What’s In A Name: Why Does The Word Vegan Cause Such an Averse Reaction and What Does That Mean For Brands?

10 Mins Read

A host of studies over the last few years have shown that consumers don’t like the word ‘vegan’ on product labels, even if they’ll otherwise like or consume those items. So how do you disassociate vegan food from its definition?

I wonder if this has ever happened to you. You’re eating at home with your family, with a bunch of dishes and their exact vegan replicas. One of your non-vegan loved ones picks up the plant-based dish (say, an Impossible Bolognese, mistaking it for “the real thing”), eats it, and loves it (or at least doesn’t bat an eyelid).

Now, consider this. Someone instead asks you to pass that same pasta to them, but you tell them it’s vegan as you pick up the serving bowl. “Oh no no, I don’t like the vegan one,” they say, requesting you to place it back down and give them the Bolognese with the conventional beef.

I ask because this has happened to me, on multiple occasions. Maybe it was a sabzi with oil instead of ghee, or a pancake with vegan butter, or a scramble that came from plants rather than a chicken egg. People are creatures of habit, mostly hesitant to embrace change.

This is a predicament many manufacturers and restaurants have been facing when it comes to plant-based food. How do you convince a consumer to buy your product or dish with a few words on your packaging or menu? The obvious answer, of course, is by telling them it’s vegan.

But like many things, just because something seems obvious doesn’t mean it rings true. There has been a lot of discourse about labelling in plant-based food this year. I’m not talking about the use of meat- and dairy-related terms – that’s a whole other conversation – but rather the message brands are trying to promote to reach a wider consumer base.

The problem

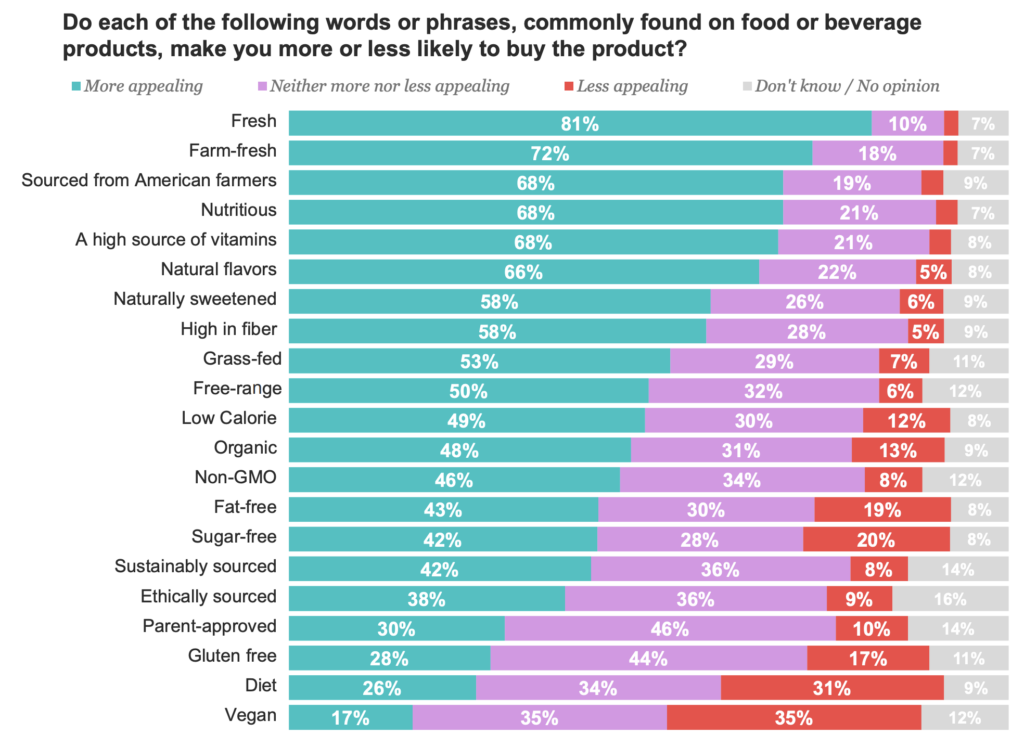

This isn’t a new conversation – it’s one marketers have been having for years, with several studies pointing to consumers’ specific aversion to the word ‘vegan’. In 2018, Morning Consult research revealed that for the 2,201 Americans surveyed, ‘vegan’ is the most unappealing descriptor for groceries, chosen by 35% (ahead of terms like ‘organic’, ‘gluten-free’ and ‘sugar-free’).

