Meat Kills: How Cigarette-Style Warnings Could Help Cut the UK’s Meat Consumption

6 Mins Read

Cigarette-style warnings about the impact of climate change on food can cut meat consumption, according to a study by Durham University. Researchers found that adding pictorial climate warning labels deterred Brits from choosing meat dishes by 7.4 percentage points, and participants aren’t be opposed to policies mandating such labels.

‘Smoking kills.’ It’s a ubiquitous label found on cigarette and tobacco packaging, a mandatory label designed to deter people from smoking, without actually banning the act. Can governments do the same for meat consumption, which also kills?

That’s what researchers are Durham University ventured to find out in a UK-wide study published last month in the peer-reviewed journal Appetite. Surveying 1,001 Brits, the study aimed to find whether providing pictorial labels about the impact of meat-eating on climate change, health and pandemics on menus can influence people’s decisions to opt for a meat dish.

Meat consumption has been linked to increased risks of obesity, heart disease and certain types of cancer, while the industry has been found to be taking inadequate steps to prevent future zootonic pandemics. Meanwhile, meat’s impact on climate change has been well-documented. Reserach has shown that vegan diets can reduce emissions, land use and water pollution by 75% compared to meat-rich diets, and that replacing half of our meat and dairy consumption can halt deforestation and double climate benefits.

How the packaging of cigarettes can inform climate labelling

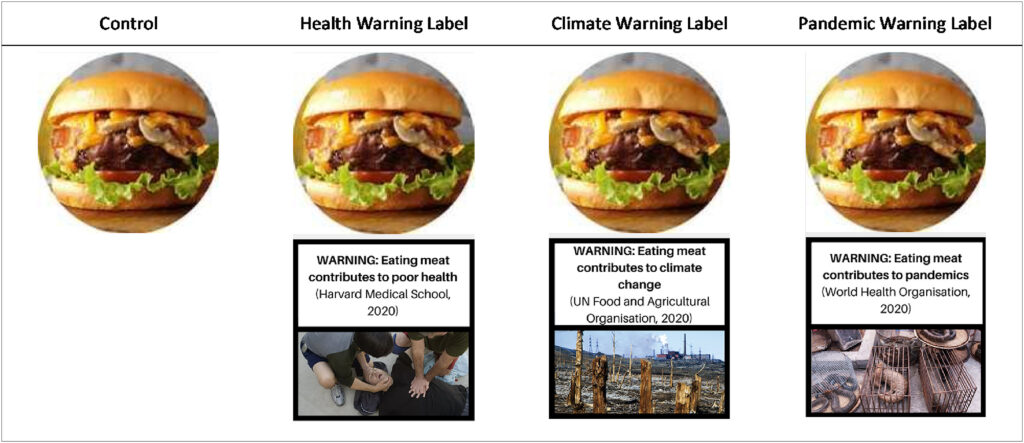

The study split participants into four groups and asked them to imagine they were in a university canteen. Each group had to choose from four hot dishes – including burgers, curries, burritos, lasagna, quiche and pasta bake – which were meat-based, fish-based, vegetarian and vegan.

For one group, the meat option came labelled with “Eating meat contributes to poor health”, accompanied by a picture of a person getting a heart attack. Another group had the label “Eating meat contributes to climate change” alongside a picture depicting deforestation, while the third group placed the meat option alongside “Eating meat contributes to pandemics”, showcasing caged animals.

The other group had no such labels surrounding the meat option – here, people chose meat 64% of the time. But when looking at the different labels, all represented a reduction in opting for meat, with the pandemic warning being the most effective, dropping the number of people choosing meat to 54% (a 10-point decline). The health warning, meanwhile, saw an 8.8-point decrease, while the climate change label affected a 7.4-point reduction.

This is in line with a recent Smart Protein survey of 750 UK consumers by ProVeg International, which found that health was the top motivating factor for Brits to reduce meat and dairy consumption, with 48% citing it. This was followed by environmental reasons (29%) and animal welfare (25%).

Similarly, a 1,000-person survey by Bryant Reserach, ProVeg and Plant Futures last month revealed that health benefits are the number one reason for Brits to eat plant-based meat (39%), followed by taste and texture (36%) and environmental benefits (17%).

The UK’s climate fight

Despite the more pronounced effect of the health labels, attitudes towards mandating such labels were flipped, with participants indicating they aren’t opposed to mandatory cigarette-style climate labels on food, but are less supportive of the health and pandemic labels.

This is key, since meat reduction needs to be a priority for the UK. According to a recent YouGov poll, 72% of its citizens classify themselves as meat-eaters. The country’s Climate Change Committee, which advises the government on net-zero goals, has recommended a 20% reduction in meat and dairy consumption by 2030. But in June, the CCC said the UK’s pace of action to reduce emissions by 68% by 2030 from a 1990 benchmark is “worryingly slow”.

Last month, ONS data revealed that meat and dairy consumption in the UK is at its lowest since records began in 1974. But the intake of fruits and vegetables has also dropped. And in September, UK prime minister Rishi Sunak U-turned on the country’s climate commitments, facing backlash after pushing back the deadline for gas and diesel car bans from 2030. Sunak said he remained committed to sticking to the UK’s net-zero goal for 2050 in a more pragmatic and realistic manner, although did not outline how he would do so.

Meanwhile, analysis by GFI Europe in August found that the UK needs to invest £390M in alternative proteins between 2025 and 2030 to avoid losing momentum to other countries.

“Reaching net zero is a priority for the nation and the planet,” said study lead Jack Hughes. “As warning labels have already been shown to reduce smoking as well as drinking of sugary drinks and alcohol, using a warning label on meat-containing products could help us achieve this if introduced as national policy.”

Hughes told TIME that adding these climate labels could actually get the UK to reach about halfway towards its target. He compared it to a similar study in 2021 in the US, which had text-only labels. That study didn’t find any significant impact, and Hughes suggested it could be due to cultural differences, but because of the addition of images and citations to the sources of information too.

A growing body of evidence

“It is not up to me to speculate or recommend how companies and restaurants use this research,” Hughes told TIME. “If these were to be implemented in the real world, what our research shows is that putting these warning labels alongside meat options when people are making decisions might be an effective way to reduce the amount of meat people are choosing.”

And there is precedent in the real world, as evidenced by the partnership between catering company Chartwells and research firm HowGood, which last week revealed that there has been an increase in student demand for climate-friendly meals in US universities after the introduction of eco labels.

Other studies that have explored the efficacy of climate labels include one from the Food Quality and Preference journal earlier this year, which found that 63% of Brits would be deterred from buying meat if it had an eco score in the red and 52% would consider buying meat alternatives if they had a better rating (though the sample size was only 255). A wider-ranging analysis by CarbonTrust, compiling data from three YouGov polls totalling over 10,000 respondents from eight countries (including the UK), revealed that two-thirds of respondents find carbon labelling a good idea.

Milica Vasiljevic, a senior author of the study, said: “We already know that eating a lot of meat, especially red and processed meat, is bad for your health and that it contributes to deaths from pollution and climate change. Adding warning labels to meat products could be one way to reduce these risks to health and the environment.”