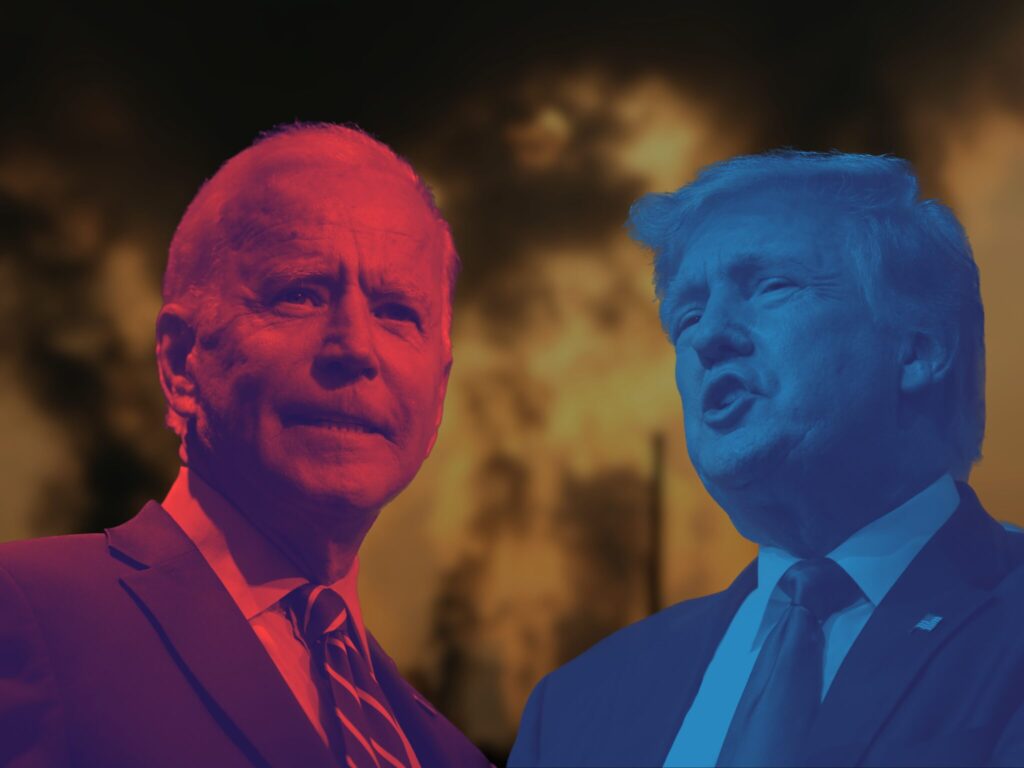

About 60% of US-based public companies will be exempt from the rules. The disclosure of climate risks to their assets will begin in 2025, with the reporting of Scope 1 and 2 emissions for eligible businesses who find them significant will start from 2026 – both years when the US could plausibly have a new (well, old) president in Donald Trump. His party has already hit back, with 10 Republican-led states suing the SEC for its watered-down rules. Some climate groups, meanwhile, are considering doing the same because it didn’t go far enough.

“The SEC has over a century of statutory and regulatory precedents that support the ability to call on companies to disclose material information. In a normal world that isn’t dominated by business-friendly courts that are packed by Trump, like the Fifth Circuit, there would be no question that this would be a rule safe from legal attack,” Clara Vondrich, senior policy counsellor at consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, told Heated.

“Now, of course, we’re living in a different time. But for the SEC to be effectively chilled in performing its core obligations by a phantom threat, by a radical judiciary, is not the way democracy is supposed to work.”

Speaking to the Guardian, Allison Herren Lee, the SEC’s former commissioner and acting chair, noted: “Under the new rule, companies will not have to disclose the bulk (or, in some cases, any) of their GHG emissions. It paves the way for greenwashing.”

It’s not a great look for the Joe Biden administration, which has been scrambling recently to reshape its climate policies to appeal to a wider range of voters ahead of November. It also puts the US behind other legislative bodies that have rallied against greenwashing and strengthened climate accountability measures for corporations.

The state of California has already passed SB 253, which mandates companies to disclose all Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, regardless of materiality. It came around the same time it passed AB 1305, which requires companies and offset providers to be more transparent in their claims and disclosures. Meanwhile, the EU is set to introduce climate disclosure rules too, including Scope 3 if they’re deemed material enough. Even China will soon begin mandating Scope 3 emissions reporting for big companies.

Polling shows that Trump is marginally ahead of Biden – and a reelection for the Republican could spell further disaster for the climate. But the latter’s recent pullbacks of his climate policies will likely not sit well with many. There’s talk that the SEC might clarify its guidance at some point, or rigorously question a company if it denies materiality. However, as Vondrich said: “We have to look at the rule as it stands today. And the rule as it stands today sucks.”