In 2019, the World Resources Institute (WRI) published research intended to help brands boost plant-based sales. Terms like ‘meat-free’, ‘vegan’, or ‘vegetarian’ were a no-go, and considered to be “healthy-restrictive”. The argument by respondents was that ‘meat-free’ means less of what meat-eaters like, ‘vegan’ represents something different from themselves, and ‘vegetarian’ means healthy but unsatisfying.

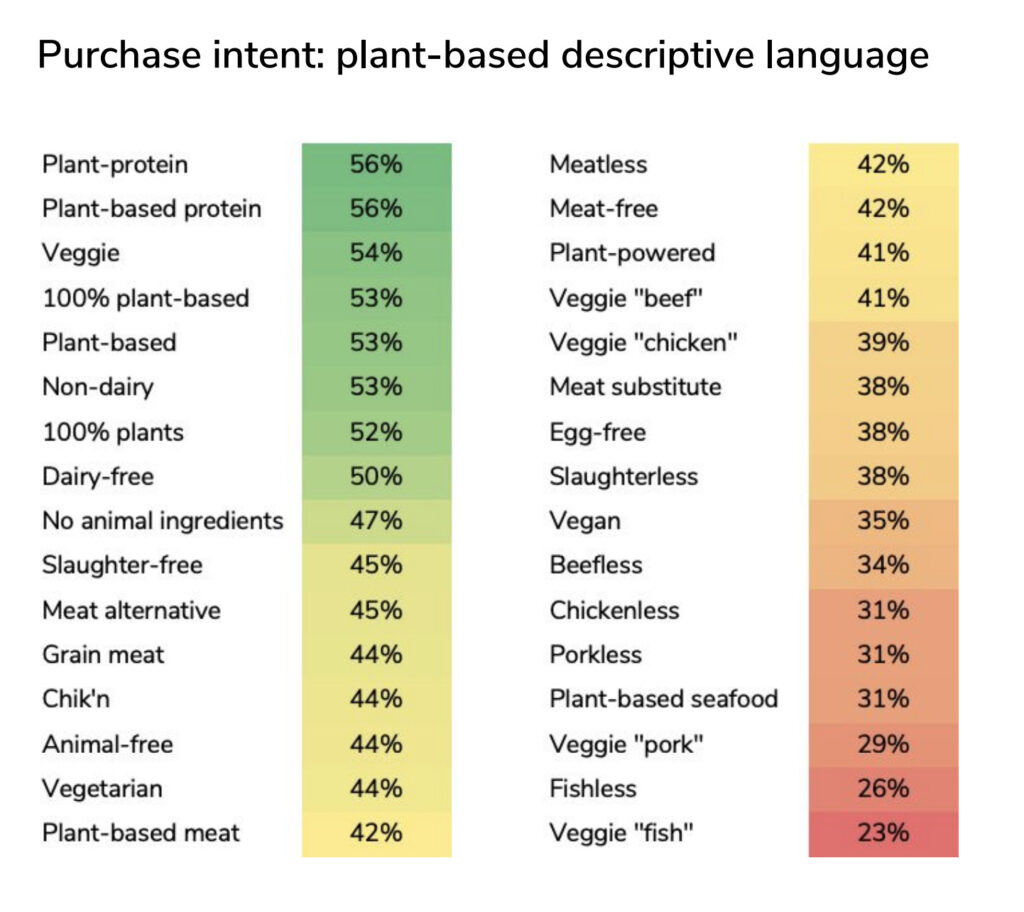

The same year, analysis by alt-protein think tank the Good Food Institute yielded similar results. Terms like ‘plant protein’, ‘plant-based protein’ (56% each), ‘veggie’ (54%), ‘100% plant-based’ and plant-based (both 53%) are much more appealing than descriptors such as ‘meatless’, ‘meat-free’ (42% each), and ‘vegan’ (35%). The latter was amongst the least effective ways to label vegan food, behind only stuff like ‘[insert animal here]-less’ and ‘plant-based seafood’.

