Cell-Based Blueberries, Anyone? What is Lab-Grown Fruit, and Is It a Food Security Solution?

5 Mins Read

With climate change threatening crop growth and food security in many places, scientists are hoping to create lab-grown fruit with usually discarded parts of fruits, like apple cores and orange peels. While the process is some years away – and may not come to fruition – the potential is exciting for the future of food.

Cultivated meat has been taking up all the airwaves of late, and so have dairy proteins made from precision fermentation. Using real animal cells to create meat, or fermenting microorganisms to produce bioidentical dairy proteins are both technologies that could prove vital to the future of a food system threatened by climate change.

But it’s not just animal products that can have a cause-and-effect relationship with the environment. Fruits and vegetables, while usually at much lower levels, can also have a notable climate footprint in some regions (especially from transportation and if imported). Of equal importance is the reverse impact of the climate crisis on our produce.

Extreme weather events like floods, droughts, cold snaps and wildfires can and have damaged such crops around the world, and it’s likely to get worse if mitigation efforts aren’t made. This is where lab-grown fruit comes in.

What is lab-grown fruit?

Scientists at New Zealand’s government-backed Plant & Food Research programme are attempting to tackle this exact issue. Using plant cells to grow fruit tissue in labs could help use fewer resources, better the climate impact of fruit growing, and enhance the overall food security of the country.

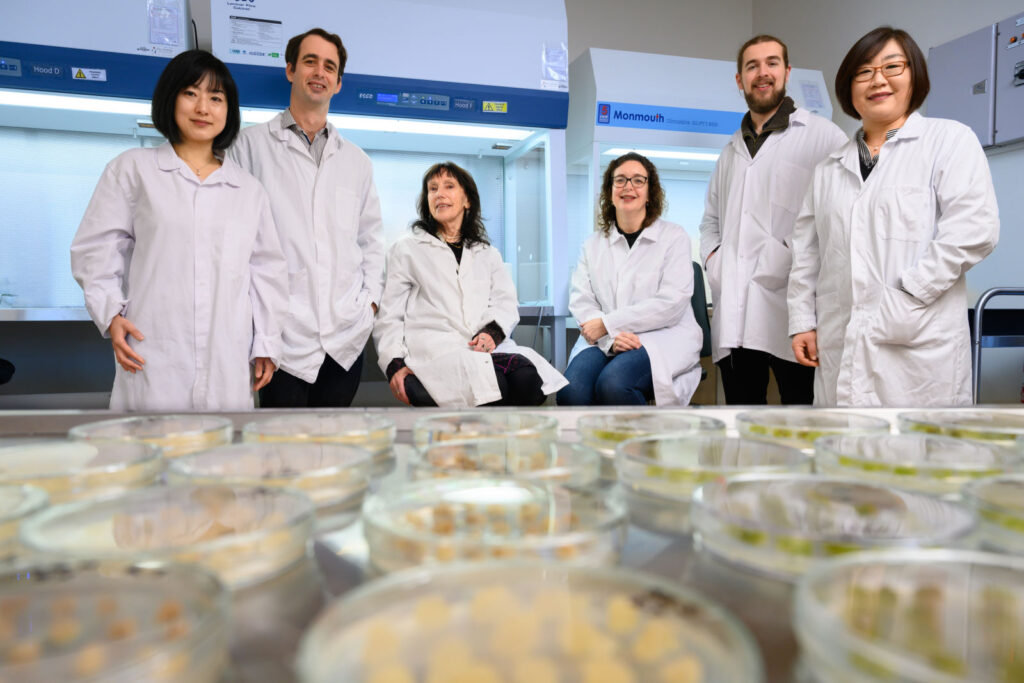

We’ve heard of cultivated meat and seafood – but cell-cultured fruits are a relative novelty. “Cellular horticulture currently has a smaller profile than cellular agriculture and aquaculture, but we believe this is a really exciting area of science where we can utilise our expertise in plant biology and food science to explore what could become a significant food production system in the future,” says Ben Schon, lead scientist for Plant & Food Research’s Food by Design programme.

It’s not the first time scientists have tried to recreate fruits from plant cells in labs. The earliest reference to growing fruit in labs comes from 1951 when pioneering researcher JP Nitsch cut a tomato flower and cultivated it in a medium of sugars and nutrients until it formed into a fully developed tomato.