Last year, Dutch consumer insights firm Veylinx found that – contrary to other reports – calling a hot dog ‘meatless’ works better than other terms. But like other reports, ‘vegan’ still ranks low, even behind ‘animal-free’. In fact, a ‘meatless’ label can boost demand by 16% compared to ‘vegan’.

Another study, published earlier this year in the Appetite journal, focused on menu labelling, which found that “menu items were significantly less likely to be chosen when they were labelled” as vegan or vegetarian, versus not being labelled at all. Conversely, it didn’t find that “vegetarians and vegans were more likely to choose items with meat when the labels were removed”.

The most recent study of the bunch, conducted by the University of Southern California and published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology – has made the rounds everywhere for the past few weeks, in part due to its large sample size of 7,341 Americans. The researchers used gift baskets as a gauge for which labels work, and which don’t. Participants chose between a vegan and non-vegan food basket, with the former being labelled in five different ways.

Only 20% chose the ‘vegan’ gift basket over the meat and dairy one, while 27% picked it when labelled ‘plant-based’. However, describing them with impactful attributes represented a significant upturn: when marked as ‘healthy’, 42% went with the vegan basket, while 43% did so for those tagged as ‘sustainable’ or 44% when labelled as both ‘healthy’ and ‘sustainable’.

“Our study described every single item that was in the food basket, but we just didn’t call it vegan,” study co-author Wändi Bruine de Bruin told the Washington Post. The research concluded: “This labelling effect was consistent across socio-demographics groups but was stronger among self-proclaimed red-meat eaters. Labels provide a low-cost intervention for promoting healthy and sustainable food choices.”

This is perhaps why companies like the aforementioned Impossible Foods are moving away from terms like ‘vegan’ – there has been a noted push towards using the term ‘meat from plants’ in the brand’s communications of late. (California’s Eat Just similarly uses ‘made from plants’ to describe its Just Egg products.) But why do people have such a problem with the term ‘vegan’, despite not necessarily disliking the products themselves?

The reason

Among the multifaceted reasons behind people’s aversion to ‘vegan’ labelling, one is an inherent view that meat-eating is entrenched deep into their culture. In 2021, Ipsos conducted a 1,018-person poll that revealed 59% of US citizens believed eating meat is the American way of life, and 52% felt that people advocating for reduced consumption are trying to control what the public eats.

People have been inadvertently eating vegan all their lives – an aglio e olio is typically plant-based, just as an Oreo or Lotus Biscoff biscuit is – but they don’t like the word. Paul Shapiro, co-founder and CEO of fungi protein startup The Better Meat Co., calls ‘vegan’ the “product label which shall not be named”. He writes: “Part of the problem may just be that, for whatever reason, a lot of people simply think “vegan” food won’t taste good. After all, it’s well-established that taste is by far the biggest motivator of food purchasing.”

Some would argue that the fact that so many vegan alternatives to meat and dairy exist is counter to the lifestyle’s point – isn’t it all about eschewing those very products? But it seems consumers find it hard to detach what they eat with how it affects the planet. One study has shown how vegan diets are associated with 75% fewer emissions, water pollution and land use than meat-rich diets – a similar percentage (74%) of Americans don’t think meat has any impact on climate change, a figure that climbs to 78% for dairy.

For many people, veganism still hasn’t shed its early reputation of bland rabbit food, or one that has poor analogues trying to mimic animal products, despite companies making ever more realistic versions. There’s a sense of compromise (in terms of ingredients and flavour), deprivation (regarding the satisfaction provided by food) and restriction (since you’re giving up a lot of things).

“If your freedom is restricted, a motivational drive emerges,” psychology professor Jason Siegel told National Geographic. He explained the phenomenon of reactance – or the mental pushback resulting from choice restriction. To avoid triggering this, he noted that framing change as a choice instead of an order is much more helpful – something that could be applied to what many find are extremist tendencies in the vegan movement. “If I say: ‘Please consider this, it’s up to you,'” he explained, “that’s often better than: ‘You must do this or you’re a terrible person.’”

It’s this rhetoric that Impossible CEO Peter McGuinness is hoping to banish, describing early messaging around alt-meat as unhelpful: “There was a wokeness to it, there was a bicoastalness to it, there was an academia to it… and there was an elitism to it – and that pissed most of America off,” he said at an Adweek X conference. Echoing Siegel, he added: “The way to get meat-eaters to actually buy your product is not to piss them off, vilify them, insult them and judge them,” he said. “We need to go from insulting to inviting, which is a hell of a journey.”