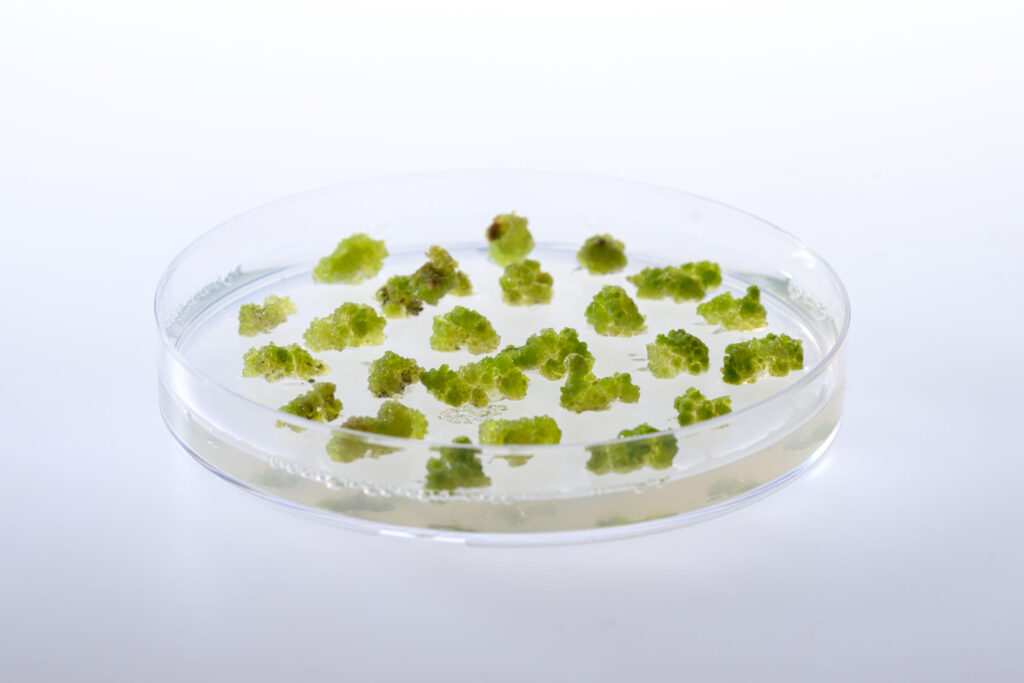

It’s certainly a concept that’s borne fruit more recently. In 2018, for example, Finnish scientists produced plant cell cultures from lingonberries, cloudberries and stoneberries, which were said to be equally nutritious and flavourful. Then, in 2021, researchers at MIT developed a way to grow plant tissues in a lab, akin to how cultivated meat is made.

Why grow fruits in labs?

The argument is that these foods could potentially have a higher nutritional value and be cheaper to produce. Much like cell-cultured meat, the New Zealand researchers say the challenge is to create fruits that are nutritious and have a familiar taste, texture and appearance.

“In order to grow a piece of food that is desirable to eat, we will need more than just a collection of cells. So we are also investigating approaches that are likely to deliver a fresh food eating experience,” explains Schon. “The aim isn’t to try and completely replicate a piece of fruit that’s grown in the traditional way, but rather create a new food with equally appealing properties.”

In February, Cyclone Gabrielle destroyed parts of the area referred to as New Zealand’s fruit bowl, Hawkes Bay, when many kiwi fruit farmers were preparing to harvest the crop. It’s just one of a number of recent and increasing climate events that are threatening food crops. Across the Pacific, peach farmers in the American South have lost two harvests to climate change. And in Italy, farmers have seen crops like kiwis, peaches, grapes and corn wither due to frosts, floods, heatwaves and hailstorms – all this year.

It’s events like these that make the argument of lab-grown fruit compelling. While Schon and his colleagues are trying to work out how viable this tech might be for future food production, they also want to provide a better understanding of fruit cell behaviour. This could help breed better varieties of fruit, which would also, in turn, benefit traditional growing methods.

The future of food?

The initial trials have used cells harvested from blueberries, apples, cherries, feijoas, peaches, nectarines and grapes. But the researchers say getting a fruit that is nutritious and flavourful could be years away – it may not be attainable at all.

And even if they came up with something viable, given this is a lab-grown food product, it will have to pass regulatory hurdles, which can be a minefield. Currently, only Singapore and the US have approved the sale of cultivated meat made this way (while some others are considering applications) – but compliance regulations will likely be different for lab-grown fruit.

If successful, though, Plant & Food Research strategy leader Samantha Baldwin says the tech could be suitable for growing fruit tissues in cities and urban areas, which would help cut costs as well as the emissions associated with transportation, according to the Guardian.

The research team is 18 months into the five-year Food by Design programme, which is funded by Plant & Food Research’s internal Growing Futures investment of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Strategic Science Investment Fund. It is also part of an agrifood tech accelerator programme by New Zealand company Sprout Agritech.

“Globally, we are seeing rapid growth in both the vertical farming, controlled environment growing as well as cell-cultured meat spaces,” says Baldwin. “It’s possible that cell-cultured plant foods could be a solution to urban population growth, with requirements for secure and safe food supply chains close to these urbanised markets.”

It may be a long way from now – but we’ve already been seeing (and eating) non-browning Arctic apples, non-bruising Innate potatoes, and antioxidant-rich pink pineapples. Why not add a little lab-grown blueberry to the mix?