Britty Mann, founder of the US non-profit Planted Society, which helps restaurants add vegan dishes to menus, told Green Queen that it’s scary for businesses to take risks by adding plant-based options. “Chefs express the same fears that we hear from friends and family: ‘It’s too expensive, I don’t have time, it’s not going to stick, I’ll lose the respect of people I like, and if it’s not broke, why fix it?’”

The solution

So, where do brands go from here? Highlighting attributes relating to health is often much more successful than pointing out the climate or animal welfare aspects of plant-based products. This is a shift we’re already seeing in the space, from the likes of Beyond Meat and Impossible in the US to THIS in the UK and Dreamfarm in Italy.

Detaching the rampant misinformation is also key – for years, meat industry interest groups have been targeting vegan companies and their products as overprocessed junk food, and they’ve been successful in alienating a significant amount of consumers. This is something Beyond Meat looked to tackle with one of its ad campaigns this year, putting the focus on its steak’s cleaner-label ingredient list. Soon after, the brand then pivoted to a health focus in its marketing campaigns.

There’s something to be said about advocating for meat reduction over outright elimination – realistically, the world may never go fully vegan, but cutting back on animal products is a more pragmatic approach that presents tremendous environmental benefits. For example, if you just replace just half of your meat and dairy intake with plant-based alternatives, it will reduce emissions by 31%, halt deforestation, and double the overall climate benefits.

Blended meat companies – which mix animal proteins with plant-based ingredients in varying proportions – are the biggest proponents of this idea. Andrew Arentowicz, founder and CEO of 50/50 Foods, summed it up in an interview with Green Queen in October. “Asking everyone to turn into a vegetarian is an impossible goal. At least today it is, and we need bold solutions to big problems today,” he said. “I’m too practical to let perfect be the enemy of the good. Cutting beef consumption in half will save lots of animals, so we’re technically on the same team.”

For alt-dairy companies, honing in on the base ingredient is a great way to go, the way brands like Alpro have done. Bar one (its This Is Not M*lk range), Alpro’s products don’t bother with terms like ‘drink’, ‘yoghurt’, ‘mylk’, etc. – instead, you see a tetra pack with a giant ‘Oat’ or ‘Coconut’ with health and flavour descriptors, with Alpro trusting consumers to know they’re looking at a milk alternative.

This is harder for plant-based meat, of course. People want ‘almond milk’, but they don’t necessarily want a ‘pea protein burger’, irrespective of the fact that they like it – pushing them to make the choice to buy the product involves detaching from words like ‘vegan’ or unappetising phrases, such as the ones we saw above (‘fishless’, etc.).

For these businesses, it’s key to note that vegans aren’t their key demographic – that’s flexitarians and meat-eaters. “We’re trying to reach meat eaters – not vegans, vegetarians or those already eating sustainable diets. That’s why we focus on making products that appeal to actual meat eaters,” an Impossible spokesperson told Green Queen earlier this month. “Our goal is not to compete with fruits, vegetables, and other whole foods, but to offer meat eaters products that are better for them and the planet.”

In terms of foodservice, a ProVeg International report suggested listing plant-based items alongside other options, but on top is an effective motivator. Instead of using the product name as the label, it recommended restaurants to use subtle, easily identifiable labels (like pictograms) to “minimise the deterrent effect that vegan-identifying denominations can have on mainstream consumers”.

Emphasising flavour attributes as well as provenance (i.e. referring to the birthplace of a dish or its culinary history) can go a long way towards encouraging consumption, in addition to highlighting the product’s appearance and texture according to WRI research. Meanwhile, brand consultancy Fuze released a strategy guide for restaurants, which suggested using discreet symbols to mark vegan or vegetarian dishes, as those labels are often seen as lifestyles: “Trust that your conscious customers will spot these options.”

There are tons of opinions – many contradictory – on best practices when it comes to plant-based marketing and branding, but one consistent viewpoint is that many people, for better or worse, actively dislike the word ‘vegan’ when it comes to labelling. Do vegan brands need to move away from their very identity to resonate with more customers and reach mass appeal?